Dolmen de Soto de Trigueros is a megalithic passage grave at Trigueros, Andalucia, southern Spain built between 3000 BC and 2500 BC and is one of about 200 neolithic ritual-burial sites in the province of Huelva

By Nick Nutter | Updated 4 Jun 2023 | Huelva | Places To Go |

Login to add to YOUR Favourites or Read Later

Dolmen de Soto, Trigueros

In the municipality of Trigueros, in Huelva province, is a megalithic dolmen that, according to Bueno-Ramírez, prehistorian at Alcalá de Henares University, ‘If it had been located in the United Kingdom, it would already be one of the most-visited tourist sites.’ He is referring to the Dolmen de Soto.

Strictly speaking the Dolmen de Soto is a passage grave as explained in the introduction to this series. Even then it is unusual in that the passage does not lead to a well defined chamber. This type of funerary monument is sometimes called a corridor tomb.

Entrance to Dolmen de Soto

Sometime before 3000 BC, possibly as far back as 3800 BC, Neolithic people erected a stone circle. The circle was 65 metres in diameter and utilised at least 94 stone pillars, one at least nearly 6 metres high. All the pillars were painted a striking red. One depicted hunting scenes from the period. Some of the stones had been brought to the site from 30 kilometres north of Trigueros. One of those stones weighed 21 tons.

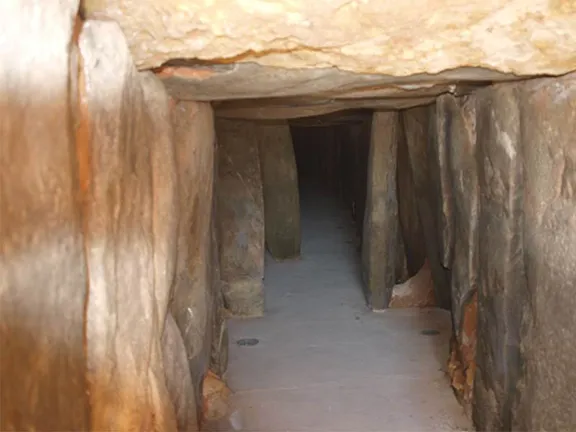

21 metre long passage of Dolmen de Soto

Whatever the stone circle was used for, solar or lunar observations, a sowing calendar, to demarcate a necropolis or some other purpose, it was dismantled between 3000 and 2500 BC. The stones were cut and used to create the Dolmen de Soto de Trigueros, the largest and most important dolmen in the province. It is just one of over 200 megalithic monuments in Huelva province.

End chamber of Dolmen de Soto

The dolmen consists of a passageway, 21.5 metres long, 2 metres wide and high at the entrance, increasing to 3 metres high and wide inside. There is no well defined chamber at the end of the passage. The 'chamber' is simply a wider, higher, extension to the passage itself sealed off at the rear end by a massive, upright, orthostat. The corridor is lined with 63 orthostats that are then covered by 30 capstones, the remnants of the original stone circle. A single frontal slab sealed the entrance. The whole was then covered in earth to form a tumulus 60 metres in diameter and 3.5 metres high.

An engraved orthostat, Dolmen de Soto

The builders then created their own art, in the form of paintings and engravings, on the orthostats.

Research using new lighting techniques was published in 2021 and many more drawings were revealed. The new drawings show armed figures. Bueno-Ramírez remarked, “There is not a single megalithic monument in Europe that has so many armed figures on its walls.” A space within the dolmen has been identified as an area where metal working took place and one figure appears to be wielding a ‘Carps Tongue’ sword, a type of weapon typical of the Late Bronze Age and of the Tartessos culture.

The dolmen was first discovered and excavated in 1922 by Hugo Obermaier, a distinguished prehistorian and anthropologist, but restoration had to wait until the 1980s. In 1922 a second, smaller, dolmen was found about 250 metres from Dolmen de Soto. This contained the remains of 18 to 20 individuals. Unfortunately, the remains disappeared soon after this dolmen was excavated.

The remains of a woman and child were found in Dolmen de Soto, beneath a stone that had an engraving upon it that was originally interpreted by Obermaier as a mother and daughter. Only a few grave goods have been recovered, some polished axe heads, flint knives, hand made pottery, a conical bone bracelet, some seashells and several beads. It is thought that the dolmen was plundered during Roman times.

Building Dolmen de Soto must have involved many hundreds of workers if only to move the large stones. They all had to be fed, which implies some sort of support group, probably the women, thereby increasing the numbers involved. The very large dolmens, such as Soto at Trigueros and Menga in Antequera, are thought to be the work of groups of people that could be viewed as tribes. The awe-inspiring construction would have served to stamp ownership on the land, reinforce ties between members of the tribe, and impress upon strangers the importance and power of the tribal leader and the tribe itself. It may well have served as a place at which to congregate at certain times of the year.

Whether a powerful tribal leader had sufficient sway over the tribe, or enough followers to ensure obedience, to organise the building of the dolmen or whether the tribe itself decided communally that it was a good idea is not known for certain.

The early Neolithic people and the hunter-gatherer Mesolithic people before them probably made major decisions collectively, there is no evidence from that time of elite burials, in fact, the archaeological evidence points towards an equalitarian society. Between 3000 BC and 2500 BC, the Neolithic population was disseminated across the landscape in family groups. Only later, from about 2000 BC in Andalucia, did populations start to coalesce into larger groups living in settlements that became fortified (a phenomenon that seems to have originated in Portugal from about 2600 BC). Large settlements, fortified or not, imply control, if only by bureaucrats controlling the food supply who, being non-producers, have to be supported by others.

It seems likely therefore that the dolmen phenomenon occurred between the time of egalitarian societies and authoritarian societies. The phenomenon may be seen as a manifestation of a growing awareness of unity born out of a need to identify ownership of an area of land to ensure the survival of the tribe. The concept of helping other related family groups, (tribes in all but name), having already been well ingrained into the psyche over many thousands of years. The need to identify ownership came with a growing Neolithic population that demanded the use of a finite resource, land suitable for agricultural purposes. Seen in this light, the use of large dolmens for collective burials over an extended period of time makes sense. The Neolithic people were creating a tribal history to reinforce their right to stamp their ownership on the tribal land.

Using similar reasoning, it can be envisaged that smaller, family, groups within the tribal lands, cooperated to build the hundreds of smaller dolmens, such as those at Pozuelo, that litter certain parts of the landscape. Each individual, small dolmen, would reinforce the ownership of the wider tribal land as well as ownership of a smaller, family plot of land. In order for this to work there had to be a method of identifying individual families and their tribe that others, from other tribes, would recognise. Did idolic plaques perform this function?

For opening times and to book a tour of Dolmen de Soto de Trigueros, click here