Soon after Italy entered WWII, Italian Regia Marina started underwater operations designed to sink allied shipping at Gibraltar. This is their story.

By Nick Nutter | Updated 5 Dec 2022 | Gibraltar | History |

Login to add to YOUR Favourites or Read Later

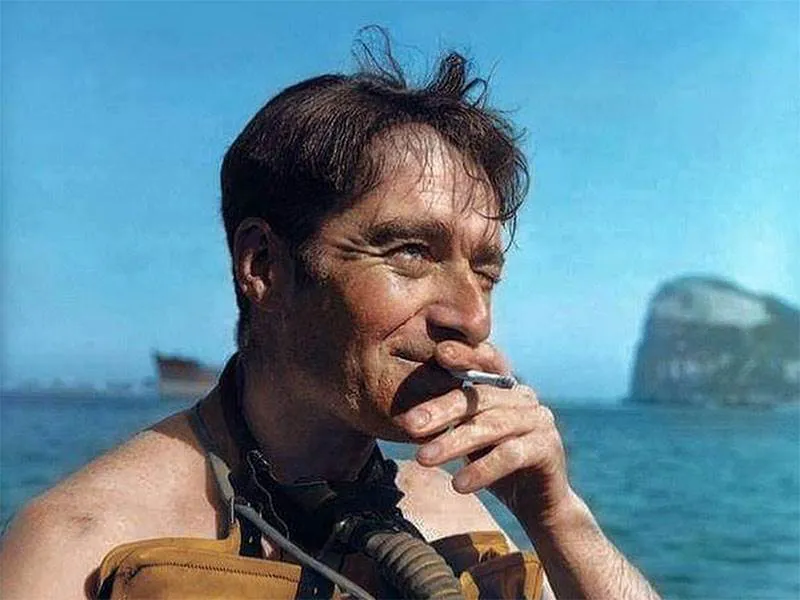

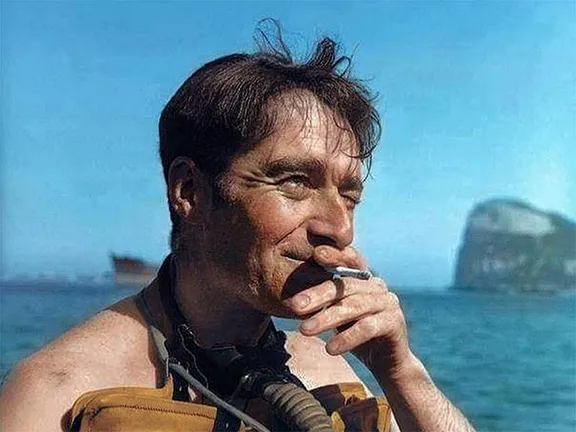

Lionel 'Buster' Crabb

During WWII the Italians devised a daring plan designed to threaten Allied Shipping in Gibraltar Bay off the shores of neutral Spain. The operation was conducted with all the panache associated with the Italians.

The Strait of Gibraltar

The Strait (sometimes Straits) of Gibraltar is 58 km long and narrows to 13 km in width between Point Marroquí in Spain and Point Cires in Morocco. The Strait’s western extreme is 43 km wide between Cape Trafalgar to the north in Spain and Cape Spartel to the south in Morocco, and the eastern extreme is 23 km wide between the Pillars of Heracles, the Rock of Gibraltar to the north and one of two peaks to the south: Mount Hacho (held by Spain), near the city of Ceuta, a Spanish exclave in Morocco; or Jebel Moussa (Musa), in Morocco.

Gibraltar from the air

The 1,400 metre high, 2.8 kilometre long, 1.2 kilometre wide, lump of Jurassic limestone that makes up the Rock of Gibraltar, is a British Overseas Territory. Viewed from space, the Rock resembles a lady’s tear shaped earing, suspended in the Gibraltar Strait below a narrow isthmus that attaches it to mainland Spain at a town called La Línea de la Concepción.

With the fall of France in June 1940, Gibraltar became the only allied territory on mainland Europe. Gibraltar controlled virtually all naval and merchant traffic into and out of the Mediterranean Sea from the Atlantic Ocean, an essential part of Britain’s supply lines with Crete, Malta, her armies in Egypt, and, via the Suez Canal, the Far East. This 6 square kilometre (6.8 square kilometres now due to the reclaiming of land on the western flank of the Rock) piece of land, has a deep harbour on its western side that was defended by guns positioned on the heights to the east. The harbour is protected by three moles, the north mole, south mole and between the two, a detached mole, each with its own gun positions. The only two entrances to the harbour are between the detached mole and the north mole and the detached mole and the south mole, each passage being about 150 metres wide.

Eight kilometres directly west of Gibraltar harbour is the Spanish town and port of Algeciras. Between the two is a deep-water bay variously called Algeciras Bay or Gibraltar Bay, depending on which nation produced the map. Gibraltar Bay is entered from the Strait to the south and was and is, an important, sheltered anchorage for ships waiting to enter Gibraltar harbour itself.

After June 1940, Gibraltar faced four potential enemies: Vichy France to the north of Spain and Vichy French occupied territories just across the Strait in Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia; Germany itself; Italy, who had entered the war on the 10th June 1940, allied to Germany; and Franco’s Spain who were ostensibly neutral but leaned towards the Axis. Franco considered it a matter of national honour that Gibraltar be retaken and restored to Spain, preferably by Spanish armed forces.

The Moles, south, detached, north

After Italy joined the Second World War, Mussolini considered the Mediterranean Sea his own ‘pond’ or in Roman terms ‘Mare Nostrum’ and was confident he could defeat the Royal Navy at Gibraltar and Suez. With four battleships, two newly built 35,000 ton super-dreadnoughts each capable of speeds of 30 knots and armed with nine, fifteen inch guns, seven heavy cruisers, twelve light cruisers, ninety destroyers, dozens of fast motor-torpedo boats and over 100 submarines, he certainly had the forces to do so.

During the First World War, the Italian Regia Marina, one of the fleets of the allied Entente, had gained a reputation for innovative submarine warfare and continued to develop weapons for use underwater between the wars.

By June 1940, Decima Flottiglia MAS, the Italian navy’s assault craft branch had developed weapons and tactics that would revolutionise underwater warfare; explosive motorboats, midget submarines, leech and limpet mines, delayed action mines and manned torpedoes.

Decima Mas diver

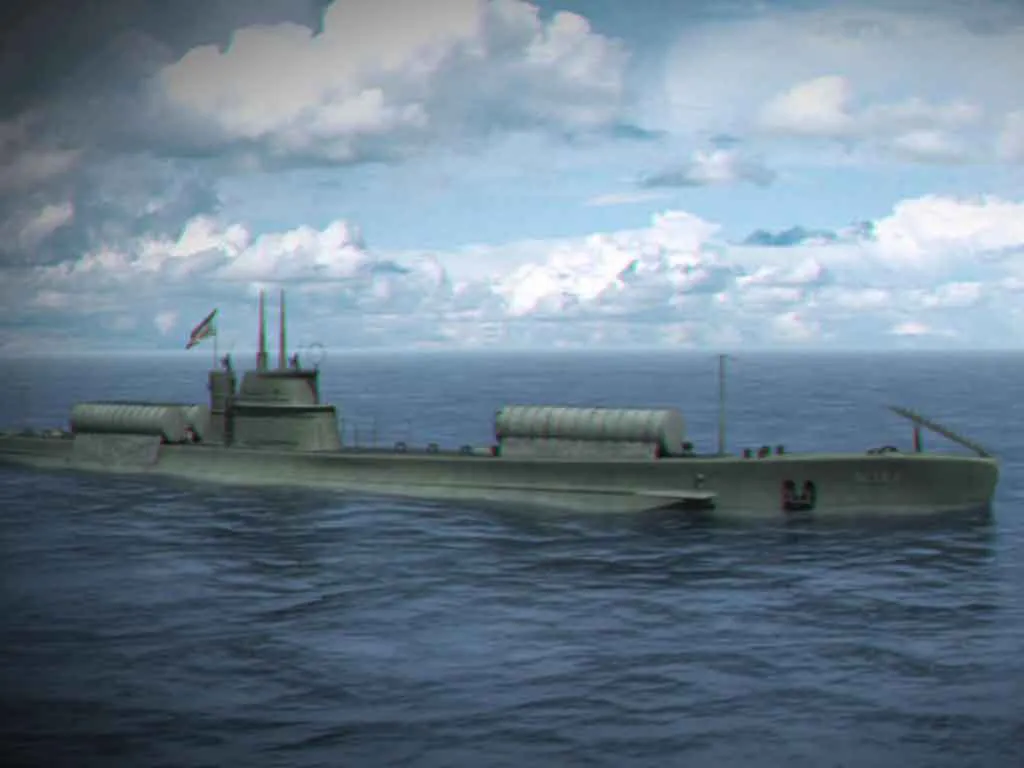

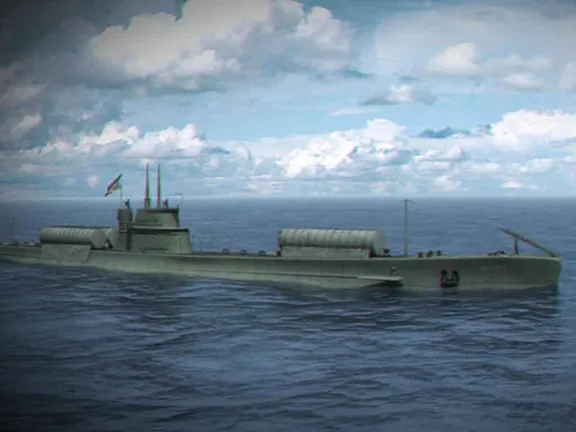

At 2am on the 30th October 1940, the Italian Adua-class submarine, Scirè, commanded by Junio Valerio Scipione Ghezzo Marcantonio Maria Borghese, surfaced at the north end of Gibraltar Bay, in the commercial anchorage near Puente Mayorga, opposite the town of La Línea and at the mouth of the Rio Guadaranque, only 3 kilometres from the British warships anchored in Gibraltar harbour. Its crew had painted the superstructure of the submarine with the silhouette of a trawler with its bow pointing towards the submarine’s stern in a brilliant example of the new technique of ‘distractive camouflage’.

Scirè, based at La Spezia which is on the northwest coast of Italy on the Ligurian Sea, between Genoa and Pisa, had silently passed Gibraltar the previous night and had spent the day hanging around at 70 metres depth in the Bay of Tolmo between Algeciras and Tarifa. After dark, the submarine slowly made its way back into Gibraltar Bay. The crew were operating a silent routine, wearing rope soled sandals, speaking in whispers and wrapping their tools in cloth to prevent any clanging. Overhead, on the surface, motorboats, trawlers and a British destroyer were unaware of the presence of Scirè with a precious cargo.

On deck were three canisters, one where the forward gun should have been, in front of the conning tower, and two secured to the aft deck. Six men slipped out of the hatch, all dressed in dry suits to protect them from the cold water. They unloaded the canisters to reveal three, 2-man chariots.

The Italian name for the chariots was Siluro a Lenta Corsa or ‘slow speed torpedo’. Each was 6.7 metres long and weighed 1.3 tons. To the rear was an electric motor and propellor giving the torpedo an operational duration of 6 hours and a top speed of 3 knots. The front of the torpedo was a detachable warhead containing 300 kilograms of explosive and a time fuse. Two men sat astride the torpedo, the front man was responsible for navigation and steering, the rear man’s duties included cutting through anti-torpedo nets and helping to suspend the warhead beneath the target ship. This was achieved by fixing two G clamps clamps to the bilge keels beneath the waterline. A rope was run between the clamps and the warhead was suspended from the rope by a ring welded to the warhead casing. The chariots were notoriously difficult to steer, and on a training exercise, one operator had uttered the Italian expletive, ‘maiale’, in English, pig or hog. The nickname stuck and the Italians referred to their underwater chariots as ‘maiale’ thereafter.

Each of the swimmers was equipped with fins, mask and a breathing apparatus. The breathing apparatus was what is known as a ‘rebreather’. The kit comprised a rubber bag filled with soda lime, strapped to the diver’s chest and an oxygen bottle slung below the bag. A tube led from the bag to a mouthpiece. In shallow waters, a diver only uses about 25% of the oxygen in the air that he is breathing. The oxygen is converted to poisonous carbon dioxide. As the diver exhales, the carbon dioxide rich air passes into the bag where the gas is absorbed by the soda lime. The oxygen bottle delivers a small amount of oxygen to replace the carbon dioxide and this oxygen enriched air is then inhaled by the diver. A huge benefit of rebreathers over a conventional open circuit breathing system was the lack of exhaust bubbles that could easily betray the diver to a watcher on the surface.

The three maiales were launched from the deck of Scirè that then submerged to return to La Spezia. The three crews were; Lieutenant Luigi Durand de la Penne and Emelio Bianchi, Major Teseo Tesei and Petty Officer Alcide Pedretti, and Gino Birindelli and Damos Paccagnini.

The mission did not go well. Durand and Bianchi were depth-charged by a motorboat, which sank their maiale. The two men abandoned their breathing apparatus and swam 3.25 kilometres to the Spanish shore where, at 7.30am, they met up with an agent, retired naval officer and engineer, Giulio Pistono, at a prearranged rendezvous on the coast road between La Línea and Algeciras. Pistono had been granted diplomatic status and was attached to the Italian Consulate as ‘Chancellor’.

The second pair, Tesei and Pedretti, managed to get within sight of the North Mole before both their breathing apparatus started to play up. They detached the warhead and motored towards the lights of La Línea. At 7.10am they landed at La Colonia, the western district of La Línea, opened the flood tanks of their maiale and turned it to the southwest to sink in open water. Unfortunately for the Decima Flottiglia MAS, the maiale did not sink and it beached itself on Playa de Poniente at La Línea where it was recovered by the Spanish and taken away for examination. The technology and specifications of the maiale filtered through to the Germans and by subversive means, to British Naval Intelligence.

Tesei and Pedretti made it to the rendezvous point to join Pistono, Durand and Biachi. The four frogmen were successfully smuggled to Seville and flown back to their base at Caserma del Muggiano, La Spezia, in Italy.

Gino Birindelli and Damos Paccagnini had more success. They managed to penetrate Gibraltar’s harbour and get within 70 metres of the battleship, HMS Barham. Their craft suffered a technical problem and became immobilised on the bottom of the harbour. At the same time, Paccagnini’s rebreathing kit failed, and he had to make his way to the surface where he was picked up by a British boat patrol. Birindelli set the timer on the warhead and attempted to swim to the Spanish shore but severe cramp forced him to emerge and climb onto the North Mole. There he mingled with Spanish dock workers and hid himself on a cargo ship called the Sant‘ Anna. He was discovered by the crew who informed him they were still waiting for clearance from Contraband Control before any crew members could leave the ship. As Birindelli was offering the crew a 200 peseta bribe, a British sailor appeared and asked if Birindelli was part of the crew. He hesitated and the sailor became suspicious and returned shortly with two policemen who arrested Birindelli and took him for questioning by a Naval Lieutenant. Birindelli produced his Italian identity card and the Lieutenant passed him on to a Commander. At about this time, the warhead from the maiale exploded creating a huge gout of water, superficial damage to the Barham and panic within the dockyard. Birindelli and Paccagnini became prisoners of war.

As a result of these actions, Gino Birindelli received the Medaglia d'Oro al Valor Militare, his second, Damos Paccagnini received the Medaglia d'Argento al Valore Militare. Gino Birindelli went on to become an Italian admiral and chief of the fleet of the Italian Navy. Borghese received the Medaglia d'Oro al Valor Militare, despite the mission's overall lack of success.

In an allowed letter, ostensibly to his family in Italy, but in reality to Decima Flottiglia MAS at La Spezia, Birindelli urged ‘his brother’ to make another effort to obtain his ‘university degree’ ‘If at first you don’t succeed, try and try again. If one makes the proper preparations, one finds the difficulties are not insuperable’.

Decima Flottiglia MAS got the message loud and clear and in May 1941, they returned to Gibraltar.

Italian submarine carrying maiale canisters

This time, instead of travelling the whole way from La Spezia to Gibraltar by submarine, eight frogmen were sent overland to Cádiz. In June 1940, an Italian tanker called the Fulgor had been interned there. Pretending to be representatives of the owners and members of the crew, the frogmen were permitted to board the ship. On the 23rd May, 1941, Scirè, still commanded by Borghese, berthed near the Fulgor. The submarine crew, unbothered by the Spanish authorities, used the Fulgor as a supply ship, restocking their submarine with fresh food and allowing the crew to have showers and relax on board. Meanwhile, an agent from the Italian Consulate in Algeciras provided the Scirè and the frogmen with intelligence from a recent reconnaissance of the shipping in Gibraltar harbour.

At midnight on the 25th May, Scirè surfaced in Gibraltar Bay and launched three maiales. Their targets this time were in the commercial anchorage because the defences on the moles and surrounding the harbour had been improved and the three capital ships they had hoped to attack, the battlecruiser Renown, aircraft carrier Ark Royal and the cruiser Sheffield, had been detached to the North Atlantic to help track down the German battleship, Bismark.

Technical problems with the maiale and rebreathing kits once again prevented the successful prosecution of the mission. All six frogmen abandoned their maiale and swam to the Spanish shore where they were picked up, taken to Seville and flown home on a Linee Aeree Transcontinentale Italiane (Italian Transcontinental Airlines) Savoia-Marchetti SM.83 tri-motor aircraft.

Undeterred, Decima Flottiglia MAS returned on the 20th September 1941. The May operation had proved the effectiveness of the ingress and egress method and the same ruse was used again. The frogmen were transported to the Fulgor in Cádiz where they boarded the submarine Scirè for transportation to Gibraltar Bay. Three maiales were launched. This time the Italian operation was remarkably successful. The 2400 ton Shell oil storage vessel, Fiona Shell, was blown in half and sunk. At 8.43am on the 21st September, the 15,800 ton naval tanker, Denby Dale blew up and half an hour later, the 10,800 ton freighter, Durham, was also sunk.

The six frogmen swam ashore. Rumours later reached Defence Security on Gibraltar that at least some of the frogmen had been detained by Spanish carabineros and later released into the custody of Giulio Pistono. All six successfully returned to La Spezia via Seville.

The success of the September operation gave the Italians an idea. Why transport men and the maiales all the way from La Spezia when they could establish an operational base on Gibraltar Bay itself? So was born Operation Ursa Major.

Algeciras from Gibraltar

Giulio Pistono already owned a house called Buen Retiro in Pelayo, a small village between Algeciras and Tarifa. The Italians purchased another property, at 98, Avenida de Espana, La Colonia, La Línea with good views over Gibraltar’s commercial harbour, the North Mole and the Coaling Arm. Then a member of the Decima Flottiglia MAS, Antonio Ramognino who had a Spanish wife called Conchita, rented the Villa Carmela which was situated on a small hill alongside the Arroyo Cachon at Puente Mayorga on the north side and overlooking Gibraltar Bay and the western side of ‘The Rock’ including the harbour and anchorages. The rental was organised through a Spanish estate agent who was acting on behalf of the villa’s, ironically, Gibraltarian owner, one J.L.B. Medina, who had been evacuated to Madeira. Ramognino and Conchita immediately undertook some renovations that included a new window behind which they installed a telescope and binoculars to survey Gibraltar Bay and sleeping arrangements for ‘guests’.

The Olterra

A key part of the operation was an interned ship, the tanker Olterra, that was moored inside the breakwater at Algeciras, south of Isla Verde, directly across the road and under the very eyes of the British Consulate.

Built in 1913, on Tyneside in the UK for a German company, the tanker Osage was sold to the Standard Oil Co, in New York in 1914 and renamed Baton Rouge. In 1925 she was again sold, this time to the European Shipping Co Ltd of London and renamed Olterra. As the Olterra she passed through the hands of the British Oil Shipping Co Ltd and in 1930 was bought by Andrea Zanchi in Genoa. On the 10th June 1940, when Italy declared war on France and Britain she found herself in Gibraltar Bay. The shipping records of the builders, Palmer’s Ship Building and Iron Co Ltd, indicate that she was sabotaged and sunk by British commandos close to the Algeciras shore.

A more likely scenario is given by Paul Kemp in his book ‘Underwater Warriers’. “Olterra had been scuttled by her Italian crew on the outbreak of war” In early 1942, Lieutenant Licio Visintini, last heard of in September 1941 when he led the maiale that sank the Denby Dale, was put in charge of a team of commandos disguised as Italian civilians. Under the pretext of repairing and selling the Olterra to a Spanish buyer they raised the ship and towed it into Algeciras harbour. Again according to Paul Kemp, “, [the Olterra] had been refloated by the Spanish and secured inside the breakwater at Algeciras. A guard consisting of a corporal and 4 privates of the Guardia Civilia was placed on the ship to prevent any unauthorised personnel boarding her. In March 1941 members of Olterra's original crew, including Paola Denegri, the chief engineer, reboarded the ship to act as a care and maintenance party.” The Olterra found herself moored almost directly beneath the windows of the British Consulate in Algeciras.

The ship was guarded by a Spanish military guard who were stationed aboard. Their task was to ensure nobody, other than the crew, could board the vessel without a special pass. Since March 1941, the crew had consisted of a rag tag bunch of Italian sailors gathered from other interned ships. The captain of the Olterra, Domenico Amoretti, had found the time and opportunity to marry a local girl and lived ashore at Villa Victoria, Secano, near Algeciras.

Visintini replaced the crew already on the Olterra with his own seamen and technicians. Part of their training involved learning how to look, walk, talk and dress like undisciplined Italian merchant seamen. They were sent to live aboard a cargo ship moored at Livorno where they morphed into unshaved, scruffy characters, wearing old clothes, and spitting on deck between every sentence uttered.

The new ‘crew’ travelled to Spain using fake names, identity cards and seamen’s log books where they joined the Olterra, ostensibly to effect more repairs. An observation post was created in a cabin in the forecastle, whilst deep within the ship the holds were converted into workshops for the assembly and maintenance of the human torpedoes. A compartment in the forepeak was converted into a water tank, deep enough to test the maiales for water resistance and trim them.

The crew’s greatest challenge was to provide a way for the maiales and their crews to leave the Olterra and return after the mission. The ship was careened, that is, whilst alongside, ballast tanks on one side of the ship were filled with water so that the ship leaned over. A canvas awning, spread over the exposed side of the ship, sheltered the working party from the sun. It also hid their activity from prying eyes, including those watching from the British Consulate balcony, almost above the Olterra. The outside party hammered and scraped the barnacles and other growth from the ship’s hull. The noise they created masked the noise of the workers inside the ship who were using an oxyacetylene torch to cut a four-foot square panel out of the hull. It also hid the sparks from the cutting operation. By the time the ballast tanks were emptied, and the ship restored to an even keel, there was a hatch, 2 metres below the waterline, through the hull into an interior water pool. Divers and maiales had a way to exit and enter the ship without being seen from above the water.

To the outside observer, including those at the British Consulate, the crew of the Olterra were carrying out systematic work routines, standing regular watches and accepting deliveries from ashore. Activity all designed to hide the real work being undertaken.

Visintini also insisted that the cook was an experienced chef; the Italians love their food and tasty meals were essential for keeping up morale. It turned out that the Spanish guards also liked a good Italian served with copious quantities of Italian wine. They guards were fed in a cabin in the aft part of the ship, well away from the ship’s renovations. Meanwhile, in La Spezia, the maiales were dismantled and the sections were packed into crates. The crates would be smuggled onto the ship disguised as spare parts and other pieces of nautical equipment. The breathing apparatus were packed into secret compartments in oil drums that were then topped up with diesel oil to fool any Spanish customs officer that may examine them.

Visintini officially ‘joined the ship’ on the 27th June1942 with civilian papers identifying him as Lino Valeri, the prospective first officer of the Olterra. He brought with him 3 technicians and a medical officer, Elvio Moscatelli.

On at least one occasion, Moscatelli acquired a donkey cart and filled it with fresh fruit and vegetables that he walked over the border from La Línea to Gibraltar. He set up his market stall in the dockyard and sold his produce whilst keeping an eye on the precautions then being taken against divers.

Back onboard the Olterra, astute observers were keeping a 24-hour watch from a porthole in the observation cabin, of all the comings and goings from Gibraltar harbour. They also noticed that, on the balcony of the British Consulate, mounted on a tripod, was a superb pair of binoculars. One dark night, an enterprising raiding party, quietly scaled the consulate wall, climbed to the balcony and made off with the binoculars. The observers gained a 64x view of the harbour.

In early July 1942, the twelve man team of assault swimmers from the 10th Light Flotilla, ‘Gamma’ group started to arrive on the Olterra. Six had been transported via Bordeaux from where they had crossed the Pyrenees on foot or hidden in the false bottom of a lorry. The other six went as legitimate crew of a cargo ship to Barcelona where they deserted. The skipper, unaware of their true identities or mission, reported their desertion to the Spanish authorities. All twelve frogmen were taken to a safe house in Madrid and from there to the Fulgor in Cádiz.

The frogmen arrived on the Olterra in ones and twos from the Fulgor, disguised as seamen and workers. They spent an inordinate amount of time lounging around on the upper deck, just as would be expected from a bunch of Italian merchant seamen. In reality, they were studying the harbour at Gibraltar and logging the water born patrol schedules, the procedure for entering and leaving harbour, the timing and extent of the preventative depth charging that was designed to ward off attacks from underwater and the sentry routine.

On the 13th July 1942, with the Olterra not quite ready to start operations, the frogmen were moved to the Villa Carmella where they could continue their observations of the commercial harbour at Gibraltar.

That night, all twelve frogmen left the villa, dressed in their black Belloni shallow diving suits and carrying their breathing gear, masks and fins. They crossed the garden and made their way down the dry arroyo Cachon that empties into the north end of Gibraltar Bay at Puente Mayorga.

All the frogmen also carried three mines each. Unlike conventional limpet mines that attach themselves to a ship’s hull utilising a strong magnet, these mines, known as cimici or ‘bugs’, sat in the middle of an inflatable ring, rather like a child’s swimming ring. The mine had to be positioned directly beneath the keel of a ship or against a flat bottom. The ring was inflated using a small, compressed air cylinder and the whole apparatus was only held in place because the ring was trying to rise through the water and was being prevented from doing so by the hull or keel above.

The frogmen gently swam towards the harbour at Gibraltar, ducking beneath the surface whenever a patrolling boat came close. One diver had his foot sliced by the propeller of one passing patrol boat whilst another suffered a concussion from one of the small depth charges lobbed into the water from the boats.

The remaining frogmen made it to the anchorage and placed their cimicis beneath several ships. All made it back to the Spanish shore where seven were arrested by carabineros and taken to Campamento. The Italian consul, Bordigioni, intervened and had them placed under loose arrest in a hotel in Seville. The remaining five were smuggled to the Fulgor in Cádiz and later repatriated to Italy.

Early in the morning of the 14th July, some of the mines exploded damaging four British cargo ships, the Shuna, the Empire Snipe, the Baron Douglas and the Baron Kinnaird. At least one of the mines floated to the surface and a few failed entirely.

Visentini was not satisfied with the performance of the mines used in the attack and he, together with Pistoni and Olterra’s captain, Amoretti, tested some of the mines just off the N340 main road between Málaga and Algeciras. They found that one mine took 15 minutes longer than the time set to explode and the other, 30 minutes longer. The mines used in the attack and for future attacks were stored at Pistoni’s house in Pelayo. From there they were sent to the captain’s house and were then taken aboard two or three at a time by the cook.

The Scire

On the 10th August, 1942, the Decima Flottiglia MAS team received some distressing news. The submarine Scirè that had done such sterling work in the early part of the Italian underwater operations at Gibraltar, was sunk by HMS Islay while attempting to attack the port of Haifa in British Palestine. She had 11 frogmen on board.

In September 1942, Decima Flottiglia MAS tried again. Two new frogmen from La Spezia signed on as crew aboard a cargo vessel bound for Barcelona. There they deserted the ship and made their way to the Olterra. Three crewmen from the Fulgor went to Seville and traded places with three of the frogmen detained there. The Spanish guards apparently counted heads rather than take note of faces or names. All five frogmen were taken to the Villa Carmella.

On the 15th September 1942, three of the frogmen entered the waters near Puente Mayorga. This time their task was more difficult. Now aware of the danger, though not the source, cargo and naval ships were being moored as far from La Línea as possible and as many as could be, were moored in the harbour. Patrols were more frequent, and searchlights were used extensively. Nevertheless, the frogmen managed to place cimicis beneath the 1787 ton steamer, Ravenspoint lying in the Commercial Harbour, 7 cables (about 1400 metres) from the North Mole. Three mines exploded and the ship sank.

By now thoroughly worried, the allies on Gibraltar were determined to stop the underwater sabotage attacks, especially as the numbers of capital and cargo ships was building up prior to the Operation Torch landings that would take place in early November.

In November 1942, Lieutenant Lionel Crabb, a Royal Navy mine and disposal officer, arrived in Gibraltar. Lieutenant Lionel Crabb and Lieutenant Licio Visintini became adversaries. The two had never met, and never would in life, but each was aware of the other and each came to deeply respect his opponent. Their rank was the only common factor between the two.

Crabb was red haired, short and stocky, whereas Visintini was dark, tall and slim. Crabb’s training regime involved copious quantities of alcohol, many packets of cigarettes and as little physical exercise as possible. Visintini exercised regularly and kept himself in shape. Crabb, despite his job, was a poor swimmer whereas Visintini of course was more than competent in the water. Crabb, again despite his job, had little time for the scientific and technical detail involved in mines, their discovery, dismantling and eventual disposal whereas Visintini, as we have seen, was very concerned about such details, although his aim was to have the devices explode. Visintini was a meticulous planner, leaving as little to chance as possible, Crabb had a ‘bull in a china shop’ approach, made ‘high jinks’ an art form and liked nothing more than blowing something up and making a big bang. He must have been a nightmare for any commanding officer. What both had in common, in abundance, was a huge dose of bravery and both were eminently suitable for their respective tasks. I suspect that, if these two polar opposites had ever met, they would have become great friends.

The underwater war at Gibraltar had just become personal.

When Crabb arrived on Gibraltar, two men, Lieutenant William Bailey and Leading Seaman Bell, were the entire underwater team, tasked with examining the bottom of every ship that sailed into Gibraltar. Crabb’s job was the safe disposal of anything they found. Crabb immediately offered to help the overworked pair.

The divers had no specialised gear. Their diving suits were ordinary overalls, worn over a pair of swimming trunks. Their fins were a pair of tennis shoes with weights attached. Their breathing apparatus was the Davis Submerged Escape Apparatus, designed to assist submariners escape from a sunken submarine. The DSEA were actually similar to the rebreathing sets used by the Italians. Unfortunately, neither Bailey nor Bell knew how to maintain the breathing sets, a procedure that involved changing the soda lime crystals in the rubber bag and replacing the oxygen bottles, after all they were only designed to be used once. The intrepid pair had liberated sixteen of the DSEA sets from the submarine depot ship, HMS Maidstone.

Back in July 1942, after the twelve-man attack on shipping in Gibraltar harbour, Bailey and Bell had been the only diving team that could respond. Bailey had swum beneath the ships, found many of the cimici mines and punctured their rubber floatation rings with a knife so that the mines fell to the bottom of the harbour where they could explode without causing any damage. For this deed, Lieutenant Bailey was awarded the George Medal.

Crabb performed his first dive wearing the makeshift kit the first afternoon he was on Gibraltar, unsteadily working his way over the submerged hull of a merchant ship guided only by a bottom rope suspended from the hand rail.

Within days of arriving on Gibraltar, Lieutenant Bailey broke his ankle and Crabb found himself promoted to Diving Officer.

Meanwhile, the Italians had developed a new type of mine, the details of which were discovered by an allied agent in Huelva when one washed ashore. The new mine was shaped like a torpedo and was about one metre long and weighed about 12 kilogrammes. It was attached to the hull by three G clamps. Instead of a timing device, the torpedo mine had two small propellors. As the ship moved through the water, the flow of water caused the propellors to turn. After a certain number of turns, the mine exploded. The idea was that these mines could be attached to ships in harbour and only explode after the ship was well out to sea. Blowing ships up in a neutral harbour and possibly injuring or killing neutral civilians would have certainly caused a political furore, something the Germans and Italians wanted to avoid, aware that they needed to keep Franco on side.

In early December 1942, an Italian diving team in the neutral harbour of Seville attached one such mine beneath the hull of a 1200 ton steamer called the Willowdale. The Willowdale arrived in Gibraltar on the 4th December carrying tungsten.

By now every ship entering Gibraltar had to undergo a bottom search. Crabb found the mine clamped to the hull beneath the engine room. Very little was known about this new type of mine. Were the clamps booby trapped to cause the mine to explode if they were tampered with? Was the clamp screw left-handed or right-handed? Was there a hydrostatic fuse that would explode the mine if it was moved into shallower or deeper water? At what speed could the mine be moved through the water without turning the propellors that ignited the fuse?

It took Crabb forty-five minutes and three breathing sets to detach the mine from the ship. He then suspended it beneath a buoy to keep it at the same depth and had it towed by rowing boat, slowly, to Rosia Bay. The following day, Crabb rowed the boat to the north end of the airstrip where he picked the mine up in his arms and carried it to a ditch. There he and his commanding officer, Commander Hancock, set about dismantling the mine. They found three separate back up timers attached to detonators, any one of which could have set the mine off.

Crabb was awarded the George Medal and promoted to Lieutenant Commander.

Crabb was not the only person on Gibraltar that liked a ‘good bang’. Helping to defend the two entrances into the harbour, between the moles, were a pair of Modified Northover Projector’s. This rather grand name disguised the fact that the projectors were not only homemade, they were also dangerous to their operators. However, they did make a satisfactory bang. Hence, they were a favourite weapon for the squaddies that operated them.

Each projector consisted of a five foot length of metal boiler pipe held almost vertical in a wooden frame. Welded to the bottom end of the pipe was the butt, trigger and bolt action loading mechanism from a Lee Enfield 303 rifle. The ammunition was ordinary food tins, 4.5 inches x 3 inches; think of a baked bean can, filled with 1.5 lbs of TNT with a nitrocellulose fuse that would burn underwater. The end of the fuse projected from the bottom of the can.

Operating the projector consisted of loading a blank cartridge into the breech mechanism and sliding a prepared can down the pipe, fuse first. When the trigger was pulled, the cartridge fired, igniting the fuse that was then propelled out of the pipe with the can. The can landed in the water some distance away and sank beneath the surface. It exploded when the fuse burnt down to the TNT. That was the theory. A number of things could go wrong. The fuse could fail to ignite, that was quite common, so the can ditched in the water with no resulting bang. The fuse could ignite but the can became stuck on its way up the pipe. That was also fairly common, the resulting bang was satisfactory but tended to destroy the apparatus and anybody near it. For that reason, a long length of string was attached to the trigger and the operators sat behind a concrete wall when the thing was fired.

By December 1942 the Olterra, her torpedoes and crews, were ready for their first attack which turned out more ambitious than they could have dreamt of. On the 6th December, after taking part in Operation Torch, the landings in French Morocco and Algeria, Force ‘H’ including the battleship HMS Nelson, battlecruiser HMS Renown, aircraft carriers HMS Furious and HMS Formidable together with support ships entered Gibraltar.

Lieutenant Licio Visintini had been studying the mortars fired on the moles through the British binoculars stolen from the British Consulate balcony. He saw that the shots were irregularly fired at roughly three-minute intervals.

On the night of the 8th December 1942, Visintini and his men set off on three maiales from Olterra. Their targets were the Nelson, Formidable, Furious and Renown.

The maiale, driven by Lieutenant Visintini and Petty Officer Magro, was hit by one of the homemade charges from one of the Modified Northover Projectors. The bodies of Visitini and Magro were recovered later by the British still in their frogman suits. Crabb visited the corpses in the mortuary and arranged for a Catholic priest to officiate at a burial at sea for the two men. Crabb dropped a wreath in the water. Such was the respect Crabb had for Visitini that he stayed in touch with Visitini’s wife, Maria, and later, in 1945, whilst clearing mines from the canals in Venice, took her on as a secretary.

The second maiale, manned by a Second Lieutenant Cella and Sergeant Leone, was spotted on the surface by a searchlight but managed to slip beneath the water and avoided the submarine chasers that were by now searching the anchorage furiously. Leone was washed from the torpedo and his body was never found but Cella managed to return to the vicinity of the Olterra where he scuttled his craft and returned to his base. The maiale was later brought back into the Olterra and repaired.

The third torpedo, manned by Midshipman Manisco and Petty Officer Varini, was also caught in searchlights and chased. Running out of air they scuttled their craft and took refuge on an American freighter and later gave themselves up to allied troops on Gibraltar. When interrogated they maintained the attack had been launched from the submarine Ambra.

Undeterred the Italians re-supplied the Olterra with men and torpedoes. A Lieutenant Notari took charge of the Olterra group.

Crabb found his team expanded to six divers and the Gibraltar Underwater Working Party, as it was now known, moved into Jumper’s Bastion where they billeted with the army bomb disposal team. The team were busy. Every ship, up to fifteen per day, had to be checked for mines. Gossip and innuendo from allied agents was also starting to point a finger at the Olterra as being the source of the maiales and crew.

Two of the British divers, Morgan and Knowles, disguised themselves as crew and took the Spanish waterboat to Algeciras where they strolled over to the Olterra mooring. What they saw reinforced the chatter. Crabb was all for mining the Olterra at its mooring but this action, indeed any further physical attempts to confirm the Olterra was a frogman base, were vetoed by the British Cabinet no less. The reason given was valid, that Britain did not want a diplomatic incident that could cause Franco to enter the war on the Axis side. This author also strongly believes that the radio codes used by the Italians in communication with their agents and officials in Spain had been cracked and Churchill was determined to keep that secret for as long as possible.

On the 8th May 1943, a dark and stormy night as it transpired, three maiales set off from the Olterra. Their targets were allied freighters anchored as far as possible away from Algeciras. Second Lieutenant Cella, the only one to make it back from the first attack, was in charge of one of the maiale. This time the teams were more fortunate. They successfully mined three freighters, an American liberty ship, Pat Harrison that was severely damaged and became a total loss, the British freighter Mahsud which sank to the bottom with its upper works still visible and the freighter Camerata which sank outright. All three maiales and their crews returned safely to the Olterra. A stunning success. To mislead the allies into thinking the attack had been made by combat swimmers an Italian team scattered scuba gear along the Spanish shore.

The team from the Olterra continued to plan and execute attacks against allied shipping. In June 1943 the entire Ursa Major team was awarded the Medaglia d’oro for their deeds, but the war was not going well for the Axis powers.

On the 13th May 1943, the Axis powers in North Africa had surrendered. The allies had invaded Sicily on the 19th July and were preparing to attack the Italian mainland.

On the 25th July 1943, Mussolini was removed from power, Italy was on the brink of collapse and negotiations towards a peace treaty between Italy and the Allies had already, tentatively, started.

Notari was determined to fight to the end.

On the night of 3rd August 1943, the Ursa Major team made their last foray. Notari led three maiales and successfully reached the anchorage undetected. He unattached his mine beneath a liberty ship, the Harrison Grey Otis. Whilst his crew member, Petty Officer Giannoli, was working to attach the mine the maiale malfunctioned and crash dived to a depth of 34 metres. It then careered to the surface with Notari half conscious. Having lost Giannoli, and with his craft damaged, Notari made his escape at full speed on the surface, his wake covered by a troop of dolphin that fortuitously accompanied him and disguised his wake. Giannoli meanwhile had attached the mine and climbed onto the ship’s rudder. After two hours he called for help and was taken aboard. A member of Buster Crabb’s team was called to search the hull for mines but the mine exploded before the diver entered the water.

The Otis was declared a constructive total loss. The other two crews had also done their work and the Norwegian cargo ship Thorshovdi and the British cargo ship Stanridge were sunk.

Just one month later, on the 3rd September 1943, the Armistice of Cassibile was signed between Italy and the Allies, ending Italy's part in the war.

Lieutenant Notari and his Ursa Major team finished their war on a high note and Operation Ursa Major was over.

Ellison, K. 'Special Counter Intelligence in WW2 Europe' (Revised 2021)

Kemp, P. 'Underwater Warriors' (1996)

O'Connor, David. 'Blowing up the Rock'

Rankin, 'Defending the Rock: How Gibraltar Defeated Hitler' (2017)

National Archives: 'The Bridges Enquiry into the disappearance of Commander Crabb' CAB 3-1/121, 122, 123, 124 and 125