By 1492, the Order of Santiago was more powerful even than the unifying monarchs, Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile and was a threat to the Crown.

By Nick Nutter | Updated 16 Sep 2022 | Andalucia | History |

Login to add to YOUR Favourites or Read Later

Knight of the Order of Santiago

The 12th century was a turbulent period on the Iberian peninsula. The country was divided roughly into two halves, the southern half was occupied by the Muslims, the northern by the Christian monarchs of Castile, León, Navarre, Portugal and Aragón. Towns and villages changed hands many times along the ever-changing border between the protagonists as the Christian armies tried to remove the Muslims from Spain and the Muslims tried to regain territory lost to the Christians. One of the most, if not the most, fought over city at the time was Cáceres, now in Extremadura. It was in the bloodbath of Cáceres that a new order, that of Santiago, was born.

Knight with standard

During the 12th century, warfare was seasonal and depended on able bodied men being available to fight in between the sowing and harvesting seasons. The normal Christian recruit returned home at the end of each season, autumn, and only reported for duty again after the spring sowings. That, and the fact that the peasant population was relatively small, meant that there were never enough personnel to maintain control of captured territory.

What was needed was a military organisation that could also act as administrators of occupied territory. The incentive for such an organisation was the riches and power that came with ownership of land. The incentive for individuals to join was the immediate prospect of enrichment through pillage and plunder.

Land held by the Orders in Spain

To make the organisation politically and religiously acceptable they had to have a holy mission signed off by the Pope. Ostensibly the mission was to protect pilgrims on the road to the three main centres of pilgrimage for Christians; Jerusalem, Rome and Santiago de Compostela in Galicia in northwest Spain. During the 12th century, three Orders were created in Spain, the Order of Calatrava in 1164, the Order of Alcántara in 1166 and the Order of Santiago in 1175.

The members of the Order of Santiago (the name of the Order is a coincidence, the Order of Santiago had nothing to do with the identically named centre of pilgrimage) had a more defined mission than simply protecting pilgrims, their banner was inscribed ‘Rubet ensis sanguine Arabum’: “The sword runs red with the blood of the Arab”. Their remit was to facilitate the removal of the Muslims from Spain.

Order of Santiago

Members of the Orders were drawn from the noble families since many of the sons within those families were impoverished, had little to do and often caused unrest among the local populations.

There is some substance to the theory that the crusades were called to give those rebel knights an outlet for their aggressions well away from their homelands and an opportunity to gain in wealth at the expense of any country they passed through on their way to the Holy Land and in the Holy Land itself.

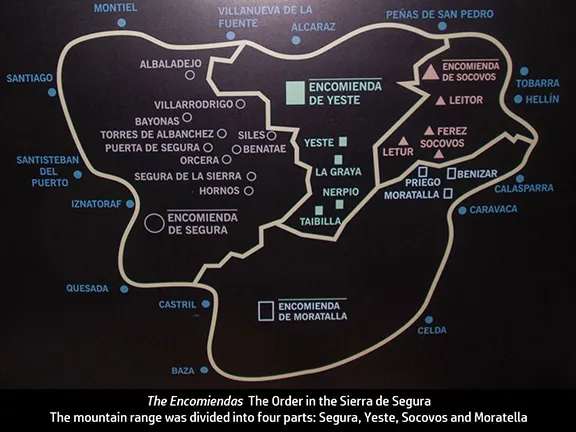

Encomiendas of the Order of Santiago

In 1170, Fernando II de León, together with the Archbishop of Santiago, founded an Order called the Order of the Freiles of Cáceres. The appointed grand master was Pedro Fernández de Castro, an experienced knight. Their task was to defend Cáceres, a town at a strategic position between Christian and Muslim territories. The Order had its headquarters in the city of León. One year later, in 1171, the archbishop was made an honorary member of the Freiles and the Order changed its name to the Order of Santiago.

Castle Segura de Sierra

In 1173, the Almohade army laid siege to Cáceres and eventually captured the town. Forty of the Knights of the Order of Santiago refused to surrender, retreating to the Tower of Bujaco where they fought to the death. The Knights were beheaded and their heads were displayed on pikes. In remembrance of this event, every 10th of March, the Order celebrates the festival of the martyred knights with a mass in their honour.

With no city to defend, the remaining Knights of the Order of Santiago committed to protecting the pilgrims on the road to Santiago de Compostella and aligned themselves with the canons of Saint Augustin. Fernando II de León was not best pleased at losing Cáceres and the wandering knights had to look for another royal patron.

They found one in Castile. In 1174, Alfonso VIII of Castile handed the castle and town of Uclés, now in Cuenca province in Castilla la Mancha, over to Pedro Fernández de Castro on condition that the town be the headquarters of the Order of Santiago. The order now had two headquarters, one in León, the other in Uclés, another bone of contention between the rival monarchs of Castile and León.

Unlike the contemporary orders of Calatrava and Alcántara, which followed the severe rule of the Benedictines of Cîteaux, Santiago adopted the milder rule of the Canons of St. Augustine. At León they offered their services to the Canons Regular of Saint Eligius in that town to protect the pilgrims to the shrine of St. James and the hospices on the roads leading to Compostela. This explains the mixed character of their order, which is hospitaller and military, similar to that of St. John of Jerusalem.

The Order were recognized as a religious organisation by Pope Alexander III, whose Bull of 5 July 1175, was subsequently confirmed by more than twenty of his successors. These pontifical acts, collected in the Bullarium of the Order, secured them all the privileges and exemptions of other monastic orders. The order comprised several affiliated classes: canons, charged with the administration of the sacraments; canonesses, occupied with the service of pilgrims; religious knights living in community, and married knights. The right to marry, which other military orders only obtained at the end of the Middle Ages, was accorded them under certain conditions, such as the authorization of the monarch, the obligation to observe continence during Advent, Lent, and on certain festivals of the year. To prevent temptation, the Knights spent those periods at their monasteries in retreat.

Knights of the Order of Santiago helped Fernando II of León to recapture Cáceres in 1184 in return for ownership of the town. Ferdinand II de León died in 1188 leaving the throne to his son, Alfonso IX de León under whose reign Cáceres was again lost to the Almohads in 1196.

The Knights of Santiago unsuccessfully attacked Cáceres again in 1222 and 1223. The city was finally taken on the eve of April 23rd (St. George’s Day), 1229. Saint George is now the patron saint of Cáceres, and since then, there have always been a fiesta on St. George’s Day celebrating the re-taking of the city.

Following the successful attack in 1229, Alfonso IX disputed the ownership of Cáceres and the lawsuits between the Crown and the Order of Santiago were settled in the Concordia de Galisteo, named for the castle located in Cacereña where the accord was signed. This gave the king the city, but he gave the knights power over the localities of Castrotorafe and Villafáfila and 2,000 maravedíes.

Meanwhile, between 1174 and 1229, the dispute between the monarchs of León and Castile over where the headquarters for the Order of Santiago was situated, León or Uclés, rumbled on. It was finally decided in 1230 when Ferdinand III (Saint Ferdinand), united the crowns of León and Castile.

Ferdinand was the son of Alfonso IX of León and Berenguela, daughter of Alfonso VIII of Castile. At birth, he was the heir to León, but his uncle, Henry I of Castile, died young, and his mother inherited the crown of Castile, which she conferred upon him. His father, like many Leonese, opposed the union, and Ferdinand found himself at war with his own father. In his will Alfonso IX tried to disinherit his son, but the will was set aside, and Castile and Leon were permanently united in 1230. Uclés in Castile became the headquarters for the Order of Santiago.

The Order of Santiago grew rapidly, helped enormously by the mildness of its rules.

Following the Battle of Tolosa in 1212, they rapidly gained territories and possessions in Andalucia, particularly in what is now Jaén province.

Rodrigo Iñiguez, then grand master of the Order of Santiago, conquered Hornos del Segura in 1239.

Siles fell to the Order between 1239 and 1242 and the Knights refurbished the old Arab castle.

In 1242, Sagura de la Sierra was reconquered by the grand master of the Order, Don Pelayo Gomez Correa and King Alfonso VIII of Castile gave the village to the Order of Santiago. The castle at Segura de la Sierra was renovated to house the grand master and the Order built a convent.

In 1247, Santiago de la Espada was taken by Knights of the Order of Santiago who, after 1266, were responsible for repopulating the area.

At its height, at the end of the 15th century, the Order of Santiago had more possessions than the two older orders of Calatrava and Alcántara combined. In Spain these possessions included 83 commanderies, of which 3 were reserved to the grand commanders, 2 cities, 178 boroughs and villages, 200 parishes, 5 hospitals, 5 convents, and 1 college at Salamanca. The number of knights was then 400 and they could muster more than 1000 lances. They had possessions in Spain, Portugal, France, Italy, Hungary and Palestine.

The Order was divided into provinces at the head of which there was a commander with a headquarters, normally a castle such as that at Segura de la Sierra. Within the provinces there were ‘encomiendas’, which were local units directed by a knight commander of the military order. The encomienda could place the headquarters or residence of the knight commander in a castle or fortress or in a small town which then became the administrative or economic centre in which the rents of the estate and properties relevant to that encomienda were paid and received; it was the habitual residence of the knight commander.

Each encomienda had to support the knight commander and any other knights living there, and to pay and arm a certain number of spearmen, who had to be properly equipped and take part in military actions ordered by their commander. The combined forces from all the encomiendas formed the Army of the Order of Santiago, which answered to the orders of its grand master.

Each year every encomienda was inspected; in effect a census, of people, landholdings, produce and livestock, but also including the stock of arms held within the encomienda and the taxes raised. The details of the Inspection were kept meticulously in ‘El libro de Visitas’ - The Visitors Book. One Visitors Book has been preserved and can be seen at the castle in Segura de la Sierra and gives an incredible insight into life during the Mediaeval period in the Christian part of Andalucia.

The Inspectors were also expected to enquire into the devoutness of the Knights. The Book of Visitors records that, when the visitors inspected the Castle of Segura in 1498, they tested the alcaide of the fortress, Francisco de Zambrano, to confirm he could recite his prayers. Francisco seems to have passed this test but he could not find a copy of the Rules of the Order. He was ordered to find it ‘by Christmas Day’ and had to then read it once a month. Due to the constant absence of the commander, the castles were normally left in the charge of an alcaide who lived in the castle with his family and servants.

Letters preserved at Segura, reveal that both Boabdil and the Catholic Monarchs wrote, entreating the alcaide to help their respective sides during the final reconquest.

In the areas under their rule, the members of the Order took control of the flour mills, olive presses, communal ovens, salt pans and mines and, strangely, cloth-cleansing machines. They were then able to control agricultural output and textile manufacturing. Taxes were extracted based on productivity in the fields and cottage industries, normally paid in kind.

Other revenue for the Order came from land and pasture rental and tolls on rights of way.

Martiniega: This was an annual tax levied on St. Martin’s Day, the 11th November, on the peasants who worked uncultivated land.

Alcabalas: These tolls were charged at the entrance to the town depending on the products heading for the market. The towns could also charge for a person or a beast of burden.

Herbajes: This tax was imposed on stockbreeders who brought their herds up the drover’s routes to graze in the Sierra de Segura. Contaderos collected this tax at various entry points to the encomienda.

Leases: Leases were levied on tenants of certain facilities such as mills, slaughterhouses, salt mines, orchards and housing facilities. For example, one hen per year was charged to use one of the vaults of the old Arab baths in Segura that had been turned into a dwelling.

The economic value of the Encomienda de Segura was the largest in the province of Castile, reaching 2 million maravedies per year. A tenth part of this was given to the prior at Uclés and the rest invested into the encomienda to pay for the soldiers, repairing and constructing facilities and paying for the annual inspections.

It is difficult to convert the 13th - 14th century maravedi into a value of today but between 1256 and 1271, Alfonso X coined maravedi that contained 3.67 grams of silver, worth about 2 US dollars today.

Amongst other duties, the Order was charged with repopulating the land and rather than expel productive Muslim communities, they allowed many to remain. This policy, and that of raising taxes generally, put the Orders into conflict with the Church.

Although it has long been assumed that people during the mediaeval period and the middle ages had no say in their lives or future, the Visitors Book reveals that when a town was taken over, a municipal council was created and all residents were members of it. In Segura, on Sundays, after mass, there was a public meeting where matters of the council were decided and where local magistrates, mayors, scribes and even cowherds, were appointed.

By 1492, the Order of Santiago and its sister Orders of Calatrava, and Alcántara were incredibly powerful, more powerful even than the unifying monarchs, Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile.

In 1499, to strengthen their own position, the rulers obtained permission from the pope to assign to them the administration of the three major Spanish orders – Santiago, Calatrava, and Alcántara. Although the orders still had the right to hold their possessions, titles, and function separately.

The power of the Spanish military orders came to an end during the reign of Charles I (the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V) when the three orders were incorporated into the Spanish Crown. A Council of Orders was formed to oversee the administration of the Orders. The Orders retained only their prestige and many figures involved in the conquest and governance of Spain’s possessions in the New World hailed from these Orders, having discovered a new source of riches; gold, silver and slaves.

Unlike the Templars, who were mercilessly hunted down and persecuted in many European countries because they refused to release their holdings to the respective monarch, the Order of Santiago seems to have acquiesced peacefully.

The Order of Santiago was part of the Spanish Crown until it was suppressed in 1873 when Spain declared the first republic. After the fall of the first republic, the order was re-established though as a nobiliary institute. The order was once more suppressed following the proclamation of the second republic in 1931, which was followed by the Spanish Civil War and the dictatorship of Francisco Franco. Democracy was restored in 1976 and with it the monarchy and the Order of Santiago.

The order continues to this day.