The Emirate of Granada, founded by Muhammad ibn al-Ahmar, took 24 years to stabilise and endured for two and a half centuries

By Nick Nutter | Updated 11 Apr 2023 | Andalucia | History |

Login to add to YOUR Favourites or Read Later

Castle at Jerez de la Frontera 11th - 13th century

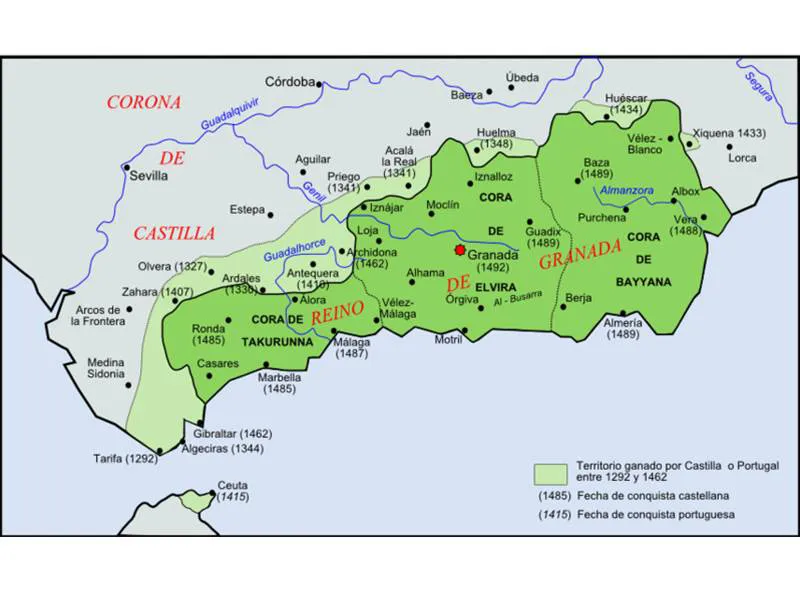

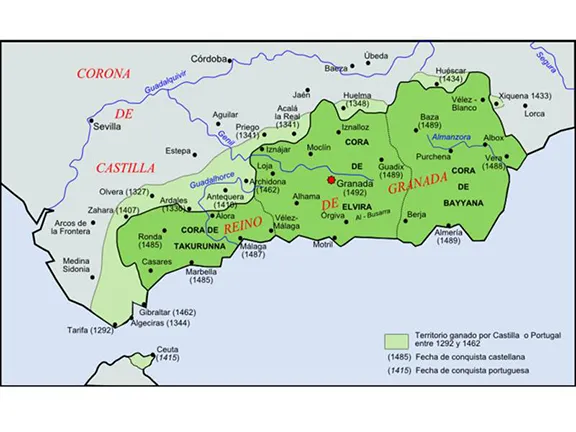

The Nasrid dynasty, founded by Abu Abdullah Muhammad ibn Yusuf ibn Nasr in Granada, endured for two and a half centuries. After the defeat of the Almohads at the battle of Las Navas de Tolosa (1212) and the subsequent rapid fall of major cities in al-Andalus (Badajoz 1230, Córdoba 1236, Valencia 1238, Murcia 1243, Seville 1248, and Cádiz in 1265 all to Castile and León, and the Balearic Islands –Mallorca, Menorca and Ibiza– between 1230-35, to Aragón), the survival of the kingdom of Granada comes as something of a surprise. The total demise of al-Andalus, that now consisted of only Granada, and parts of the provinces of Jaén, Almería, Málaga and Cádiz, collectively known as the Emirate of Granada, and a few Muslim enclaves such as Niebla and Jerez on the borders of the Emirate, seemed imminent.

Alhambra started 13th century

So why did Ferdinand III of Castile-León and his ally, James I of Aragón not continue to roll up the Muslim territories?

Geography

The first factor was the geography of the Emirate. The Emirate of Granada consisted of huge tracts of inhospitable mountains, including the highest in the Iberian Peninsula, with dangerous passes and steep valleys, not an ideal terrain for Mediaeval – Christian style warfare. The Emirate was eventually protected by no less than 14,000 watchtowers placed in strategic positions, such as the one shown above, Aljambra Torre near Albox, overlooking the Almanzora valley, and numerous fortified towns built on impregnable buttresses and crags in the mountains, such as the ones shown above at La Iruela and Zuheros, all with light cavalry that were suited to the rough terrain. The ruins of these towers can still be seen and are most prolific in Jaén, Granada and Almeria. The fortified towns, such as Jerez de la Frontera, shown above, are scattered throughout Andalucia, with an emphasis on the frontier areas. Many of the ‘white villages’ also date from this period.

Territorial disputes

Secondly, the Christian allies could not agree amongst themselves at a fair division of the newly gained territory. Competition between Castile and Aragón was fierce until 1244 when a treaty was signed that limited the amount of territory that Aragón could have from al-Andalus. This happened to play into Aragón’s hands. Their real ambition was to establish an overseas trading empire based on Barcelona. That ‘empire’ soon included Sardinia, Corsica, Sicily and even Athens.

Logistics

The third problem was logistical. Between the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa in 1212 and 1248 AD, the kingdom of Castile-Léon almost doubled in size. The loyal Christian population was not sufficient to both populate and defend new territories and assemble an aggressive army. The history of many individual towns, particularly on the north and east frontier, is one of populations being displaced and then repopulated from elsewhere. The loyalty of the population in the conquered territories also played a part. The Christians were predominantly Mozarabs, speaking Arabic and adopting elements of Arabic culture including clothing. The majority of Muslims for their part evacuated to the Emirate of Granada as the Christian forces advanced south. The remainder stayed in place. Muslims that remained in Christian lands were called Mudéjars. Both Mudéjar and Mozarabs were treated as second class citizens under Christian rule. They were often looked upon with suspicion by the incoming Christian forces and the administrative support that followed, suspicions that became reality during the Mudéjar Revolt of 1264 – 1266 AD.

Mozarab numbers in the conquered territories were bolstered after 1248 when Muhammad ibn al-Ahmar, a staunch defender of Islam and Islamic culture, expelled all remaining Christians from the Emirate of Granada. His reasons were simple. He feared an internal revolt by Mozarabs that would help the Christian forces of Castile-Léon and Arágon if they did decide to invade. The only Christians granted access to Granada were now merchants, prisoners, slaves and disaffected nobles seeking support against their rivals. The only non-Muslim communities within the Emirate of Granada were a few Jewish commercial concerns in the coastal towns.

The days of ‘Convivencia’, that had characterised the Muslim occupation were over. It could be argued that those halcyon days ended when the fundamentalist Almoravids took over in 1086 and who were then succeeded by the even more fanatical Almohads in 1145. In any case there had been a steady stream of Christian and Jewish refugees fleeing north for the 160 years prior to the formation of the Emirate of Granada.

As far as Christian opinions went, the solely Muslim population within the Emirate was never considered sufficient to constitute a threat to their kingdoms. There was an uneasy balance of power within the Iberian Peninsula.

Unstable Muslim rule in Morocco

An uneasy balance of power also existed between the Emirate of Granada and the emerging, Marinid dynasty in North Africa and the initially incumbent Almohads. Of concern to both sides, Christian and Muslim, was the threat from North Africa. If all-out war was declared, the Muslims in Granada could ask the Muslims in North Africa for assistance, as had happened in the 11th and 12th centuries. The Muslims in Granada were concerned that the newcomers would establish themselves in al-Andalus, as had the Almoravids and Almohads. The Christian concern was that the newcomers would expand al-Andalus at the expense of Christian holdings.

Castile's agreement with Granada

In addition to the internal Christian politics and logistical problems, there were a series of agreements between Ferdinand III and Muhammad ibn al-Ahmar.

Muhammad ibn al-Ahmar inherited the taifa of Granada in 1238. Over the next few years he formed an alliance with Ferdinand III that had four major conditions that Ahmar had to conform to in order to guarantee the continued existence of the Emirate of Granada. Ahmar agreed to become a vassal of King Ferdinand (hence the Emirate of Granada was a vassal state), he had to forfeit Jaén, pay an annual tribute to Castile-León, a parias, and assist Ferdinand in his war against other Muslims. So it was that Muslim troops under the banner of Muhammad ibn al-Ahmar, fought alongside the Christian troops of Ferdinand III of Castile-León during the battles to take Córdoba in 1236 and Seville in 1248. Mind you, al-Ahmar had an ulterior motive at Córdoba, the emir of Córdoba was challenging al-Ahmar for the throne of Granada. Such was al-Ahmar’s perfidy, in Arab eyes, that there is no mention of his vassalage to Ferdinand in any of their texts.

Financial incentives

Finally, as ever in the dealings between the Christian kingdoms and the Muslims, there was a financial consideration. According to the agreement between Castile and Granada, Granada was paying Castile a parias, an annual tribute. Whilst Granada remained in a strong trading position with Muslim territories through North Africa to the Middle East the money poured in.

These seem to be the initial reasons why the Christian advance halted and why they did not, immediately after 1248, resume the Reconquista. The 250 years of the Emirate of Granada are a complex series of intrigues, conquests, reconquest and alliances made and broken. The easiest way to understand the period is to look at the events in the Emirate, the Christian territories, and North Africa in parallel.

Iruela castle 13th century

Ferdinand III of Castile-León died in 1252 and was succeeded by his son, Alfonso X. Alfonso had ambitions outside of the Iberian Peninsula. One year after inheriting the throne he invaded Portugal, capturing the Algarve (it was returned to Portugal in 1267). In 1254 he signed a treaty with Henry III of England who was at war with France. Alfonso also wanted to be elected Holy Roman Emperor and considered he had a claim through his descent from the Hohenstaufen line in Germany. In 1256 he entered into a complicate series of alliances and spent considerable amounts of money to further his claim that ultimately proved unsuccessful. To obtain money, Alfonso debased the coinage and then introduced tariffs that destroyed an already weak economy.

The fragile peace with Granada was broken by Alfonso when, in the early 1260s he declared a crusade against the Almohads in North Africa and started to build up his forces at Cádiz and Puerto de Santa Maria, very close to the border with the Emirate of Granada. Alfonso overran Jerez in 1261, a Muslim held enclave just outside the Emirate borders, and installed a garrison there. He then went on to take the Muslim enclave of Niebla in 1261. Alfonso met Muhammad at Jaen in 1262. Alfonso asked Muhammad to hand over Tarifa and Algeciras, strategic ports that controlled the Straits of Gibraltar that would help Alfonso in his crusade in North Africa. Muhammad initially agreed to the hand over but then kept delaying the actual transfer. In the same year, Alfonso expelled the Muslim inhabitants from the enclave of Ecija and replaced them with Christians.

After the Christian initiatives of 1261 – 1262, Muhammad was worried that he would become Alfonso's next target. He began talks with Abu Yusuf Yaqub, the Marinid Sultan in Morocco, who sent troops to Granada, numbering between 300 and 3,000 according to different sources. In 1264, Muhammad and 500 knights travelled to the Castilian court at Seville to discuss an extension of the 1246 truce. Alfonso invited them to lodge at the former Abbadid palace next to the city's mosque. During the night, the Castilians locked and barricaded the area. Muhammad ordered his men to break out and returned to Granada and ordered troops in his border towns to prepare for war. He declared himself vassal of Muhammad I al-Mustansir, the Hafsid sultan of Tunis.

Zuheros castle 13th century

Following their defeat at the hands of Ferdinand and James, there had been increasing disaffection amongst the Muslims in the Guadalquivir valley (Seville and Córdoba), Valencia and Murcia. This eventually resulted in the Mudéjar Revolt of 1264 – 1266 AD, that saw several towns return to Muslim control, notably: Murcia, Jerez, Lebrija, Arcos and Medina-Sidonia. The rebellion was sparked by Castile’s policy of relocating Muslim populations from the areas they had conquered. Relatively peaceful relations with Castile and the Banu Ashqilula, a powerful family who were governors of Malaga and Guadix and who also provided the backbone for Muhammad's army, ended in 1264, when Muhammad turned against Castile and assisted the unsuccessful rebellion of Castile's newly conquered Muslim subjects.

In 1266 the Banu Ashqilula, rebelled against the emirate. When these former allies sought assistance from Alfonso X of Castile, Muhammad was able to convince the leader of the Castilian troops, Nuño González de Lara, to turn against Alfonso. By 1272 Nuño González was actively fighting Castile.

The towns were eventually recaptured by the Christian forces but the event served as a reminder to the Christian kings of the dangers of disgruntled Muslims living under different masters. Subsequently Castile expelled any remaining Muslims from the reconquered territories, thousands of whom fled to Granada, effectively bolstering the Muslim forces there, making a potential invasion of the Emirate an increasingly costly and bloody enterprise.

Almijara, Albox 13th century watchtower

In the 1270s, the powerful Marinid dynasty finally deposed of the last of the Almohads in Morocco. They declared a jihad, holy war, in Spain in order to fulfil what they viewed as Muslim sovereignty and to acquire religious prestige, increasing the concerns of both sides on the Iberian Peninsula.

Emirate of Granada

The emirate's conflict with Castile and the Banu Ashqilula and the issues with the Marinids were matters still unresolved in 1273 when Muhammad died after falling off his horse. He was succeeded by his son, Muhammad II.

Muhammad’s rule is best summed up by the Encyclopaedia of Islam that comments that while his rule did not have any "spectacular victories", he did create a stable regime in Granada and start the construction of the Alhambra, a "lasting memorial to the Nasrids". The Alhambra is today a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Further reading and references

Carr, Matthew Blood and Faith: The Purging of Muslim Spain New York, London 2009

Fletcher, Richards Moorish Spain London 1992

Lomax, Derek La Reconquista Barcelona 1984

Lowney, Chris A Vanished World: Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Medieval Spain Oxford 2006

MacKay, Angus Spain in the Middle Ages; From Frontier to Empire, 1000-1500 London 1977

Menocal, Maria Rosa The Ornament of the World Boston, London 2002