Fuengirola is a popular seaside resort on the Costa del Sol of Malaga province with an undeserved reputation for lager louts.

By Nick Nutter | Updated 11 Nov 2022 | Málaga | Villages |

Login to add to YOUR Favourites or Read Later

Fuengirola Bay

To many people, Fuengirola epitomises everything that is wrong with the Costa del Sol; high rise development gone mad, cheap beer, poor food, loutish behaviour from some elements of the population, a perceived crime problem and so on. However, if you delve a little deeper you will find that Fuengirola is not all it seems on the surface and certainly no longer deserves its reputation. Discover the new Fuengirola.

Fuengirola Beach

First of all the beaches. There are 7 kilometres of beach stretching from Sohail Castle in the west to Torreblanca in the east. Not quite soft sand, more a fine gravel, the beaches are well maintained and attractive. Islands of palm trees here and there, chiringuitos, most with wood barbeques for the traditional espetos; fish cooked on a skewer, sunbeds and parasols, and discreet services. Everything you could want from a beach.

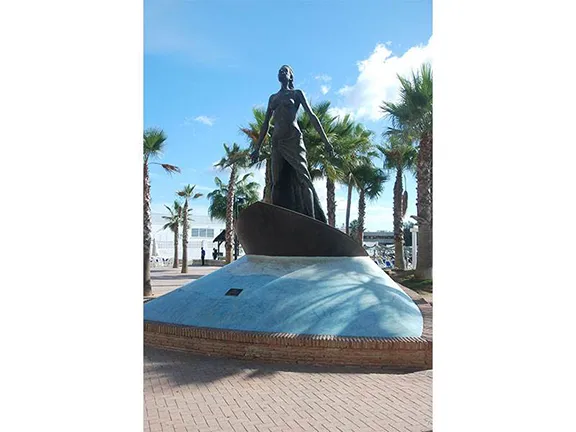

Mermaid on the paseo at Fuengirola

Behind the beach is the paseo. Although broad and a favourite route for joggers and all those, oh so determined pre-breakfast walkers, ploughing on with walking pole in each hand, carving through the unwary family group like battleships parting the waves, it does lack any decorative features.

Overlooking the paseo and beach are row after row of bars, cafes, and restaurants. The competition is tough. Who has the best-priced drinks, breakfast, menu del dia, the largest TV screen for the football? It is difficult to judge but it seems as though English is the first language on this strip. English is certainly the favourite taste on the menus. Do not worry if you do not speak English, most of the menus have pretty pictures so you can just point at what you want. Although it appears like Blackpool promenade in the sun, look a little harder. There are some little gems. The occasional fish restaurant setting up for lunch with, gasp, linen table cloths and napkins and polished glasses. Here and there somebody’s idea of designer catering. You can usually tell by the uncomfortable chairs and hand-painted pastel tones, but do not be too quick to scorn. Some do a proper breakfast with Lincoln sausages and have imaginative lunch and dinner menus and very good coffee. The message here is as elsewhere, you get what you pay for and in Fuengirola, the range between worst and best, cheapest and most expensive, is huge.

Paseo Jesús Santos Rein

It is behind the paseo that Fuengirola starts to surprise. There are a few narrow streets in more or less a grid pattern, the ones south of the marina having the appearance of age, and this is the area in which the fishing families lived before the tourists discovered Fuengirola. 200 metres behind the paseo, and parallel to it, is Paseo Jesús Santos Rein. Two kilometres of shops. Some modern and classy, interspersed with a family greengrocer, Versace alongside Veg, a small Panaderia next to Prada and of course some traditional type souvenir emporiums. A stewpot mix that reflects Fuengirola’s atypical, chequered history.

Fuengirola started off life back in Phoenician times; a small settlement on the 40-metre-high mound now topped by Suhail castle. The Romans recorded the settlement name as Suel. Pliny the Elder tells us that, by the 1st century AD, it was an oppidum, or fortified town.

Finca del Secretario

Outside the town walls, to the north, was a villa and fish salting plant, together with the ovens required to manufacture the amphorae that were used to transport the products of this small industrial unit. These types of villa, both home to a well to do family, and centre of commercial activity, were scattered about Andalucia. At the north end of Paseo Jesús Santos Rein, is the archaeological site of Finca del Secretario. Discovered during the construction of the bypass and railway line in the 1980s, excavations were carried out spasmodically over a period of 20 years to gradually reveal a fish salting plant, amphorae manufacturing factory and a public baths area. The villa, Finca del Secretario, is outside the archaeological area and still awaiting excavation. Even so, the site is one of the better examples of a Roman industrial unit in Andalucia. Completely free to enter, with an Interpretation Centre and a café and disabled-friendly paths, it deserves more publicity than it receives.

Suhail Castle

In November 2022, archaeological works next to Sohail Castle, site of the Roman port of Suel, revealed the 700 square metre remains of a public building with marble floors, walls and pedestals that could have supported statues. The quality of the construction reinforces the view that Suel was a major part of the Roman commercial trading network on the Mediterranean coast. Indications are that Finca del Secretario was an important part of the industrial and agricultural industry in the area, importing and exporting products to all parts of the Roman Empire.

The Romans departed and the Moors moved in. They changed the name of the town to Suhayl and in the 10th century built the castle of the same name, on top of the Roman foundations. A settlement grew up around the castle and the surrounding area was given over to agriculture with hamlets dotting the landscape. Records show that a succession of Moorish rulers used the land as pasture for their camels. Sometime during the 14th century, a fire devastated the settlement around the castle and the population moved to the neighbouring settlement of Mijas. The castle and settlement became ruins.

In 1485, the area was reconquered by the Christian forces of Ferdinand and Isabella. The Spanish historian, Alonso de Palencia, tells us that the remains of the fortress and ruined settlement were then known as Font Jirola after a spring that rose at the foot of the castle. It is from this name that the current name of Fuengirola derives.

Following the reconquest, the coast was plagued by raids from Barbary pirates. People were reluctant to live on the coast. An attempt was made to repopulate Font Jirola with 30 people but, despite being promised free land and what would today be called a municipality, nobody took up the offer. In 1511 the area was recorded as uninhabited apart from a mention of a watchtower, and the land became part of Mijas.

Gradually the threat from pirates diminished and by the late 17th century, people had started to move back into the area. In the early 18th century an inn appeared near the beach establishing the raison d’être for Fuengirola as we know it today. A small village grew that survived by trading the agricultural produce of the hinterland with ships that anchored in the bay and by fishing.

Artillery at Suhail Castle

In 1810, during the Peninsular War, Sohail castle at Fuengirola was garrisoned by a detachment of the Polish Army of Warsaw, allies of Napolean Bonaparte. The garrison comprised 150 Polish soldiers and 11 French dragoons with two light cannons mounted on the castle walls. Their task was to prevent arms from Gibraltar being supplied to Spanish partisans. In October 1810, the British Major General Lord Blayney decided to capture the castle at Fuengirola with 3,500 British troops augmented by 1,000 Spanish partisans. In an epic battle, now legendary in Polish and French military history, Blayney was defeated and captured. His surrendered sabre is on display at the Czartoryski Museum in Cracow.

By the 20th century, Suhail castle was again showing its age. Renovations began in 1995. By the year 2000, the interior of the castle had been cleared to allow the space to host concerts and festivals. The mound was landscaped and the site is now a popular place to stroll and relax. Entry to the castle is free.

At the southern end of Paseo Jesús Santos Rein is a destination that Fuengirola can be proud of, Bioparc Fuengirola. Once a conventional zoo, Bioparc Fuengirola championed an animal park model based on a respect for nature and the preservation of animal species. At Bioparc, realistic habitats have been created, Madagascar, Equatorial Africa, Southeast Asia and the islands of the Indo-Pacific. Within those habitats, a number of animals live together, not in separate cages, just as they would in the wild. The result is a natural habitat for those animals. Part of the design involves visitor immersion, the visitor becomes immersed in the habitat, with the animals. The Fuengirola Bioparc has created a benchmark for other Bioparks in Europe. Well worth a visit for adults and children.

Meanwhile, Fuengirola had grown from a population of less than 3,000 in 1960 to well over 70,000 at the turn of the century; fueled by the increasing numbers of northern Europeans wanting a week in the sun.