The Megalithic dolmens alongside the river Gor is the greatest concentration of dolmens in Europe and part of the Geoparque Granada project

By Nick Nutter | Updated 4 Jun 2023 | Granada | Places To Go |

Login to add to YOUR Favourites or Read Later

La Colorado Gorafe

Standing on the edge of a broad plateau, at a height of over 900 metres above sea level, overlooking the arid Badlands that surround the village of Gorafe, it is difficult to imagine why it was such a popular spot for our ancestors 6,000 years ago. Even more difficult to imagine why those ancestors, for 2,500 years, had the inclination to build over 240 megalithic burial chambers.

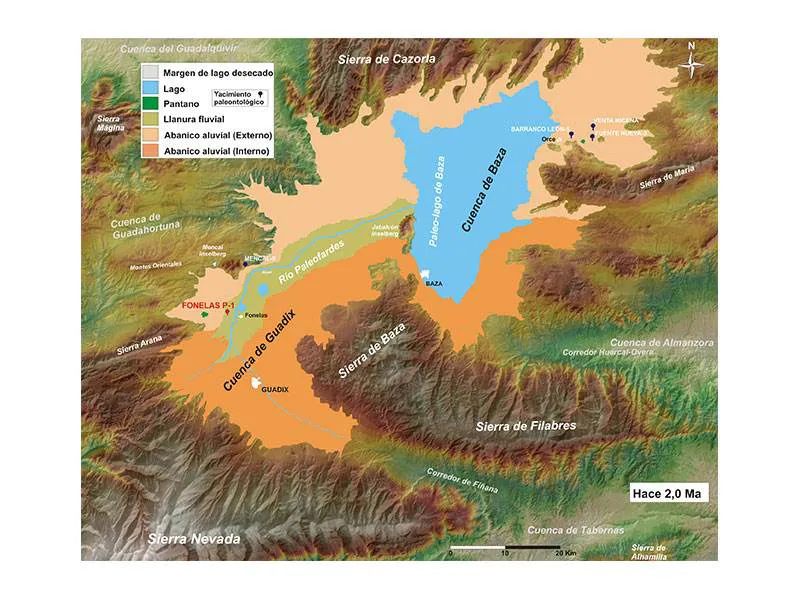

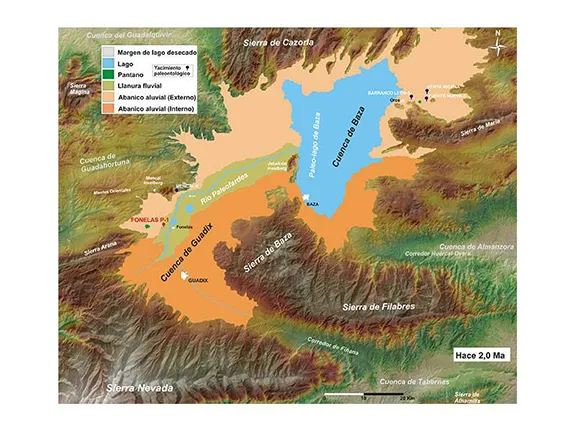

Hoya Guadix Baza Depression and Lake Baza

The story starts some 2 million years ago when the climate was much wetter than it is today. A lake existed in the Hoya Guadix - Baza depression that stretched from north of Huescar to Baza in the south.

Over the following millennia, the climate changed, and the lake dried out. Meanwhile, the River Gor with its headwaters in the Sierra de Baza, flowed north across the plateau on which we are stood, picking up tributaries from the Sierra as it went. At the same time as Lake Baza was retreating, the river was carving out a deep canyon through the soft sandstone, now known as Los Colorados due to its similarity, albeit on a smaller scale, with the Grand Canyon in America. As the climate became drier, the sides of the canyon collapsed into the valley floor. The Gor continued flowing and another, smaller ravine, developed at the bottom of the canyon.

Meanwhile, tributaries carved out their channels from the top of the plateaux. The result can be seen today. It is known as Badlands; deep gullies with arid sandstone buttes and bluffs between the flat plains of the remaining plateaux. The rock is horizontally banded with red, yellow and white strata. It is a stunning, beautiful and cruel landscape.

.webp)

-sm.webp)

Dolmen 65

Six thousand years ago, the dry episode had not quite reached the aridity of today. The climate was wetter and probably a little cooler than at present — ideal conditions for cultivation in the fertile ground in the valley of the River Gor. The primary vegetation, shrubs, herbs and trees, was not much different to that of today in the wetter parts of Andalucia, olive and oak, plantain, thistles, gorse, grasses, broad-leafed herbs and so on, ideal for a wide variety of species of herbivores including wild horses, mountain goats, boar, roe deer and deer. Conditions were so good for the Neolithic families that about eleven separate settlements established themselves in the River Gor valley over a distance of about 10 kilometres. All the sites have been identified, and one has been studied in some depth.

Hoyas de Coquin in the centre of the picture

As the population of the settlements increased, it became ever more critical that each settlement could lay claim, and defend, their stretch of the valley. The defence was relatively easy. Each settlement was on a mound within the canyon. A wall surrounded the round huts within and a gate, presumably closed each night, allowed access. The site of one such settlement, Hoyas de Coquin, has been examined and can be considered typical. Travel north towards Gorafe on the GR 6100. The road descends in a series of hairpins from the top of the plateau to about halfway down the cliff where the collapsed sides of the canyon form a series of ridges with relatively flat surfaces before falling off again towards the River Gor. The settlement is situated on a mound about 100 metres west of the GR 6100 road, immediately after the last hairpin, between the road and the ravine containing the River Gor. A depression on the facing side (east) of the mound is man-made. The Neolithic people excavated a channel to take the runoff from any rain to prevent erosion of their mound. The enclosure protected approximately 20 circular huts.

Identifying and laying claim to their land was somewhat more problematic for the Neolithic people, and this is where the dolmens came in. The dolmens are grouped according to the settlement that owned them. They are built either on the rim of the plateau or on the top of mounds on the collapsed sides of the canyon. There are basically two sizes, large dolmens that, due to the size and weight of the stones used in their construction, would have required the cooperation of the entire settlement to build and smaller dolmens that could, conceivably, have been built by one family. The larger dolmen was the burial chamber for the head of the settlement whilst the smaller would have been for the individual families that made up the tribe. Some of the dolmens had been used for multiple burials over a long period. One had bones from over 20 individuals within it. The larger dolmen was placed overlooking the settlement and the land surrounding it. Although eleven groups of dolmens have been identified, each associated with a known settlement, it is not yet known how, exactly, the Neolithic people then determined how much or which, land belonged to each settlement.

Although all the megalithic funerary structures at Gorafe have been labelled dolmens, this is not quite accurate. Passage graves and corridor tombs are more numerous than the simple dolmen.

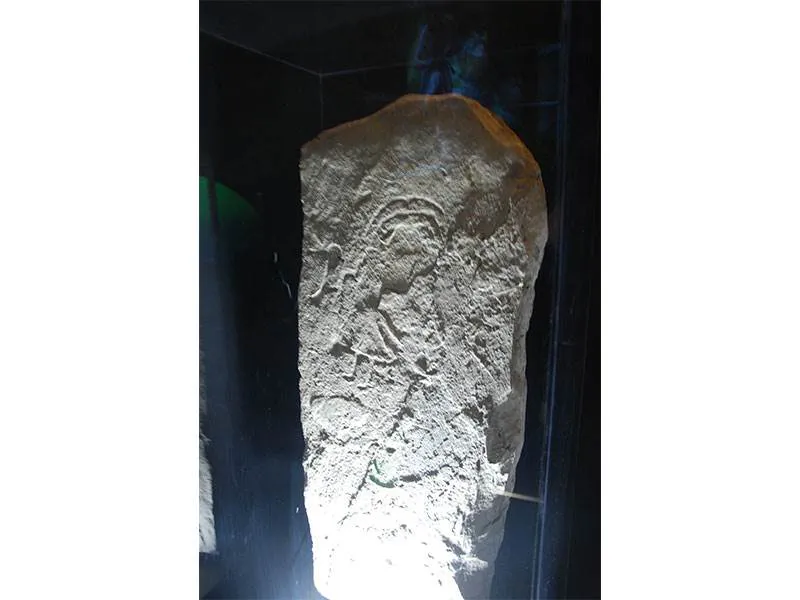

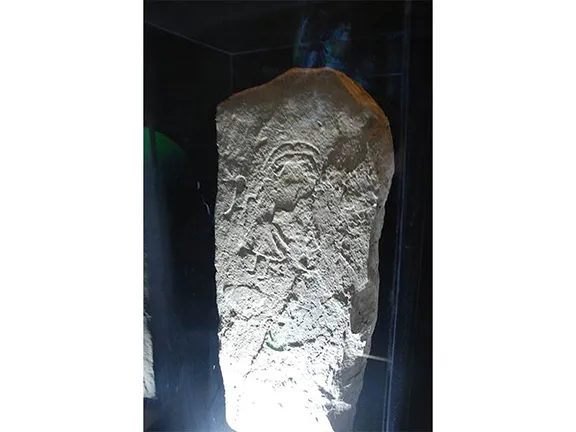

Orthostat with engraving

Only one stone carrying any inscription has been found in any of the Gorafe dolmens so far. The stone, 97 cms high, is an orthostat (a vertical stone defining the sides of the chamber or passage, used as support for the capstones). It was found in Dolmen 77. The engraving is on the reverse face, that is the face of the stone against the soil, so ordinarily invisible. It depicts an anthropomorphic figure, clothed in a gown or cape, with a feathered headdress, holding a cane or tool of some sort in his right hand. The stone is doubly important since it is only the second of its kind in Andalucia.

The concept of building megalithic monuments originated in northwestern Europe, around the area now known as Armorica, Gaul and Brittany. The idea probably started as a need to monitor the seasons by erecting vertical stones and then stone circles. Individual upright stones are called menhirs and stone circles are called cromlechs. Menhirs may have served two functions, as boundary markers or as rallying points, known locations for meetings at important times of the year. Each tribe had communication with those around it, and it is through this communication that individual objects, such as polished stone axes, travelled across the landscape, hand to hand. It is also the mechanism by which ideas, such as styles of pottery, spread. In this case it was a concept, that of megalithism, that spread outwards from Armorica. The concept had to include the reasons why it was a good idea to raise these stones, plus, in the case of stone circles, how they should be laid out to give the desired result and how the stones could be moved and erected. It must have taken quite a few nights around the campfire to go through it all.

The megalithic concept reached Portugal, specifically the area around the Tagus estuary. In this region, the population were still, predominantly, Mesolithic. In other words, hunter-gatherers. They lived in a privileged area in that everything they needed to survive and prosper lay within a small radius. In other regions, hunter-gatherer may have had an area of a few hundred square kilometres to cover every year to find the resources to keep a small family alive. The Mesolithic people around the Tagus had started to form permanent settlements, a very unusual practice for hunter-gatherers. They had also begun to bury their dead within shell middens, huge mounds of seashells discarded over the ages after the population had consumed the contents. The burial chamber was often at the end of a short passage, and one shell midden could contain many chambers.

The Neolithic people expanded their territory from the east and eventually met the Mesolithic people on the Atlantic seaboard of the Iberian peninsula. The Mesolithic people resisted the Neolithic practices for hundreds of years, yet, according to DNA research, there seems to have been communication between the two groups. They also had one thing in common, a desire to revere their ancestors.

Meanwhile, the megalithic concepts were spreading from the north and eventually reached the Mesolithic tribes and the Neolithic people over in the western part of the Iberian peninsula. Portugal has hundreds of menhirs and dozens of cromlechs.

A melting pot of concepts and ideas met and fused. Shell midden mounds used as burial chambers and as designators of territory. Methods of carving large slabs of stone out of living rock and then moving those slabs across the landscape. How to raise the stones to fix them in position. The idea of those standing stones being marker posts and meeting points. Growing awareness of self and family and tribal unity probably exemplified by the use of idolic plaques. A whole raft of ideas and techniques that offered a solution to a problem that was increasing. Lack of land. As the Neolithic numbers increased, available land for agriculture and stock raising was at a premium. It became necessary for individual families and tribes to mark off and defend their rights to land.

However, and for whatever reason, it happened, the megalithic dolman was born and the practice of building them spread from Portugal, back through the Neolithic territories, east through southern Spain and back north to Brittany and beyond. The cromlech and menhir ideas seem to have been discarded along the way. In the Iberian peninsula, outside of Portugal, there are very few menhirs and even fewer cromlechs, and to the north, through to Brittany, where menhirs were abundant, many were re-used in dolmens. Fortified settlements started to appear at about the same time.

Dolmen 71

Eventually, about 3000 BC, megalithism arrived at Gorafe. Within the valley of the River Gor, the Neolithic people were increasing in number due to the ambient conditions and increasingly needed to demarcate their land. Megalithism was an idea that arrived at the right place at the right time, hence the concentration of dolmens not seen elsewhere in Europe. The practice of using dolmens as burial chambers in the Gorafe area continued through the remainder of the Neolithic, through the Copper and into the Bronze Age, that is until about 1500 BC.

The dolmens were first examined in a systematic way in 1868 by Manuel de Gongora. He was followed by Luis Siret, a Belgian mining engineer, who excavated many sites including the copper age site of Los Millares in Almeria. In the early 20th century the German archaeologist team of, Georg and Vera Leisner looked at the construction techniques and distribution of the dolmens, but it was not until 1959 that they were properly numbered and catalogued. Manuel Garcia Sanchez and J.C. Spahni conducted this work between 1955 and 1959.

It is only recently that there has been a surge of interest by Spanish academics in the prehistory of Spain. Part of the reason is economical, Spain could not afford to fund the research, and part is an unawareness of the richness of Spanish history in general and prehistory in particular. Today an increasing number of academics are producing papers and, most importantly, having them translated into other languages. When sites of particular importance are found then money, often helped by the EU, is made available to disseminate the information gleaned to a broader audience.

In 2011 a Centro de Interpretación del Megalitismo, a Megalithic Interpretation Centre, was opened in the small village of Gorafe. It is built underground, beneath a mound, to emulate a dolmen and is being visited by an increasing number of people interested in the megalithic phenomenon.

The Altiplano of Granada also makes its mark in geology. The Granada Altiplano provides geologists with a complete continental sedimentary record of the Quaternary period on the planet. Forty-seven municipalities in the Hoya de Guadix-Baza depression, that started to form 65 million years ago, have been included in a project to promote the landscape, the cultural and the geological value of the area. It is hoped that the project will encourage people to observe, appreciate and understand the fossils, minerals, deserts, ancient burial sites and the archaeological and paleontological sites within this unique area. The project is called Geoparque Granada.

A geoparque (geopark or geoparc) is a well-defined territory, home to a valuable natural geological heritage. The most important parts of a geoparque, due to their scientific, aesthetic, or educational value, are called geosites.

In the north of Granada, surrounded by some of the tallest mountains of the Iberian peninsula, what we know today as the Basin of Guadix or the Guadix - Baza depression or basin was, for 5 million years, a lake with no outlet to the sea. Sediments, brought down by the mountain streams, were deposited in the basin in horizontal sheets. 500,000 years ago the basin drained to the west and new streams carved out the canyons, ravines and badlands that characterise the area, the most southerly desert in Europe, today.

The valley of the River Gor is a geosite by virtue of its concentration of megalithic dolmens.