The WWII Evacuation of Gibraltar. Following the outbreak of the Second World War in September 1939, the British Government decided that the bulk of the civilian population should be removed from Gibraltar as soon as possible. This is the story of one of those evacuees, a 5-year-old girl called Lydia Viagas.

By Nick Nutter | Updated 15 Mar 2022 | Gibraltar | History |

Login to add to YOUR Favourites or Read Later

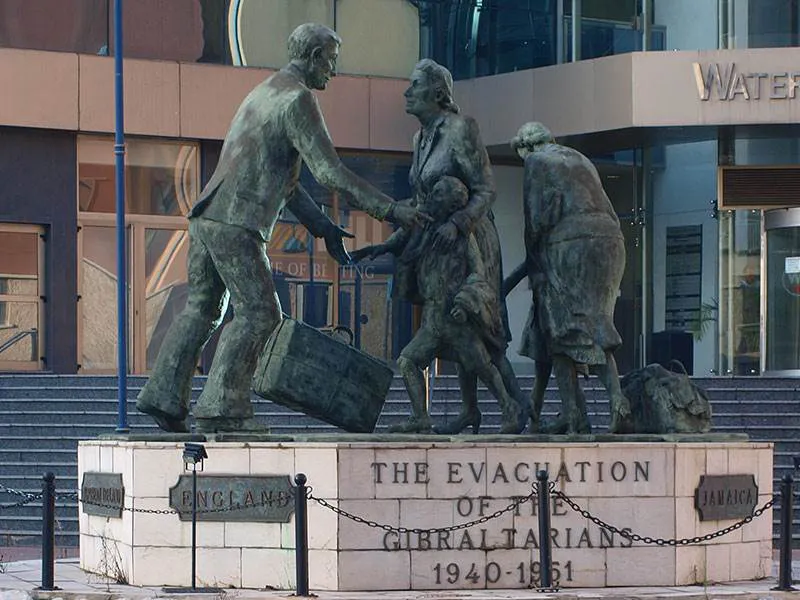

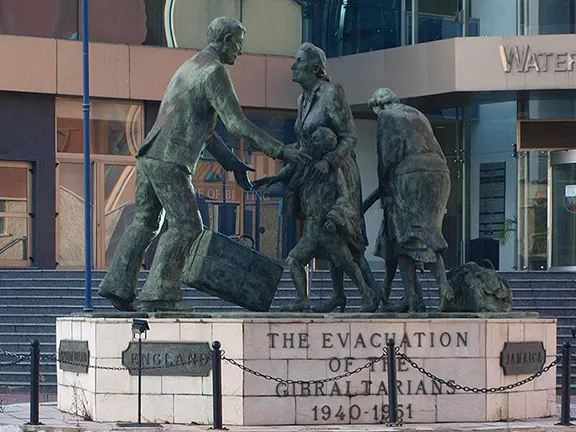

The Evacuation Memorial Gibraltar

Following the outbreak of the Second World War in September 1939, the British Government decided that the bulk of the civilian population should be removed from Gibraltar as soon as possible. Only two thousand civilians, those considered to hold jobs essential to the war effort, were allowed to remain. Many of the evacuees would never see their homes again, and some of those fortunate enough to survive the war would have to wait ten years or more before being reunited with family left behind and those who had been evacuated to different places.

This is the story of one of those evacuees, a 5-year-old girl called Lydia Viagas. She remembers her family living in a small house in the Old Town. The address shown on the embarkation records is 4, Danino’s Ramp. Her father, José, worked at what was the Lipton’s Grocery Store on Main Street which then became Princess Silks opposite Marks and Spencer. He also played football for the Gibraltar football club. She was evacuated with her mother, Imperia Viagas (nee Psalia), who was then 32 years of age.

Between the 21st May and the 24th June 1940 about 13,500 evacuees, the majority being the elderly and women and children were shipped to Casablanca in French Morocco. One ship, the Egyptian owned Mohamed Ali el-Kebir, operated a shuttle service between Gibraltar and Casablanca making twelve journeys in all and transporting 12,044 evacuees. On one of those trips, the passengers included Lydia and Imperia Viagas, along with Imperia’s two sisters, Leonor Segui (née Psaila – aged 36), and Josefa Golt (née Psaila - aged 35), and their invalided mother, Marianna Psaila Orfilla aged 69. Leanor had a one-year-old daughter, Marilou. Leonor, Josefa and Marianna all lived at 8, Lime Kiln Steps. Lydia’s father, José, remained behind in Gibraltar. He was later to join the merchant navy. On his last voyage on a Russian convoy, his ship was torpedoed and sank in the frigid Arctic waters. He was one of the few lucky ones to be rescued, and he was able to reunite with his family who was by that time, in London.

Lydia

The evacuees were communally housed in six dance halls and at a camp in Ain Chok, a town near Casablanca. Conditions were not good with buckets for communal toilets, mattresses and straw for bedding and inadequate food. The fortunate ones had friends in the towns of Safi, Mazagan or Oued Zem who could house them. The evacuees in the dance halls were classified into three groups, those that could afford decent accommodation, those that could only afford basic housing and those, the majority, that needed financial help. The French wanted the British Government to provide financial assistance and pay for the building of five hundred huts that would house 3,000 Gibraltarians in the industrial area of Roche Noires.

Two days before the last evacuees arrived in Casablanca, on the 22nd June 1940, the French capitulated to the Germans. The new Vichy French Government, sympathetic to the Germans, found the Gibraltarian civilians an embarrassment and looked for opportunities to remove them.

Relationships between the French Protectorate in Casablanca, and the British, and consequently the Gibraltarian evacuees became even more strained after the 3rd July 1940 following the British fleet’s attack on the French fleet at Mers-el-Kebir. Over a thousand French sailors were killed in the attack, and some French warships were destroyed to prevent them falling into the hands of the German Navy. Feelings ran high in Casablanca, home to a French naval base. The sailors and their families stationed at Casablanca had known men on the ships attacked, making the assault a personal insult as well as an affront to France.

On July 6th the French Protectorate insisted that all Gibraltarian evacuees leave Casablanca immediately or “measures would have to be taken for their protection”.

The Gibraltarians were not particularly welcome in Britain either. John Anderson, the minister for home security, told the War Cabinet, it was “desirable to prevent the refugees from being landed in this country if possible, as we have no means of dealing with them except in internment camps”.

The Foreign Office appealed to Britain’s allies and colonies. Portugal agreed to allow 2,500 evacuees to live on Madeira provided there were no Republican Spanish amongst them. South Africa granted shelter to a small number who were “British subjects of English race” but not “Spanish people of Spanish extraction”. Mauritius took 5,000 on condition Britain funded the construction of living quarters. In the meantime, the evacuees would live in canvas tents. Jamaica said it could put 2,000 people in hotels but building a camp to house them would take two months. The island’s Governor, Sir Arthur Frederick Richards, pointed out to London that, “the number proposed is larger than any town in Jamaica except Kingston”.

On the 10th July, an astonishing sight greeted a Commodore Kenelm Creighton who sailed into Casablanca with 15 British merchant ships carrying 18,000 French servicemen who had been rescued from the beaches at Dunkirk. Waiting on the quay was a horde of Gibraltarians clutching bags and suitcases and being guarded by troops. Lydia and her relatives were amongst the mass. As the repatriated soldiers left the port, the civilians were herded towards Creighton’s ships. His ships were immediately interned until Creighton agreed to allow the Gibraltarians aboard. The French authorities refused permission for Creighton to clean or restock his ships. While Creighton pleaded the evacuee's case, they stood in the baking sun with more arriving every hour. Despite having orders from the Admiralty not to take on civilian evacuees and despite him not being allowed by the French to clean or restock his ships Creighton opened his gangways. He now had a huge problem. His vessels were not equipped to deal with 1,000 passengers each, they had no kitchen that could produce that sort of quantity of food, and the French had refused to allow him to wait for field kitchens to arrive. The design of the ships themselves, vertical ladders between decks and small hatches, was not suitable for the elderly or children.

Teresa Maria Knight

Creighton decided that his only choice was to sail for Gibraltar, 220 miles away and only 11 hours sailing time at 20 knots, with his passengers occupying the upper decks. When he announced his decision to the Admiralty, his commanding officer, Admiral Dudley North replied, “For heaven’s sake don’t. We had enough trouble getting them out”.

The last of Creighton’s convoy arrived at Gibraltar on the 13th of July. Initially, the Governor, Sir Clive Liddell, refused to allow the evacuees to land. He feared, quite rightly, that once ashore the Gibraltarians would scatter and refuse to leave again. It was only after a public protest in John Mackintosh Square and a petition taken to him by Acting President of the Exchange and Commercial Library and two councillors that Liddell reluctantly allowed the evacuees to leave the ships while they were cleaned and provisioned. Lydia and her mother were briefly reunited with José.

On the 18th of July Gibraltar experienced its first air raid. In retaliation for the attack on the French Fleet, the Vichy Government authorised an air strike against Gibraltar.

In the meantime, Creighton’s ships were cleaned and re-provisioned for the 16-day journey to Britain. The embarkation records show that, on the 26th of July, Marianna, Leonor, Marilou (recorded as Maria de la Luz in the embarkation record), and Leonor’s seven-day-old twins Violetta and Alfred, embarked on the S.S. Athlone Castle. The record reveals a small mystery. A family story tells of the twins being born while the ship on which they were passengers was evading U boats. Their birth certificates show them as having been born at sea on the 29th of July, three days after embarkation. The embarkation record for the Athlone Castle also recorded incorrect ages for Marianna and Leonor. There were many inaccuracies on the embarkation records as the authorities hurriedly dealt with thousands of residents as those in power rushed to have them once more removed from Gibraltar.

On the 29th of July, Lydia (recorded as Lidia in the embarkation record), and Imperia (recorded as Hemperia in the embarkation records), were put on board the S.S. Strategist.

The convoy of 12 ships sailed on the 30th July. Josepha was to remain behind until the 19th August when she sailed to the UK on the S.S. Neuralia.

Creighton’s route took him far into the Atlantic Ocean to avoid German U Boats. With his cargo of now only 12,000 evacuees successfully rounded up on Gibraltar, he set out with just one escort ship, a Corvette, HMS Wellington. Lydia remembers they had to sleep on mattresses they had brought with them, bedding being in short supply.

Within six days most of the provisions were inedible due to poor storage conditions. Water was strictly rationed. Evacuees delivered babies born during the voyage. Some elderly evacuees died during the journey and were buried at sea. Without the loss of any ship, however, Creighton shepherded his flock into Liverpool, Swansea, Cardiff, and Bristol. Lydia and Imperia found themselves in Swansea where they disembarked on the 14th August.

From their port of disembarkation, the evacuees were taken by train to London. They arrived just in time for the Blitz that started on the 7th September. The evacuees found themselves housed in groups in places such Dr Barnardo’s Home and Whitelands College while a lucky few were accommodated in housing left by Londoners evacuating London in the Wembley and Kensington areas. After a brief time at Wembley where Imperia gave birth to Flodelis, Lydia and her mother found themselves living in Kensington Palace Mansions whilst her grandmother and aunts stayed at the Empire Pool at Wembley Stadium. Both Leonor’s twins died of gastroenteritis at the age of 5 months while at Wembley. The Empire Pool was used as a permanent hostel for Gibraltarian evacuees throughout the war. Its enormous windows were blacked out for the duration.

Concern for the safety of the evacuees during the Blitz led to 2,000 being shipped to Madeira. Jamaica received about 2,000 evacuees who travelled there directly from Gibraltar during October 1940.

Meanwhile, Lydia, Flodelis and her mother moved to Tottenham. They were housed in a school. Lydia remembers that they each had a room and that they were fed communally in the canteen. Because they were being provided for, the evacuees were not issued ration books. Lydia’s mother used to buy bacon bones and make soup. Sometime during this period Lydia’ father, José, managed to re-join his family in London. He became an Air Raid Warden. One night, while on duty, he saw a bomb land on the local hospital. He rushed there as fast as he could, his daughter had been recently admitted with tonsillitis. When he arrived, he was refused entry until the building was safe. It was a few hours before a relieved José was told that Lydia was not one of the dead or wounded. He later told her that he had run so fast that his legs would not support him when he got to the hospital. Lydia was much more fortunate than five year old David, another patient and the son of one of her mother’s friends. He was killed in the blast and could only be identified, beneath the bandages that entirely covered his head, by his teeth, the only part of him still intact.

Danino's Ramp - Returning Home

Following the surrender of Italy in September 1943 Gibraltar became less important as a strategic position, and the military presence was scaled down releasing the housing they had occupied. It was decided to start repatriating the Gibraltarians. The first group of 1,367 repatriates arrived in Gibraltar from the UK on the 6th April 1944. The first repatriation party left Madeira on the 28th of May, and by the end of 1944, there were only 520 evacuees still on the island.

Repatriation, however, depended on there being accommodation available on Gibraltar, school places for children, medical services able to cope with an increasing population and, initially at least, family members already on Gibraltar to support those returning. José, Imperia and Lydia did not meet the conditions for early repatriation.

In London, once the risk of air raids decreased, people wanted to return to their homes. Homes that were now occupied by Gibraltarians. As a result, 500 Gibraltarians were re-evacuated to Scotland and 3,000 to camps in Northern Ireland. The evacuees were told that they were en-route to Gibraltar with a brief stop in Ireland. Consequently, many sent most of their possessions, including winter clothes, by courier, back to Gibraltar.

So it was that, in 1945, Lydia, together with her sister, mother and father, found themselves in a camp in Northern Ireland. This period was probably the unhappiest time for the family. There was no work to be had, and in any case, no-one in the family had the necessary ‘Permit’. Conditions in the camp were primitive. Only one camp had electricity. The evacuees were still not entitled to ration cards. Imperia was given a weekly allowance of 2 shillings and 6 pence plus an extra 6d per child. Altogether there were twelve camps in Northern Ireland, eight of which were in County Antrim.

Since nobody expected the camps to be occupied for long, they were made up of Nissen huts in fields. There were large huts for the school, community centre and kitchen and smaller huts for families. Each of the family huts was divided into two, one part for the men to sleep in, the other for the women. Lydia remembers that everybody spoke Spanish in the community centre. During the winter the men would make coats from army blankets since many evacuees were dressed in clothing more suited to the Mediterranean.

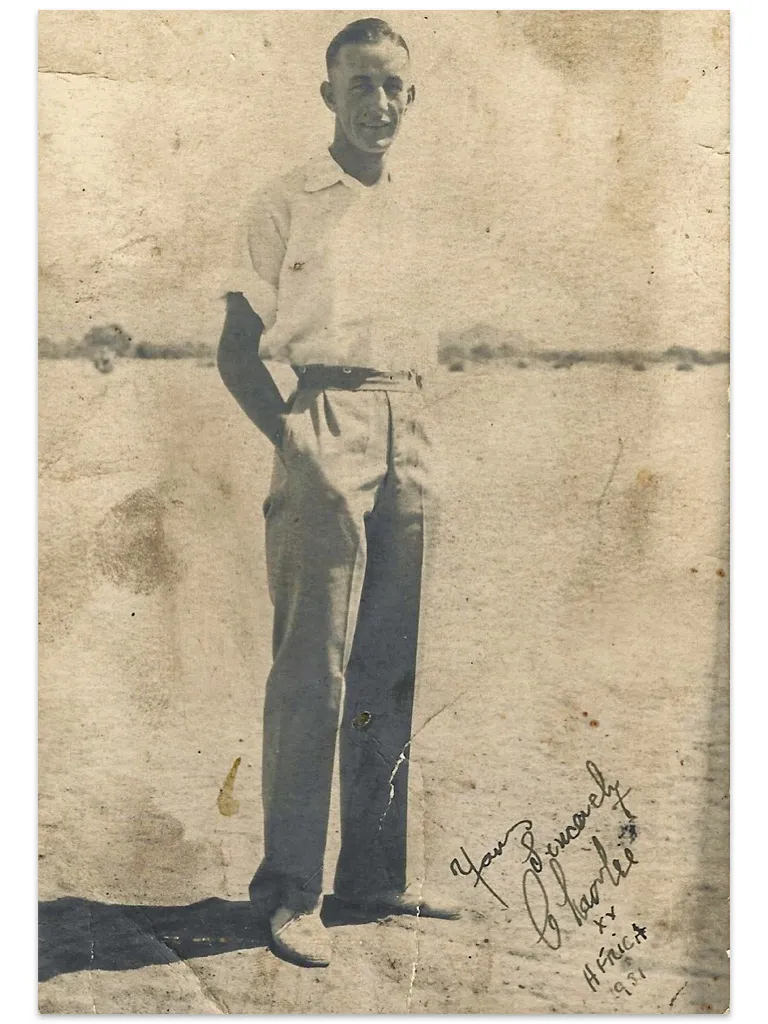

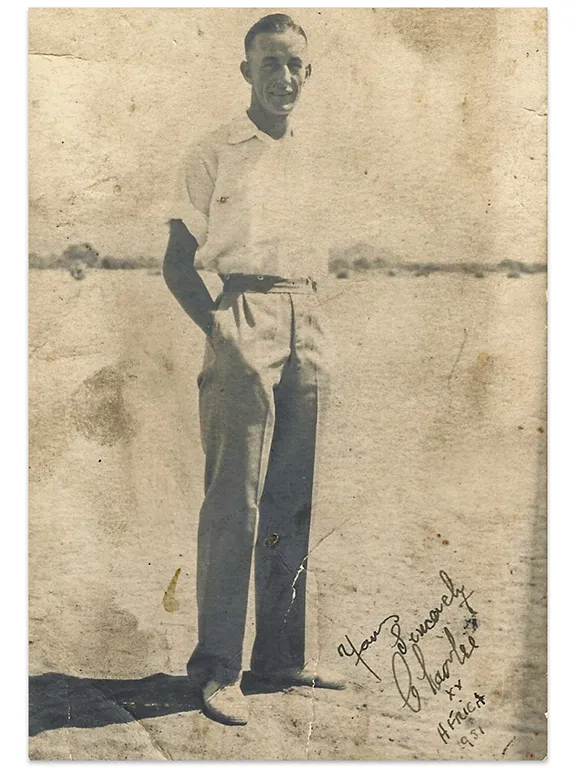

José at this stage called upon the services of, Teresa Maria Knight (nee Plummer), his half sister whose husband, William Charles Knight, a Welshman, lived in Swansea. José found a job in Swansea and was able to remove himself from the evacuation programme. He was soon able to return to Northern Ireland to retrieve his wife and daughters and from there move to the Victoria area in London. With a decent job, José was able to relocate to a large flat in Camberwell and rescue his extended family from the Irish camps.

Leonor, her daughter Marilou, Josefa, and Marianna went to live with José, Imperia, Flodelis and Lydia. The children were placed in local schools, and the family settled into their new home. By the time José was eligible for repatriation, it would have meant, once again, uprooting an entire family from a place they now called home.

William Charles Knight (Africa 1931)

On the 27th December 1945, the case of the Gibraltarians was brought up in Parliament by Sir Hugh O’Neil, MP for Antrim. His whole question and the answers as recorded in Hansard provides an insight into the hardships being suffered by the evacuees and the inequities forced upon them.

Sir Hugh pointed out that while in London many Gibraltarians had found work and between them contributed £70,000 to unemployment insurance. Those without jobs in Northern Ireland found they could not claim unemployment benefit because they had not resided in Ulster long enough to qualify for a residence certificate.

He went on to mention the lack of drainage, causing muddy ground, inadequate clothing and the general dissatisfaction of the residents who had not expected to be there beyond a few days.

In a concluding statement, Miss Horsbrugh (the Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Health) said, ‘On the whole, we have made the camps as good as we could, but these people are away from home and they want to go back. We want them to go back, too, and we will do everything we can to get them back as soon as possible.’ As late as 1947 there were still 2,000 Gibraltarians in camps in Northern Ireland, and the last of the evacuees would not see the Rock of Gibraltar again until 1951.

In Funchal on Madeira, alongside a small chapel at Santa Caterina park is a memorial that was made in Gibraltar and shipped to Madeira to express the gratitude of the people of Gibraltar to the island of Madeira and its inhabitants. On Gibraltar, the evacuees are remembered with a statue on the roundabout on North Mole Road and a plaque in the lobby of Gibraltar’s Parliament.

Lydia would not return to live in Gibraltar until 2011.

Footnotes:

1. On the 7th August 1940, the SS Mohamed Ali el-Kebir, whilst carrying munitions from Avonmouth to Gibraltar, was torpedoed and sunk by U Boat 38 commanded by Captain Lieutenant Liebe.

2. The Athlone Castle survived the war and continued in service until 1965.

3. The Strategist retired from service in 1946.

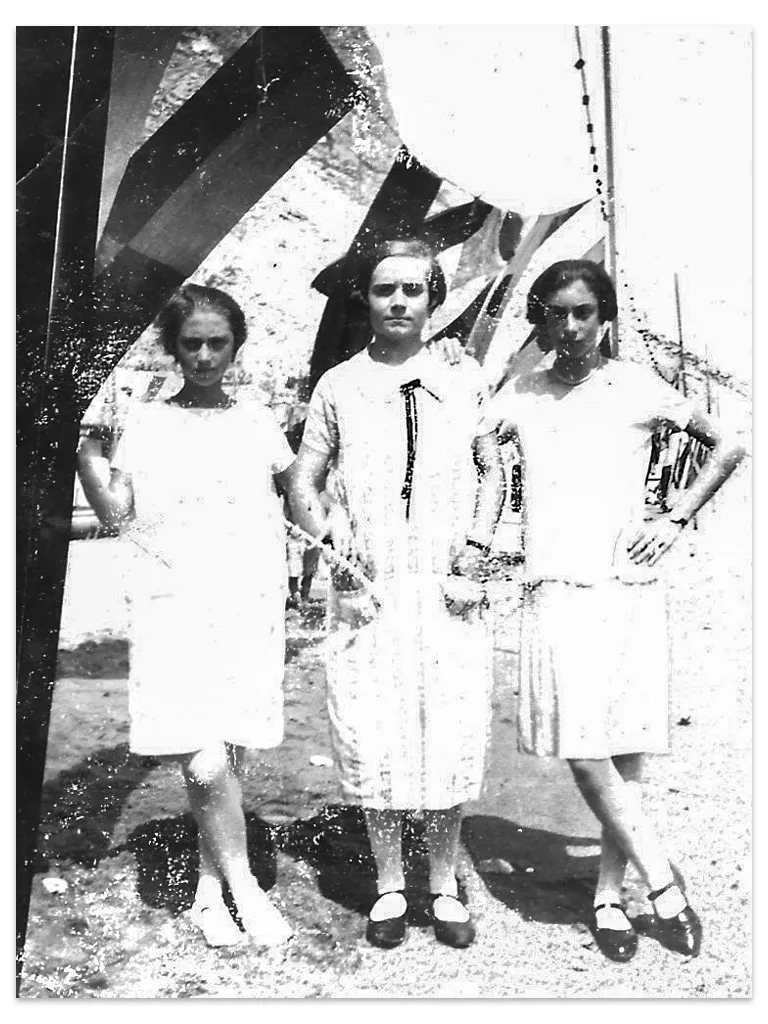

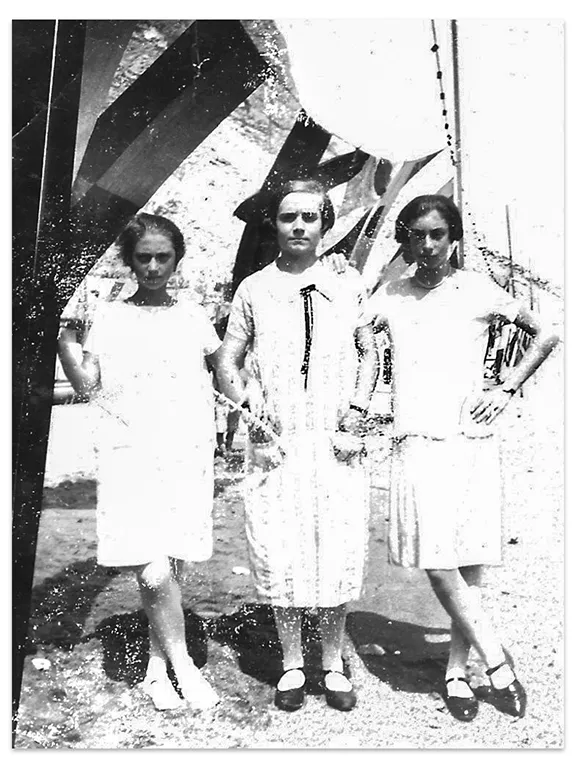

Antonia Garcia, Imperia and Teresa (Gibraltar 1926)

Sir Hugh O'Neill (Antrim)

I want to call attention for a few moments to the evacuees from Gibraltar who were sent from London to Northern Ireland last summer. I have seen a good deal of them there since they arrived. They are, as my right hon. Friend knows, because she has seen them there, quartered in camps in Nissen huts. They are very close quarters, there is no electric light, the sanitation in the camps is very primitive, and, when the wet weather of the winter started, the mud was very bad indeed, but that has certainly been improved a little by the construction of concrete paths in the camp, and it is certainly very much better than it was. Generally, the condition in the camps has certainly very greatly improved in recent months. As my right hon. Friend stated in an answer to a Question in this House when she returned from visiting these camps, the food there is good and the children are getting education, the small ones in schools which have been built in the camps, and the older ones in the secondary schools in different towns. Surprising as it may seem in a Northern and rather damp climate, such as that of the North of Ireland, the Gibraltar evacuees, on the whole, have enjoyed very good health, particularly, I believe, the children. But, in considering the situation of these people, one must remember that they are not internees. They are British subjects, inhabiting one of the key points of the Empire. They had to leave Gibraltar not because of enemy action, but because their homes were wanted for purposes connected with the defence of Gibraltar. One cannot help feeling great sympathy with them in their exile and their plight.

There are one or two specific points which I would like to raise and I hope my right hon. Friend will be able to give me an answer. First, with regard to unemployment insurance. I understand that, while the Gibraltarians were in London, they contributed over £70,000 in unemployment insurance contributions. Most of them are now out of work and they cannot draw any benefit, because, under the law in Ulster, a residence qualification is necessary before benefit can be drawn and they have not been there long enough to qualify. I know that this is giving very great dissatisfaction to many of them, and surely it is a matter which could be quite easily put right by arrangements between the Government of Northern Ireland and that of the United Kingdom. I should be glad if my right hon. Friend could tell me something about that.

With regard to work and employment for these people, in London, most of them were employed and were earning good wages. In Ulster, except for one camp near Belfast, where I think they are nearly all employed, the great bulk of the people are out of work. Most of the camps are in purely country districts and there is really no work available other than agricultural work.

Some got temporary employment during the harvest—I had some myself. They are not naturally agricultural workers and, anyhow, in the case of the few who got work in the harvest, it only lasted a comparatively short time. There is another point as regards work for them. I am told that many of the people for whom they worked when they were in London are willing to have them back, and would like to employ them now. If that is so, are they allowed to come to London to take work, and if not why should they not be allowed?

As hon. Members probably know, there is a travel permit system operating between Great Britain and the North or Ireland, which restricts travel by anybody; and, of course, the Gibraltar evacuees are subject to that, like everybody else. But it seems to me that it is a definite restriction of their liberty, through no fault of their own, by the chance, the hazard, that they happen to have been evacuated there, rather than to some other part of the United Kingdom. I am also told that the Ministry of Health exercise a veto on Gibraltar evacuees coming to this country, even in cases in which, under the law, their travelling has been approved. I do, not know if that is so, but if it is, I know that it causes a good deal of resentment, and I do not think that the Ministry should intervene and prevent people from coming to London or to Great Britain if their permits have been approved.

Another point I would like to raise is with regard to these people's clothes. When they were sent to Ulster they were told, indeed I was told, that they were really going there en route to Gibraltar, and that they would be sent home direct by ship within a reasonable time. Owing to that, I understand that several of them sent direct to Gibraltar luggage, in which was packed a certain amount of their clothes, and that when they got to Ulster they really had not sufficient clothes for the winter. Certainly, those whom I have teen appear to be very lightly clad for a cold Northern winter. Most of the women seem to have light cotton frocks and the men very light suits. Further, the conditions in which they are living in these camps inevitably mean that there are great wear and tear on their shoes and boots, which wear out much more quickly than they would, for instance, on the pavements of London. I do not know whether any arrangement has been made, or could be made, under which they can obtain extra coupons to enable them to get the extra shoes and clothes which, I am quite convinced, they ought to have.

Another point, which really concerns the Colonial Office more than my right hon. Friend, is that the forthcoming elections under the new Gibraltar Constitution are to be held, I believe, some time in the spring or early summer, and I have been asked by some of the leading Gibraltarians to find out from the Government whether they will be allowed to vote at the General Election in Gibraltar under such a system as applies to our Servicemen at our General Election, and also whether any of them who may wish to stand as candidates for the election at Gibraltar will be allowed to travel to Gibraltar in order to do so. I asked a Question of the Colonial Secretary a few weeks ago, but it was not reached in time for an oral reply, and the written reply simply said that it was not possible to provide any facilities for enabling them to vote in this country on the occasion of the election in Gibraltar. The number of these evacuees runs into several thousands and it seems rather hard on them—many of them are responsible people in Gibraltar—if they are not allowed to vote at their election or to stand as candidates. I cannot really believe that it is not possible to devise some method by which they could vote as absentees.

Over and above all these matters the main point which is worrying these people more than anything is, What chance is there for them to be allowed to go back to Gibraltar? That is what they want above all else. They want to go home. They have been away from their homes now for more than four years, and naturally they want to go back as soon as possible. I am very glad that the Government have recently taken some steps at any rate with regard to that by appointing Sir Findlater Stewart as, a kind of commissioner to examine the whole question of the possibility of repatriation. I am sure that they could not have made a better appointment. I know him well, and I am sure he will do the job as well as anybody could do it. He was in the North of Ireland last week going over camps, and I believe he is going out to Gibraltar very soon to investigate that end of the problem, and I hope that, as a result of these investigations, it will be found possible to speed up the repatriation of Gibraltarians.

One has to remember that since these people left Gibraltar many children who were then boys and girls have now become young men and women. That these young people should be compelled to live a life of idleness without work or occupation is a most lamentable situation, but, in spite of this, their behaviour has been, on the whole, remarkably good. This aspect of the matter is causing very great concern to the parents and some of the older friends of the young people, who dread the effect which this period of idleness and lack of occupation may have upon them and what eventually may happen when they return home and have to stand on their feet once again. I know that the Government are sympathetic. What I ask is that they should translate their sympathy into action by doing their best to remedy any reasonable grievances, and, above all, by speeding up the repatriation of these Gibraltarians to the utmost possible extent.

The Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Health (Miss Horsbrugh)

I am glad that my right hon. Friend has raised this matter because it gives me an opportunity of putting some of the facts that it has not been possible to put by way of answers to questions. I want to say, in the first place, how fully I sympathise with people who are away from home, and who want to get home, and I can assure my right hon. Friend that not only do we sympathise, but we are very anxious that these people should return to their homes. As I think the right hon. Gentleman knows, during 1944, 9,400 went home, but I feel sympathy for the 5,800 who are left. It feels worse when you are away from home, and wanting to go home, to be in the minority who have to stay, while those who came away at the same time as you came away, have been able to return. It is, therefore, for this nucleus which is left that I feel much sympathy.

The difficulty is a matter of housing. Perhaps it may be asked, Why if these people came from Gibraltar, is there not room now for them to go home? The right hon. Gentleman referred to the number of boys and girls who have reached adolescence, and to the overcrowding there was in Gibraltar originally, but I think it is not always realised that about 2,500 of these people lived outside Gibraltar, in Spain. About 1,000 lived in what were called "War Department lettings," which are now being used for War Department work. About 2,000 lived in houses which have been demolished, either by enemy action or for military reasons, during the present war. About 100 lived in houses which are still under requisition, but I would like to make the point that the number of houses under requisition is very small and that it is the other difficulties which we really have to face. That is why it has been thought that at the present time no more than 14,000 ought to go back to Gibraltar; the number there now is over 13,600. I think it is best to state these facts because I want to make it clear that it is a problem of how housing accommodation is to be provided. I know that some of those who went back in the latter part of last year are still in transit camps. When some hon. Members have suggested that more camps might be built, I think those who have been to Gibraltar will realise the difficulty of finding sites on which to build camps, and it is even more difficult now than it was before the war, because a certain amount of land has now been taken up for airfields. So my first point is that we are anxious for these people to return, and the difficulty is simply and purely one of housing accommodation.

As the right hon. Gentleman said, Sir Findlater Stewart has been to Northern Ireland, and is going to Gibraltar to see what arrangements can possibly be made. Sites have been found for temporary housing schemes, but there is no use blinking the fact that my right hon. and gallant Friend the Secretary of State for the Colonies has a very serious problem in the housing arrangements in Gibraltar. Sir Findlater Stewart is to look into this to see what he can suggest, and the housing problem being such, I quite agree with my right hon. Friend that what we should do is to see how we can make the best possible conditions for the number who are still with us.

My right hon. Friend mentioned the election for the city council. The difficulty about arranging for votes for those outside Gibraltar is this. The electorate is not large; the number in Gibraltar who will be able to vote is calculated at about 4,600. I am informed that the number of those who would be eligible to vote who are now outside Gibraltar is about 1,600 at the most We know that we have still in this country about 1,000 who did not go to Northern Ireland. There is also the number in Northern Ireland, and there are some in Spain, some in Tangier, and some in Madeira. The matter has been looked into very carefully, but I am informed that no scheme could be found by means of which it would be possible to deal with this small and scattered number. It has, however, been arranged that the Council should be elected for a shorter period than usual, up to 31st December, 1947.

Sir H. O'Neill

Was the question of voting by proxy examined?

Miss Horsbrugh

Yes; the whole matter was gone into very carefully, but it is a difficult problem when there is a small number of people, who are widely scattered. There are some in Northern Ireland, some in England, some in Spain, some in Tangier, and some in Madeira. The matter was looked into to see what could be done, but the authorities came to the conclusion that it was practically impossible to make any arrangement for voting and they suggested making the term of office shorter.

Sir H. O'Neill

What about candidates?

Miss Horsbrugh

It has been decided that it is not possible to deal with candidates who are outside Gibraltar. The right hon. Gentleman pointed out some of the other difficulties, one of them being unemployment insurance. I would like to make this matter clear now, because I tried to make it clear to individual evacuees in Northern Ireland, and I am not sure that I was successful. By law, these people must reside in the country five years before they can draw unemployment benefit and, therefore, their status is exactly the same as that of other residents. They have not been singled out for different treatment, as compared to other people in Northern Ireland. I am sure hon. Members will agree that if evacuees were drawing unemployment benefit, it would only be natural that they should pay something towards their board and lodging. I do not think it would be right that this money should be given to evacuees simply as pocket money. The unemployment allowance for a man, his wife and two children is, at present, £2 10s. a week. The evacuees in Northern Ireland have no expenses for rent or food. Everybody will agree that the food is good, that there is plenty of it and that there are the orange juice, cod liver oil and so on for the babies, and, moreover, that medical attendance is free. A family of evacuees of the number I have described, is now receiving 13s. 6d. a week as pocket money. I believe their financial situation is as good as, or even better, than if the family were drawing unemployment benefit, and living on their own. I think we have made the financial arrangements as good as they would be under the unemployment insurance scheme or better and, further, their status is the same as the status of every citizen of Northern Ireland.

As to the problem of work, I quite agree that it has been very difficult, but I would remind the House that these people were anxious to get away from the flying bombs, and I do not wonder. Our own women and children were being evacuated. We knew the Gibraltarian families did not want to be separated. At the time of the earlier bombing one or two mothers only registered for evacuation. But in that bombing which took place at night there was not the same anxiety because at each centre there were shelters up to full code standard in which they could spend the whole night. During that bombing we had no casualties. When we got to the stage of the flying bombs it was different and I made representations that we could not keep the women and children in London, but I was quite certain that they would not be parted. We found that they were anxious to go away; during the time that they were here there never was any idea of a concentration camp; they were free at any time to leave the centres, and some of them did. Some who were outside the centres preferred to join the scheme in the end in order to go to Northern Ireland. I have seen, and can let my right hon. Friend see, the notice that was put up in each centre at that time. I know that some of them thought that, if they went, they would be going home to Gibraltar quickly, though it was clearly stated that that was not the case. At that time 3,000 went back to Gibraltar and over 6,000 went to Northern Ireland; another 500 left for Gibraltar about September. They were free to go out and live as they liked in this country or to join the party that was being evacuated to Northern Ireland. They were very happy to go, and my right hon. Friend knows how happy they were in the first few months in Northern Ireland. They were delighted with their new surroundings.

Clothes were a difficulty, but they had a very generous supply through the W.V.S. Their luggage was delayed, but I am thankful to say that eventually they got it. I have been told that they had used all their clothing coupons before they went to Northern Ireland, but since then more coupons have become valid. Besides this, they got clothing through the W.V.S., and also second-hand waterproofs free without coupons. Shoes were difficult but we offered them wooden clogs free for two coupons. Work has also been a difficulty. In many cases where they were asked to help with the harvest I am sorry to say they did not do so. They could have helped the contractors in putting up huts and other buildings. The Ministry of Labour has to deckle whether they can be allowed to take work in England; that is not a matter for the Ministry of Health at all. In any case they cannot come to London while there is no accommodation for them. Some were allowed to take up work in Lancashire, but it was not a success. They complained of their billets, they complained of having to pay Income Tax, they did not get on with the other workers; some went away on their own and the rest had to leave.

I think we are all agreed that the camps in Northern Ireland are as good as they can be made. Transport is provided to the towns, and to technical colleges for the boys and girls; arrangements have been made for chapels and for priests to visit then; in the case of Jewish camps, for a synagogue. On the whole, we have made the camps as good as we could, but these people are away from home and they want to go back. We want them to go back, too, and we will do everything we can to get them back as soon as possible.