The discovery of silver in the Sierra Almagrera in Cuevas del Almanzora municipality, Almeria, Andalucia caused silver fever in the 19th century

By Robert Vernon | Updated 25 Aug 2022 | Almería | History |

Login to add to YOUR Favourites or Read Later

Jarosite Crystal

The Sierra Almagrera mountain range runs for 8 kilometres north-eastwards from the fishing village of Villaricos, Almeria. At its broadest point near the inland village of Los Lobos, it is 1.5 km wide. The Sierra is composed of micaceous schist, generally a soft dark rock that glistens with mica, interspersed with hard pods of white quartzite.

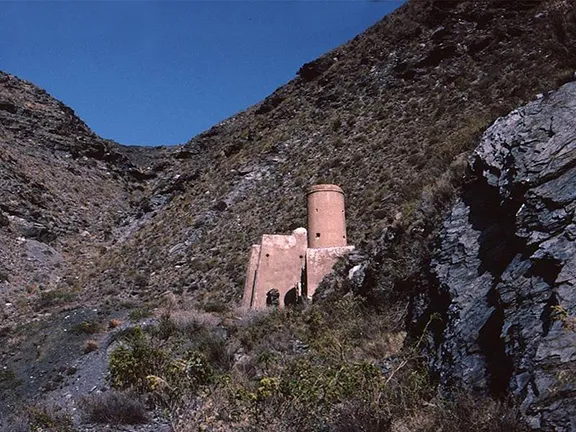

Barranco Jarosa Mine

The mountains are crisscrossed with mineral veins that contain predominantly lead and silver, as well as zinc, copper and iron, and occasional traces of gold. One mineral in particular, Jarosite, has made the area famous. It is a yellowish-brown iron-rich mineral and was first described in 1852 after its discovery in the Barranco Jarosa, an intensely mined area immediately to the east of Los Lobos. Jarosite has come under the spotlight again in recent years when NASA discovered traces of it on Mars. The minerals were first mined intensely in Roman times, mainly for the lead and silver. Lead was of particular value to the Romans and was used in plumbing and also to make ‘potent’ cosmetics. To support these operations the Roman settlement of Baria was founded, at the mouth of the Rio Almanzora, at the southern end of Villaricos. Recent archaeological excavations there have revealed an extensive settlement. When mining was at its peak in the 19th century, Roman mine workings were frequently encountered and walking around the mountains today, some of the shallow and narrow Roman workings can be identified on hilltops following the line of a mineral vein.

Following the Roman activity little seems to have been mined in the Sierra Almagrera, until a chance discovery was made in 1839. According to the story, ore was discovered by a poor weaver called Valentin from Cuevas de Almanzora, who was out shooting rabbits, he observed anomalies in the rock and concluded that the ground must contain ore. He dug around in the Barranco Jaroso and quickly found a lump of ore. It was beyond his means to test it, so he took it to a smelter in Granada, where it was identified to be silver-rich lead. Being penniless, he brought his discovery to the attention of Soler, a rich fellow townsman, who eventually with fellow adventurers established the El Carmen mine in the Barranco. The mine proved exceedingly rich, and so Soler quickly established further mines in adjacent areas. This trend continued and the area became famous worldwide for its richness throughout much of the 19th century. The ore was smelted to release the metal, the smelters were located around Los Lobos and Villaricos. Flues from the smelters can be seen snaking around the sides of low coastal hills to the north of the latter village. Towards the end of the 19th century, as the mines were getting to a deeper level, water was getting into the workings, and so elaborate pumping schemes were introduced. However, by the early 20th-century mining activity was starting to dwindle. This was due to three main reasons, firstly pumping water from the workings was becoming difficult and expensive; secondly, the price of lead ore was very low, so Spanish lead mining frequently gave low profits if any; thirdly the world metal market was being swamped by a glut of lead ore from places like Broken Hill, Australia. So with this pressure, mining in the Sierra came to a standstill in 1912.

However, there was a final phase of mining. In 1944 the Spanish government issued a decree for a company to be established to work the mines for national interests. On the 8th November 1945, the Minas de Almagrera S.A. was constituted. The company established its headquarters at El Arteal at the southern end of the range, below the Barranco Frances, which had also previously been intensely mined. The remit of the company was to take over mines drainage, and to intersect and prove and work the mineral veins. To achieve the first objective, the Santa Barbara Adit (tunnel) was driven a total distance of just over 4 kilometres in a north-easterly direction from El Arteal following the spine of the Sierra Almagrera. It accommodated a double-track railway system over some of its length that fed directly to an ore-dressing mill. The mill housed an ore separation technique, known as oil-flotation, a method that was in its infancy in 1912. Its advantage was that the metallic ore could be extracted profitably from relatively poor grade vein material. In addition, offices, workshops, electrical installations were constructed, as well as bathhouses for the miners, and rows of barracks to house the workforce and their families. It is believed mining ceased at El Arteal sometime in the early 1960s.

A visit to the Sierra Almagrera today reveals a unique mining landscape. To operate a mine, firstly the miners would have to lease a concession from the landowner, and this would have to be formally registered with the Spanish Governments Department of Mines. In the Sierra, the Barranco Jarosa and Frances contain the greatest concentrations of concessions. Invariably the mineral veins were accessed by deep shafts, as there wasn’t often sufficient distance to drive a tunnel within the concession. The shafts were essential for accessing the ore and providing ventilation. Consequently, shafts are everywhere and usually unprotected so a visitor to the Sierra must constantly bear this in mind. Even the highest point, Tenerife (368m) has an unprotected open shaft within a few metres of its concrete marker. As mines got deeper, hand-winding, or the use of mules, was replaced by steam power, and so stone headgears and houses for steam engines are scattered around the mountainside. The introduction of steam-powered machinery provided another problem, where to get water for the boilers? This was overcome by constructing channel systems to catch rainwater, and the water was then fed into large cisterns. The routes of the channels now form a network of footpaths that skirt the highest peaks. There is still one steam winding engine in existence on one of the mine sites, near to the Barranco Jarosa. It was manufactured by the Reading Iron Works, of England, and was probably brought into the area in the 1870s. Recently, the Junta de Andalucia conserved the engine manufactured by the Reading ironworks, Reading, United Kingdom, in situ.

Areas like the Barranco Frances, just above El Arteal, still bear testament to the intensity of mining. A stone wall still encircles the mine yard, which in its day would have housed workshops, carpenters, blacksmith, storage and ore treatment facilities. Flues lead away from this area from old hearths and steam-operated facilities. An adjacent two-storey building probably housed offices and barracking.

At El Arteal, where final mining operations took place, there are also considerable remains. These include a transformer house with the company logo still attached, mine offices and general mine buildings. Adjacent to the ornate portal to the Santa Barbara Tunnel, which lies just south of the main site, there are two round miners bath-houses which have recently been converted into living accommodation. About 60m in front of the portal there is a steep drop to the site of the flotation mill. To the south lies the recently landscaped tailing dump, now used for growing lettuces!

In the surrounding area, there are other mines like those at Las Herrías and the Tres Pacos, near Cuevas de Almanzora, for example. At the latter site, the iron ore had to be roasted, or calcined, to make mineral separation easier. Five circular calciners dominate the site as well as mine offices and workshops. The ore from this site was transported by aerial ropeway to the coast, just to the north of Villaricos, to be loaded onto ships. To get there, the ropeway had to cross the Sierra Almagrera and there is still evidence of its route, including stone support towers that look similar to stone headgears, and a deep cutting through the ridge.

It cannot be emphasised too much that a visit to the Sierra Almagrera must be done with extreme caution because of the number of open shafts, some of which are even located in the middle of footpaths. It is not a place to take small children or animals.

Vernon, Robert. (2010). Notes about the lead mines of the Sierra Almagrera, Almería, Spain

For information about Mining in the Sierra Almagrera and Las Herrerias