The Dolmen de Alberite is, to date, the earliest megalithic passage grave in the Iberian Peninsula and the Atlantic façade.

By Nick Nutter | Updated 4 Jun 2023 | Cádiz | Places To Go |

Login to add to YOUR Favourites or Read Later

Dolmen Alberite

Sometime before 4000BC, a group of Neolithic people built the dolmen de Alberite, in the Llanos de Villamartin in Cádiz province. The ancient builders chose an area on the south side of the fertile valley of the Rio Guadalquivir, on the north-western flanks of the Sierra de Grazalema. Strictly speaking the Dolmen de Alberite is a megalithic passage grave.

Orientated to the east towards Sierra Grazelema

The Dolmen de Alberite was discovered in 1993 when agricultural workers tried to remove some of the large capstones over the passage to make ploughing of the field easier. They found three polished axes, an axe, an adze and a gouge, necklace beads made of shells, bones and green stone, together with human bones covered in ochre. The decorated human bones indicate that the passage grave was used for secondary burials of revered ancestors. In 1993, the artefacts were removed to the Archaeological Museum in Cádiz. Excavations were then carried out by a team led by J. Ramos Munez and F. Giles Pacheco from the University of Cádiz.

The Dolmen de Alberite is, to date (2022), the earliest megalithic passage grave in the Iberian Peninsula and the Atlantic façade. It has been fairly reliably dated by using the carbon 14 method on pieces of charcoal, the remnants of fires, found in the passage itself in the ante chamber. It is just one of seven passage graves and a menhir discovered in the area of the Arroyo de Alberite which, together, after all had been constructed would have made up a megalithic sacred landscape. The menhir probably predates the passage grave if the timeline for the construction of megalithic monuments follows that of other sacred landscapes in western Andalucia and the Atlantic façade. The Dolmen de Alberite is the only megalithic construction to have been excavated within this particular sacred landscape. Of the others, two were destroyed during agricultural work whilst the others are visible in the landscape as tumuli.

Artifacts in Cadiz museum

Dolmen de Alberite is a passage grave with a 23 metre long passage, 2 metres wide at the entrance widening to 2 metres at the far end. A chamber and anti-chamber have been marked out by the use of vertical stones laid across the passage. The passage itself is lined with orthostats, some of which weigh up to 8,000 kgs. That were then covered by capstones to form the roof. The entrance is monumentalised by the use of two large, vertical stones. When it was built the entire structure would have been covered with earth to form a tumuli and the exterior perimeter, about 50 metres in diameter, would have been marked by a circle of stones.

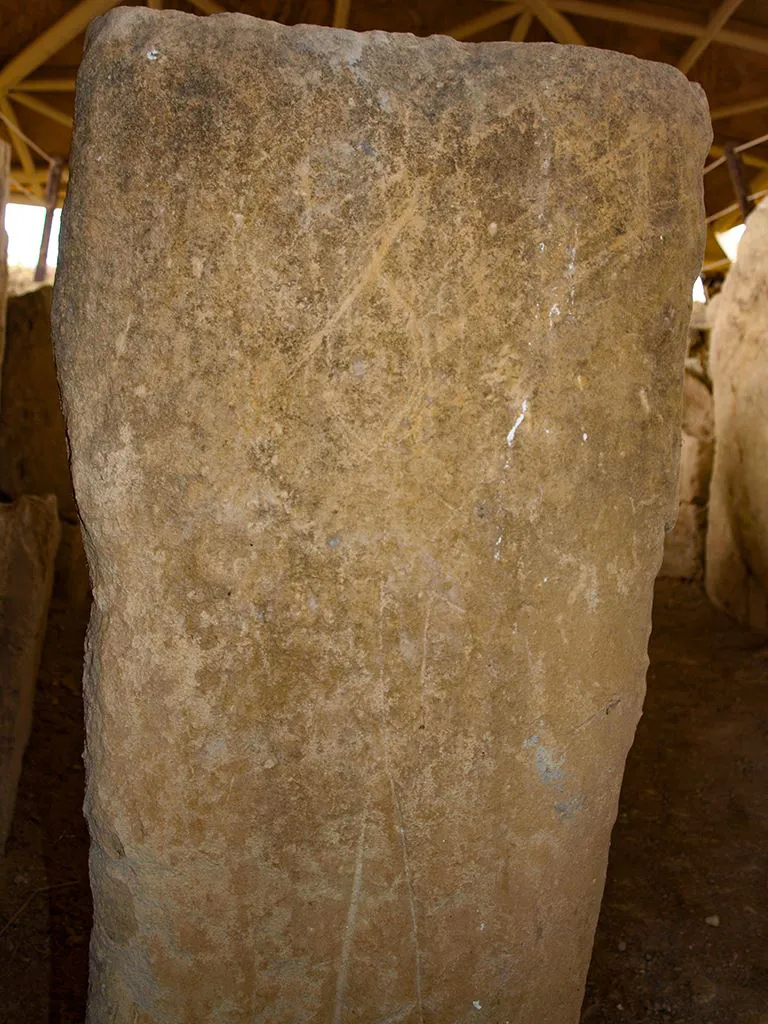

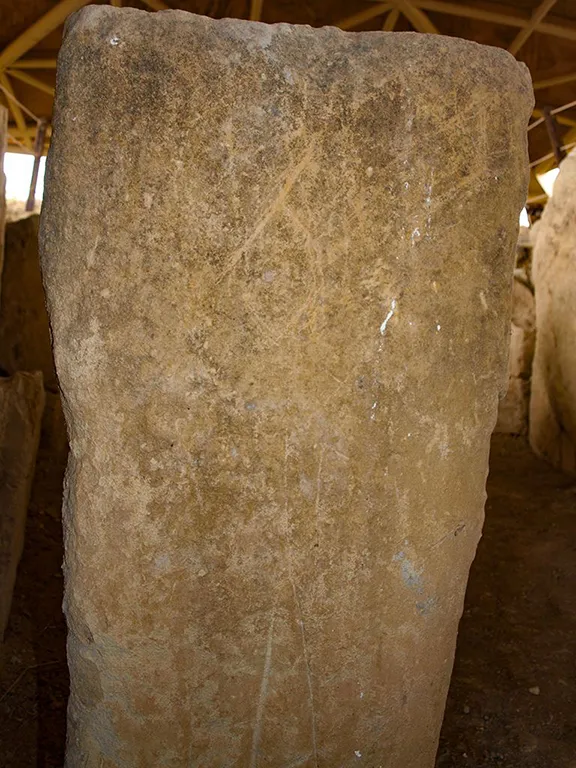

Engraved orthostat - Dolmen Alberite

Some of the orthostats were painted and engraved. The themes vary but include geometric motifs, zigzag lines, axes, knives, suns, snakes and anthropomorphs. One anthropomorph that is clearly visible on one of the vertical ‘room dividers’, depicts a warrior brandishing an axe, protecting the burial chamber beyond from human and superhuman entities. The floor of the passageway was also covered in a layer of ochre.

Dolmen Alberite - final chamber

At the head of the passageway, the final chamber was the resting place for a male and a female. This appears to be a secondary burial because the bones were de-fleshed and painted with ochre. They were carefully placed side by side with their faces facing outwards. The grave goods included 1,600 variscite, bone and shell beads, a polished adze and gouge, four flint blades and a quartz crystal some 20 cms in diameter and length. There were also some tools associated with the ochre decorations; a trowel and four crushers made from limestone.

Dolmen Alberite - final chamber

As more megalithic sites are discovered and excavated, particularly in the western part of Andalucia, in the provinces of Cádiz and Huelva, it is becoming apparent that the entire landscape was covered by megalithic tombs of various sorts; dolmens and passage graves or tombs, menhirs, some of which are re-used in later tombs and ditched enclosures. It is important to appreciate that the landscape we see today is the ‘finished landscape’ with all its features exposed.

The finished landscape began to be created about 4500 BC when the Neolithic people started to claim ownership of land by the presence of ancestors interred in megalithic tombs. The first tombs were used for a number of generations. In some areas the population felt it necessary to build a second tomb in the same area as the first and it is interesting to speculate why they did this. Was it a case of more is better, i.e. having two or more tombs increased the claim to the land? Or was it a function of the Neolithic life?

The first farmers were known to be transient, moving across the landscape as the ground in one place was exhausted. Settlements were sometimes deliberately destroyed before the population moved on to pastures new. Although the density of megalithic monuments in the south western part of Andalucia suggests a large number of human groups or tribes, it may be that there were fewer groups moving over the landscape over a period of many generations.

Whilst the ‘finished landscape’ undoubtedly had great meaning to the groups that built the last monuments, that context was not realised in its fullest form by the builders of the first monuments. In other words, the landscape, and its meaning, evolved over a period of a few thousand years influenced by new ritualistic ideas, new technology and new social norms.

It would be interesting to produce a timeline showing the ‘sacred landscape’ at different times during its evolution but, unfortunately, a massive amount of dating data has yet to be obtained and then collated. It would be as interesting to find common denominators amongst the megalithic monuments, for instance; designs of engravings, patterns on idolic plagues, styles of pottery, tools, personal decoration and weapons, that could potentially identify the separate groups responsible for their construction over the eons.

In 2004, funding was obtained to build an Interpretation Centre. Unfortunately, the builders lacked the expertise of those that built the dolmen and within a few years, part of it fell down. The centre was rebuilt, along with an adjoining bar, but the site remained closed due to lack of funding. Our visit was in 2016 and the site remains closed in 2019. The owner of the land is a café bar owner in Villamartin and it is through him that visits are arranged. There is no entrance fee, but contributions are welcome. Try ringing 615 15 97 98.

Ramos Muñoz, José & Pacheco, Francisco & Domínguez-Bella, Salvador & Fernàndez, Vicente & Pérez, Manuela & Gutiérrez López, José M. & Lazarich, María & Martínez, Cristina & Cáceres, Isabel & Felíu, María. (1999). Informe arqueológico del dolmen de Alberite (Villamartín). Anuario Arqueológico de Andalucía. 1993. 64-79.

Ramos Muñoz, José. (2012). Proyectos de estudio de Arqueología Social en la región histórica del Estrecho de Gibraltar.