The Rio Guadalquivir is 657 kilometres long and is the only major navigable river in Spain. Its source is in the Sierra de Cazorla and its estuary is on the Atlantic coast in Cadiz province. It flows through four of Andalucia's eight provinces.

By Nick Nutter | Updated 25 Apr 2023 | Andalucia | History |

Login to add to YOUR Favourites or Read Later

Rio Guadalquivir at Córdoba in March 2023

The Rio Guadalquivir has been home to humans since the first hunter gathers appeared in the area over 500,000 years ago. Its fertile soils were discovered by Neolithic people over 6500 years ago and the Guadalquivir valley has been continuously occupied ever since. The waters of the Guadalquivir have sustained people since the dawn of history and two of Andalucia’s greatest cities, Seville and Córdoba would not exist without the river that flows through them. Since its birth, about 10 million years ago, the Guadalquivir has been instrumental in forming the landscapes we see today. It is even responsible for the creation of the Mediterranean Sea. The Guadalquivir is not a river to be taken lightly.

In March 2023, I was in Córdoba and saw the Guadalquivir at the lowest levels that I can remember in over 20 years. The river that powered water wheels for flour mills during the Roman and Muslim period and that allowed river craft to navigate upriver as far as the Roman bridge was still, almost stagnant, dying. 657 kilometres downriver, in the Doñana National Park where the Guadalquivir empties itself into the Atlantic Ocean via a huge salt marsh, the gullies were dry, the waterfowl that lived in the marshes, numbering hundreds of thousands, were abandoning their traditional nesting sites and the migratory birds that swelled the resident population every year were finding new pastures. In September 2022, the Santa Olalla lagoon, the largest of the permanent bodies of water, which quenches the thirst of thousands of migratory birds and mammals, dried up, leaving the rest of the wetlands arid. Admittedly, the situation in the Doñana is exacerbated by the use of wells to irrigate farmer’s fields.It appears that the Rio Guadalquivir is in dire straits.

Waterwheel at Córdoba high and dry

Ancient people believed that rivers and streams had souls, that they were living things with emotions. They knew that the watercourses were vital for their own continued survival and were just as much a part of the landscape as they were. In fact they probably considered the river more significant than themselves. If a river or stream dried up then that was a calamitous event that required the intervention of powerful gods and the sacrifice of the shamans that had allowed this to happen. For without the water, they would either perish or be forced to move their homes. Now, I am not suggesting that we slaughter any shamans, first find your shaman, but the apparent sadness of this once impressive waterway, now reduced to a trickle, has prompted me to record the history of this once proud river before it disappears entirely.

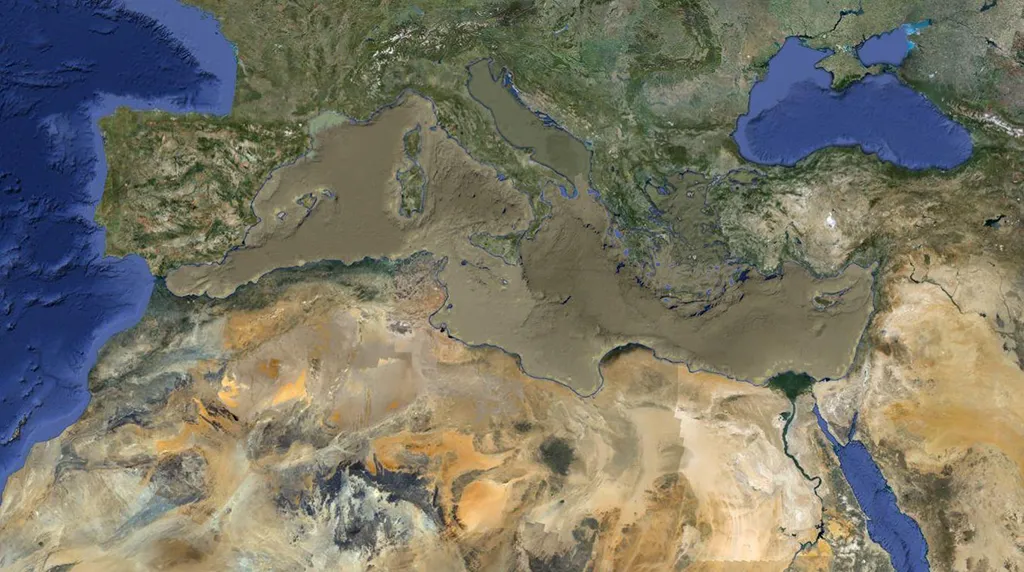

Europe during the Miocene

The Rio Guadalquivir has been around for far longer than any humans. It’s origins lie way back in the Miocene epoch that lasted from 23 to 5.33 million years ago. In those days, the map of Europe was very different to that of today. Spain was divided north and south by a seawater channel that connected the Atlantic Ocean with the Mediterranean basin. To the north of the channel was the proto Sierra Morena, whilst to the south were the infant Cordillera Subbetica mountains. Both mountain systems were gradually rising, being pushed upwards by the forces acting on the tectonic plates beneath.

About 5.96 million years ago, the rising land and moving tectonic plates sealed off the eastern end of the Guadalquivir depression as the Sierra de Penibética mountains to the south and east joined with the Sierra Morena mountains to the north. The seawater drained from the depression creating a triangular valley that was 30 kilometres wide at its western end and narrowing to a point some 200 kilometres to the east. This became the watershed and catchment area of the Rio Guadalquivir. The valley bottom was composed of deposits laid down when the depression was beneath the waves. Over millennia, these were eroded out by the Guadalquivir and its many freshwater tributaries and replaced by fertile soils washed down from the mountain slopes to the north, east and south.

Nacamiento - birth place - of Rio Guadalquivir

The Rio Guadalquivir emerges from beneath the limestone rocks high in the Sierra Cazorla. It flows north and then west to Garganta and then south west to Ubeda. In the upper reaches, the river occupies a narrow gully, gradually becoming wider as the steep slopes of the sierra give way to the lesser slopes towards Garganta. There it turns west again as far as Andujar where it again turns to the southwest to Córdoba, the valley becoming wider. From Córdoba it continues southwest, meandering all the way to Seville from which city it heads due south through the low lying salt marshes of the Doñana Parque Nacional until it flows into the Atlantic Ocean at Sanlucar de Barrameda. In its lower reaches, the Guadalquivir valley is a wide, low lying valley with gently rolling hills, never more than 150 metres high.

Guadalquivir in its middle course

At the same time, the African tectonic plate pushed into the European plate, closing the channel between the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Basin. Over the next few thousand years, the sea in the now land locked basin evaporated, an event known as the Mediterranean salinity crisis.

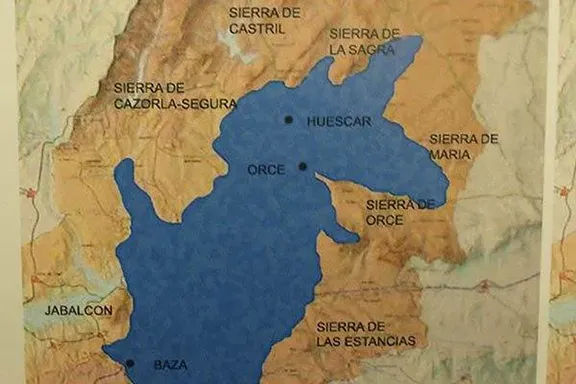

Lake Baza

One further result of the uplifting that was to influence the life of the Rio Guadalquivir many thousands of years later, was the creation of a large landlocked lake, now known as Laze Baza. Lake Baza was separated from the Gualquivir valley by the Sierra Cazorla.

Just before the Zanclean Deluge

For thousands of years, the Rio Guadalquivir flowed through its valley, emptying into the Atlantic Ocean somewhat south of its current estuary, close to where the Gibraltar Strait is today. Dozens of tributaries flowed down the northern slopes of the ridge that had been uplifted when the Mediterranean Basin was cut off from the Atlantic Ocean. 5.33 million years ago, some of those tributaries cut back through the ridge and the Atlantic poured into the basin creating the world’s largest ever waterfall. Within 37 years the Atlantic had filled the Mediterranean basin. This event is known as the Zanclean Deluge. Meanwhile, the estuary of the Guadalquivir migrated west and north to its present position.

Rolling plains of lower Guadalquivir

For the next 5 million years, the Rio Guadalquivir continued forming the landscape we see today. The lower parts became mature and meanders formed in the river, west of Córdoba city. Between 500,000 and 240,000 years ago, the Rio Fardes eroded a gap at the southwestern end of the Sierra Cazorla and joined up with the Guadiana Menor, a tributary of the Rio Guadalquivir. Lake Baza drained into the Guadalquivir over a fairly short period of time, measured in hundreds rather than thousands of years. The increased flow helping to cut the river terraces noticeable between Córdoba and Seville. This was at a time when the first human hunter gatherers, Homo heidelbergensis, were starting to move across the landscape in Andalucia.

Doñana in 2015 - very wet

Until the Neolithic period, starting about 6,500 years ago, humans had little impact on the landscape. Agriculturists however had to deforest vast areas of land to create arable land for growing crops and pasturing livestock. Throughout the Guadalquivir valley, the dehesa began to be created. An unfortunate consequence of the land clearance was an increase in the erosion of the topsoil. The sediments were taken by the Rio Guadalquivir and emptied out into a bay of the Atlantic Ocean in the vicinity of Seville city. An estuary began to form as the sediment settled on the seabed. Until this period, the flow of water down the river had been powerful enough to take the sediment into the deeper waters of the Atlantic Ocean.

It was not until the Roman period, just into historical times, that the bay became marismas and the Doñana began to form. Today the Doñana covers about 2,000 square kilometres.

Rio Guadalquivir at Seville

Rivers have always been used as arteries, easy routes between places and the Rio Guadalquivir is no exception. During the hunter gatherer period the banks of the river were used as tracks. Later, after the invention of hollowed out tree trunk canoes, the river itself became the route. Neolithic people used the river as a means of communicating between their settlements along the valley.

The Guadalquivir was the main route between those settlements, an artery for communication and produce. Over time the major settlements became market towns, the hubs for outlying, smaller settlements and homesteads. The produce carried on the river would have been livestock, vegetables and grain, and trade goods such as pottery, woven materials and leather.

When metallic ores began to be exploited after about 2500 BC, the settlements close to the mines, particularly in the upper reaches of the river in the foothills of the Sierra Morena and centres of metal working such as at Valencina de la Concepcion just west of Seville, became ever more important, especially so when the Greek and Phoenician traders arrived off the Atlantic coast after 1000 BC. Grapes, olives, wine and oil, metallic ores and finished copper and bronze artefacts travelled downriver and exotic goods from the eastern Mediterranean and as far away as Portugal, northwest France and Britain were transported upriver. By the time the Romans arrived there was a well-established trading network up and down the Guadalquivir.

The Romans of course liked to make things better and more efficient. One of their initiatives was the building of permanent, stone piers and jetties at strategic places along the river to facilitate the storing and movement of produce.

The Muslims continued and increased the trade running up and down the Guadalquivir with much of the produce being transported to the eastern Mediterranean.

Following the reconquest and the discovery of the Americas, trade along the river again saw an upsurge. Seville became known as the ‘Gateway to the Indies’.

Industrial exploitation of minerals during the 19th and early 20th centuries saw the introduction of the railway lines along the Guadalquivir valley connecting Seville with Córdoba and the main mining centres in the surrounding sierras. Meanwhile, the road along the valley, paved by the Romans, was improved towards the middle of the 20th century.

Today, although now over 100 kilometres from the sea, Seville is still a major port with cargo ships able to navigate the tidal waters. It is the only inland port in Spain and has recently started to attract cruise ships.

The Rio Guadalquivir is tidal as far as Alcalá del Río, 117 kilometres from the estuary. In 1930, the Alcalá del Río dam and reservoir was built to provide a source of hydroelectricity and allow irrigation of agricultural land. Downriver of the dam, the tidal range is 3.5 metres.

Hunter gatherers found the fish in the Rio Guadalquivir an invaluable resource. They would have visited the banks of the river on an annual basis, it would have been part of their perennial movement between lowlands and uplands.

Later, Neolithic people would start to use the waters of the river to irrigate their crops and this practice has continued to this day. The Rio Guadalquivir provides the waters in Jaén province to irrigate the vast olive groves that cover 90% of the cultivated land, the soy beans, peanuts, sunflowers, olive groves corn and wheat in Córdoba province. In Seville province it nurtures cereals, rice, legumes, cotton, vineyards, citrus fruits, non-citrus fruits such as peaches and in Cádiz province the famous strawberry fields of Jerez would not exist without the Rio Guadalquivir.

Guadalquivir Estuary at Sanlucar de Barrameda

The river has also been a source of inspiration for many artists and writers throughout history. The famous Spanish poet Antonio Machado wrote several poems about the Rio Guadalquivir, praising its beauty and its importance to the region. The river has also been featured in many paintings and photographs, capturing its unique charm and character.

The Rio Guadalquivir is a grand old lady. She is over 10 million years old and has seen mountains rising around her. She witnessed the arrival of humans and watched them develop agriculture and build cities. She has seen and withstood climate change and tolerated human intervention. Until today. What will happen in the future is not known. I rather suspect that the grand old lady will outlast humans and see yet another episode of geological and climate change unperturbed by those strange two legged creatures that insist on floating along with her.

Écija, in the Guadalquivir valley in Seville province, has, for years, been known as ‘La sartén de Andalucía’ (the Frying Pan of Andalucia), and not without justification.

Spain's meteorological agency Aemet has predicted temperatures in the Guadalquivir valley, Andalucia in southern Spain, 'could reach 40C' during the last week in April 2023. The heatwave is being caused by hot air from the African continent being drawn over the Iberian peninsula.

Whilst these sorts of temperatures are normal in the Guadalquivir valley during late June, July and early August they are certainly abnormal during April. Abnormal enough to make the headlines on the BBC News site, the Daily Mail website, and in more local papers such as SUR in English and the Olive Press. If it happens, then 2023 will break previous records reached in 2022. Average summer temperatures have been increasing in the Guadalquivir valley for over 20 years. 2017 was the first occasion when a summer in Córdoba exceeded the barrier of 38°C on average, and the first time that all three months registered maximums of 44°C or more in the same year. Temperatures over the last few years have maxed out at over 40C on 25 days or more during the three summer months.