Growing competition between Greeks, Carthaginians and Phoenicians and unrest in the east hastened the end for the Phoenicians

By Nick Nutter | Updated 6 Mar 2022 | Andalucia | History |

Login to add to YOUR Favourites or Read Later

The Phoenicians were the dominant trading partners with the Tartessians and Iberians in Andalucia from the 9th to the 6th centuries BC. Growing competition from Greek traders and then the Punic colony of Carthage, combined with unrest back in Tyre was to prove fatal for them.

Cerro del Villar was founded in the 8th century BC on what was then an island in the delta of the Rio Guadalhorce near present-day Malaga. It became a centre for agriculture and commercial amphorae production with links to the Phoenician trading network throughout the Mediterranean arena. As with most Phoenician settlements the island had access to a natural harbour whilst the Guadalhorce provided a communications highway to the interior.

Only part of the site has been excavated, there is much more to learn, but to date the town plan reveals large residential areas separated by streets. Many of the houses have their own oven and well. All are arranged on a north/south axis and some, with more than six rooms, area arranged around a central courtyard. A few had direct access to the sea and a private jetty via stone steps.

The 7th century BC saw Phoenician trade throughout the Mediterranean at its height and it is during this period that a pottery was established at Cerro del Villar that produced pithoi, amphorae and other large containers. These containers held the products that were shipped inland to the indigenous settlements of Cerro de la Mora, Alhama, and Cerro de los Infantes among others as well as the products to be transported elsewhere via the sea. The containers were themselves exported to other Phoenician settlements on the Andalucian Mediterranean and Atlantic coasts. Recent evidence suggests that the containers were re-used so their 'export' was a by-product of the original trade.

Trade was not all one way. Artefacts found at the site include Ionian cups and ceramics from the Greek island of Samos and Etruscan amphorae and bucchero from Italy.

Agriculture was an important part of life. Finds of numerous stone grinders indicate that wheat was ground on an industrial scale and there is evidence of other crops such as barley, peas, beans, lentils and peaches. In the early days of the settlement, wine was imported from the east. Vines were planted at the site that eventually produced grapes from which wine was made that was then consumed locally as well as exported.

In one structure fishing equipment, hooks, lead weights, and harpoons were found whilst in another were piles of Murex shells. These finds indicated fishing and a dyeing industries. The prized purple dye was made from the Murex mollusc. There were also indications that the fierce fish sauce - garum, was manufactured at the site.

Cerro del Villar was clearly a thriving trading centre with both indigenous communities in the interior whilst maintaining maritime links with the wider Mediterranean.

The 7th and 6th centuries BC was a troubling time for Phoenicians. Although we think of them today as a group and give them a name it is highly unlikely that they thought of themselves in those terms. It is more likely that they identified with their home city, Tyre, which had sent out merchants to concentrate on the western Mediterranean. Byblos, other 'Phoenician' cities in Lebanon, concentrated on the inland trade route to Syria and Mesopotamia and the southern route to Egypt. Although the home towns cooperated with each other, especially in the dispersal of exotic goods brought back by their overseas traders, they were highly competitive. Overseas colonies were expected to pay tribute back to their home cities.

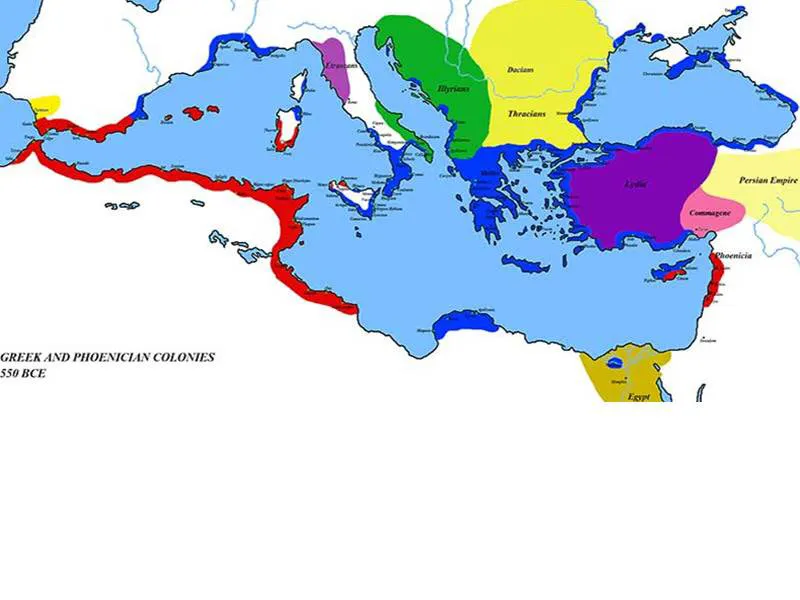

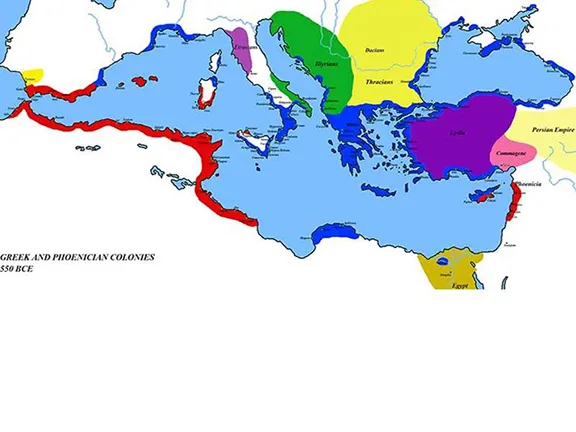

One group of merchants from Tyre established a colony at Carthage on the Tunisian coast opposite Sicily around 814 BC. This was a deliberate attempt to keep control of trade in the central Mediterranean. The Greeks, in particular, were establishing their own trading posts, at first in the Adriatic with Corcyra on Corfu about 733 BC. Then they expanded to Italy and Sicily. The Greek settlement at Syracuse on Sicily was established as early as 733 BC.

Carthage grew into a sizeable city and its population started to found its own colonies on the coast of North Africa. Carthage began to challenge Tyre both in size and influence and, because they were prepared to defend their trade routes from the Greek threat, began to build an armed presence in the central Mediterranean.

Back home, in Tyre, surrounding civilisations jealously coveted the wealth generated, and the exotic goods carried, by the merchants. Egypt led sporadic raids against the city but the main threats started in 727 BC when the Assyrian, Shalmaneser V, laid siege to the city for 5 years. A period of relative peace lasting 150 years allowed the Tyrhenians to rebuild their trading economy. This period is clearly reflected in the increased activity at overseas settlements. Then the proto Babylonian empire led by Nebuchadnezzar II decided they should have a slice of the pie and laid siege to Tyre between 586 and 573 BC. They eventually persuaded Tyre to pay an annual tribute. A shaky status quo lasted until 539 BC when the city was conquered by the Achaemenid Empire, the first embryonic Persian Empire. They held the city until Alexander the Great razed it in 332 BC.

The Tyrhenians abroad lost their link to their home city and effectively became stateless. From 573 BC they also had less incentive to trade with their former city back in the Lebanon. The emerging Carthaginian Empire was poised to take advantage in the western Mediterranean. The Phoenician settlements in Andalucia had an option, become part of the Carthaginian sphere or cease trading.