The Battle of Navas de Tolosa is seen as the turning point in the reconquest. Christian forces established themselves south of the Sierra Morena.

By Nick Nutter | Updated 11 Apr 2023 | Jaén | Museums |

Login to add to YOUR Favourites or Read Later

Battle of Tolosa Monument - La Carolina

During the 13th century, attitudes to war were different to that of today. For many populations in Europe, war was a fact of life. You were either oppressed by marauding bands and armies or you were the oppressor. Between 1200 and 1300 AD, not a decade went by without a war being fought somewhere in Europe. For the victorious oppressor, the rewards could be considerable, honours, land and wealth from booty. Those were the main motivations behind the invasion of al-Andalus that led to the Battle of Navas de Tolosa in 1212. A battle heralded by the victors and historians since, as the beginning of the end for al-Andalus.

Site of the Battle of Navas de Tolosa

For five hundred years, al-Andalus in the Iberian Peninsula, the land ruled by Muslims from North Africa and the Middle East, had been a magnet for invaders. Al-Andalus was fabulously wealthy, it had huge tracts of fertile land, much of it irrigated using techniques unknown at that time to the rest of Europe. It had mosques and palaces filled with treasures and an income based on overseas trading that was unrivalled anywhere. Goods traded between the Arab world of al-Andalus, Africa, the Middle East and Europe included slaves, spices, perfumes, gold, jewels, leather goods, animal skins, and luxury textiles, especially silk, olive oil and, despite the Muslims being nominally teetotallers, wine. Students and their tutors in universities in Granada, Cordoba and Seville had a repository of knowledge of medicines and surgery, plants and animal husbandry, navigation and map making, metal working and mechanics amassed over two thousand years that was unsurpassed anywhere else in the world at that time, apart from perhaps China. In other words, it was a plum ripe for picking.

Christian cavalry saddle

Since the Muslim invasion of Spain in 711 AD, the Christian forces from the north, had been slowly regaining territory they had lost. Some seasons they gained a little, some years they lost a little but after 500 years, the Muslims were still firmly in control of the south of Spain. It could be argued that, by the 13th century, the Muslims had a legitimate claim to the land. They had been there a long time. The population was for the most part settled despite there being cohabiting religions, Islam, Christian, and Jewish. Many of the Christian families had married into Muslim or Arabic families and vice versa. They had improved the land they occupied, and they had improved the wealth and health of the populace.

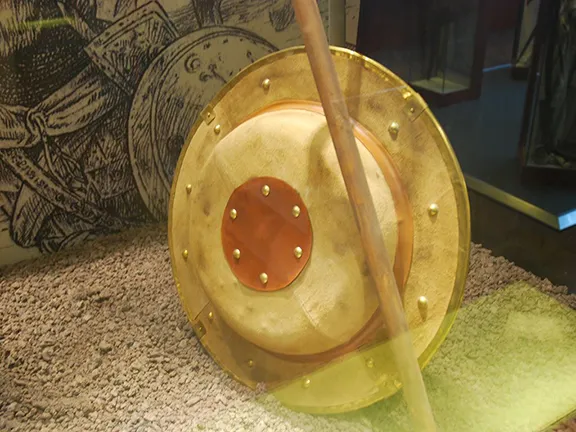

Knights shield

The justification broadcast by the monarchs of the various principalities in Christian occupied Spain for attacking al-Andalus was that they were ‘saving’ the Christian population of al-Andalus. In reality, they could not give a fig about anything apart from increasing their own wealth and power. We know this because, even after the Battle of Navas de Tolosa in 1212 and its aftermath, the Christian forces abandoned most of their gains in al-Andalus. They had no intentions of providing administrators to control the territory they had gained south of the Sierra Morena mountains, nor the troops required to defend it. We also know the composition of the Christian forces, many of whom could not have had any motive other than plunder.

Muslim cavalry saddleq

Alfonso VIII of Castile initiated the invasion and was joined by King Pedro of Aragon, soldiers from the Kingdom of León and King Sancho of Navarra. To legitimise the attack, the archbishops of Toledo and Narbonne joined the throng. Knights from the Orders of Calatrava and Santiago, Knights Templar and Knights Hospitaller turned up along with troops from Portugal, France and Occitania (an area of southern Europe that encompassed parts of Spain, France and Italy). To bring such a force together, Alfonso had approached Pope Innocent III and asked him the call a crusade. Alfonso had two reasons for wanting a crusade, to attract forces from outside Spain and to prevent his kingdom of Castile from attacks by his enemies, the Kings of León and Navarra. It would have been most unchristian of those kings if they had taken advantage of Alfonso’s absence. Both decided they had more to gain by forming a temporary alliance with Alfonso and joined the crusade.

Pope Innocent III had little reticence about calling a crusade. He also had motives other than ridding the world of Muslims. By the 13th century, crusades had been a regular occurrence for two hundred years, the various military and religious orders, Santiago, Calatrava, Templars, Knights of Jerusalem et al, had become powerful by accumulating land and wealth, mainly donated to them by grateful sovereigns. By 1212 there were over twenty knightly orders, and their power was beginning to compete with that of the Pope himself. Any excuse to whittle down their numbers was good news for the Pope. The crusaders themselves were also in favour of a crusade in Spain. It is far easier and quicker to travel to Spain than it is to travel to the Holy Land and the potential gains were much greater. The crusading army assembled at Toledo.

Muslim shield

With the stage set, Alfonso and his band set off south, heading for the only natural break, the Despeñaperros Pass, in the Sierra Morena, a 500 kilometre chain of mountains that runs west to east forming a natural barrier between Andalucia to the south and the rest of Spain to the north. Guarding the northern end of the pass were two towns, Calatrava le Vieja and Alarcos, that were soon dispatched. At the southern end of the pass, Castro Ferral, or Ferral Castle, near the village of Santa Elena, was abandoned by its defenders and occupied by Christian forces.

Whilst Alfonso was organising his army, the Almohads in al-Andalus were busy preparing their forces. Al-Nasir raised an army in Marrakesh and crossed the Straits of Gibraltar to support the Muslim forces already in al-Andalus. Modern research indicates that the size of the competing armies was far smaller than that claimed by the two sides at the time.

Alfonso talks about 62,000 men divided up into 2,000 knights, 10,000 horsemen and 50,000 infantry. The Muslim chronicles claim the Almohads gathered 600,000 men. In reality, the crusading army probably had 12,000 combatants in total and the Almohad army about 20,000. It is worth looking at the logistical problems faced by the opposing sides.

The Almohad Caliphate had an effective administration system that allowed them to move large armies within its territories with relative ease. Along each route there were encampments and supply points. Even so, moving an army from Marrakesh to the far north of Jaén province involved the use of 200 ships to cross the Straits of Gibraltar and it took two months to move that army up the peninsula.

The Kingdom of Castile had no such infrastructure. The army was expected to feed itself. A large army could be compared to a swarm of locusts, consuming everything in its path, food, crops, fodder and water irrespective of whether they were in friendly or enemy territory. It is enough to look at the daily consumption of a warhorse: 14 kilos of fodder, 5 kilos of oats and 35 litres of water. A contingent of 1,000 horsemen had a daily requirement of 1,620 tons of supplies just for the horses. That amount required 3,200 wagons that created a wagon train 20 kilometres long, a full days march.

Alfonso had other problems such as controlling his troops, particularly the French and European contingents. Following the taking of Calatrava la Vieja, Alfonso had been lenient in his treatment of the defeated Jews and Muslims, a policy that did not sit well with the foreign Knights.

Despite the supply problems, Alfonso’s crusading army was better equipped than the Muslim forces. His heavy cavalry was more than a match for the much lighter armoured Muslim horse troops and devastating against the Muslim infantry.

The two armies met near the present day village of Santa Elena in the province of Jaén in Andalucia on the 16th July 1212, just south of the Despeñaperros Pass . The crusaders won the battle with the loss of 12,000 troops whilst the Almohad army lost 20,000 soldiers, many after the battle when Alfonso’s troops went berserk and pursued and killed the fleeing Muslims.

Following the battle Alfonso moved on to take the castles of Navas, Vilches and Baños de la Encina. He entered the nearby town of Baeza, from which the inhabitants had fled to adjoining Úbeda, and then laid siege to Úbeda, eventually slaughtering or enslaving up to 60,000 of the inhabitants.

The Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa was the first major battle of the reconquest and pushed the front line, or frontera, south to the Sierra Morena mountains. In that respect Alfonso did gain a victory. He did not however have enough support to administer and defend the territory he had gained south of the mountains so was forced to abandon it. It was to be his grandson, Ferdinand III, who in 1236, next crossed the Sierra Morena mountains to take up the fight.

Out of all those involved, it could be argued that the Pope benefitted most. The Knightly orders were severely weakened during the campaign with the loss of Pedro Gómez de Acevedo (bannerman of the Order of Calatrava), Alvaro Fernández de Valladares (commander of the Order of Santiago), Pedro Arias (master of the Order of Santiago) and Gomes Ramires (Portuguese master of the Knights Templar and simultaneously master of León, Castile and Portugal). Ruy Díaz (master of the Order of Calatrava) was so grievously wounded that he had to resign his command.

The Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa museum is on the site of the battle near the village of Santa Elena in Jaén province. A modern museum, it displays a balanced and reasoned view of the battle, the motivations of the participants, compares their military equipment and illustrates the political attitudes of the time.

Information is in Spanish and English and you will be issued with an audio device that tells the story in Spanish, German, French and English.

The Battle of Navas de Tolosa Museum opening times and prices