Explaining the terminology used in the Prehistoric Andalucia series of articles and exploring some of the more controversial conventions

By Nick Nutter | Updated 24 Aug 2022 | Andalucia | History |

Login to add to YOUR Favourites or Read Later

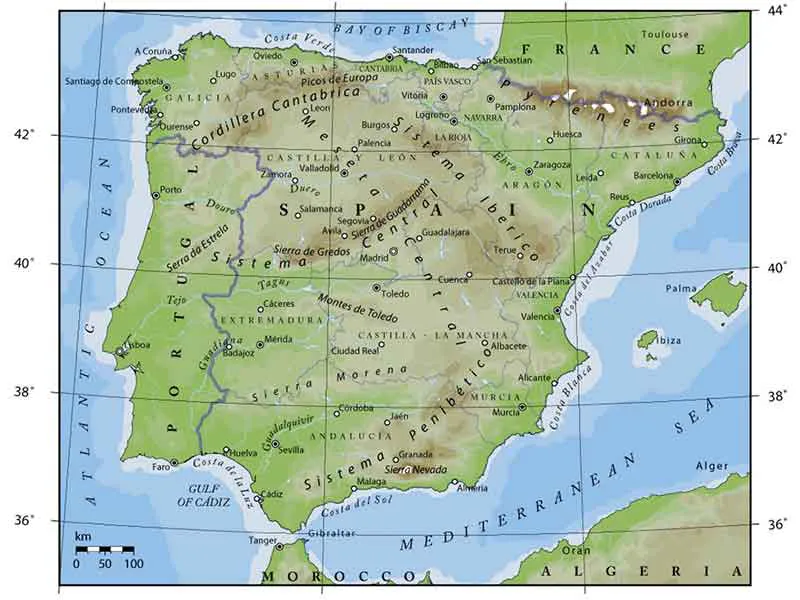

Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula is the westernmost extent of Europe. It includes the countries of Spain and Portugal. Andalucia is a semi-autonomous region in Spain in the south of the Iberian Peninsula.

In a clockwise direction, from the west Andalucia is surrounded by:

Portugal, Extremadura, Castilla-La Mancha, and Murcia. The British Overseas Territory of Gibraltar is a 2.5-kilometre long peninsula at the south end of Andalucia. The south western coast is on the Atlantic Ocean and the southern coast is on the Mediterranean Sea. The two oceans are separated by the Gibraltar Strait. 20 kilometres across the Gibraltar Strait is North Africa.

Modern names for areas, cities and towns will be used throughout. Until modern times, geography provided the boundaries, not lines on a map. So, although this is a prehistory of the area now known as Andalucia, it is inevitable that the events unfolding in surrounding areas will influence events in Andalucia. Interaction takes place across borders that did not exist in prehistoric times.

With a surface area of 87,507 sq kilometres, Andalucia is larger than the entire country of Austria (83,858 sq kilometres). It is approximately 500 kilometres from west to east at its broadest and 200 kilometres from north to south.

The region centres on the south west to north east running Baetic Depression, otherwise known as the valley of the Rio Guadalquivir. The river estuary is on the Atlantic coast and the well-watered valley is about 420 kilometres long and occupies 35,000 square kilometres.

To the north of the Baetic Depression, and forming its northern boundary, is a range of mountains called the Sierra Morena. They run northeast from the Atlantic coast in Portugal, across the top of the Baetic Depression and into Castilla La Mancha.

To the northwest of the Baetic Depression, the Rio Oriel runs off the Sierra Morena into the Atlantic Ocean at Huelva and the Rio Guadiana flows into the Atlantic Ocean at Ayamonte and forms part of the present day border between Andalucia and Portugal.

To the south of the estuary of the Rio Gualalquivir, also draining the Baetic Depression, is the Rio Guadalette that flows into Cadiz Bay and into the Atlantic Ocean.

South of the Baetic Depression, and forming its southern boundary, is a range of mountains. There are three parallel folds in the mountains, each running more or less west to east, the Cordillera Subbeticas, Cordillera Beticas and the Cordillera Penibetica. The range begins on the Atlantic coast at Punta Tarifa and runs east into Murcia.

To the east of the Baetic Depression an arc of low mountains, the Sierra de Segura, link the Sierra Morena to the Cordillera Subbeticas.

The Cordillera Penibetica range includes the highest mountains on the Iberian Peninsula, the Sierra Nevada.

The southern flanks of the Cordillera Subbeticas and Cordillera Penibetica fall into the Mediterranean Sea, leaving a thin coastal strip, that today is sometimes only a couple of kilometres wide, relieved by a few minor rivers that flow off the mountains into the Mediterranean Sea.

From west to east those rivers are:

The Guadiaro at Sotogrande

The Guadalhorce at Malaga

The Rio Velez at Torre del Mar

The Rio Higueron at Nerja

The Rio Verde at Almunecar

The Guadalfeo at Salobrena

The Rio Andarax at Almeria

The Almanzora at Villaricos

During the Last Glacial Period, and for some time afterwards, from about 120 kya to 7 kya, lower sea levels extended these rivers across a coastal plain that was up to five kilometres wide. The rivers, depending on their flow, created valleys, some deeper than others. For instance, in other countries, the Rivers Nile and Rhone created veritable canyons that are now submerged.

In Andalucia, a similar but smaller canyon was carved out by the Rio Guadalquivir flowing into the Atlantic and smaller ravines by the rivers Guadiaro, Guadalhorce, Guadalfeo and Almanzora, flowing into the Mediterranean. Rivers flowing straight off the mountains into the Mediterranean Sea, with no intervening coastal plain, did not create canyons.

The routes humans used to penetrate Andalucia were determined by the geography and the requirements of the humans. Hunter gatherers look for different landscapes to agriculturalists.

It is generally accepted that the first hunter gatherers approached Andalucia from the east.

Prehistorians will often, sweepingly, declare that the Iberian Peninsula was populated by people following a coastal route. This may be true of the Neolithic people using canoes, it is certainly not true for the original hunter gatherers.

Any journey along the coast from Malaga to Murcia will show that, in places, in the Nerja and Almunecar areas, at Adra, the Cabo de Gata, and north of Villaricos, the terrain comprises sheer cliffs rising to high mountains and backed by parallel lines of formidable Sierras. Even given the increased width of the coastal littoral during the depths of the Last Glacial Period, the coast from Almeria to Malaga generally remained precipitous and was not an easy landscape to traverse. Whoever passed down that way would have been forced to take wide diversions inland.

The first hunter-gatherers found routes through and between the mountains. Those same routes today carry the major roads into the region.

Following the ancient routes into Andalucia is an eye-opening experience, if only for the scenery. Even ‘easy’ routes would have provided challenges to parties on foot.

Approaching Andalucia from Murcia, there are basically two routes. The A 92N, through Baza to Guadix, Granada and thence into the Guadalquivir valley. A few secondary routes branch off giving access to the lesser valleys between the Sierras, such as the Almeria (on the A7) to Guadix route that passes between the Sierra Nevada and Sierra de Baza.

History, even prehistory, is about people. Our past determines who we are in the present. So, it is with Andalucia. The way of life today and the character of its people, have all developed over the last 45,000 years or so, since modern man arrived in the Iberian Peninsula. The Andalucia of the 21st century is a cumulative manifestation of everything that has occurred in the past. The present, what we see and experience today in Andalucia, has been influenced by geography, climate, geology, natural resources, immigrants and invaders. Teasing out those influences at any given point in the past is what makes history fun.

How people look at and understand history is changing. It is becoming more realistic, more like a stream flowing than a series of isolated events. For instance, the Copper Age; apart from the fact that the Copper Age starts and ends at different times in different places, we are still using copper. Only the methods of extraction, production and use have changed over time. The same goes for the Stone Age, we still use stone, the Bronze Age, the Iron Age and so on. So, in this account of the prehistory of Andalucia, we shall, where appropriate, identify how, by whom, when and where the various ages started, if we can, and how they developed.

For convenience, archaeologists have divided the prehistoric era into periods that existed at different times in different parts of the world.

Paleolithic refers to the Stone Age, the period of time in which stone tools developed. In the Mediterranean theatre those periods are as follows:

Lower Paleolithic - 1.4 mya to 200 kya.

Middle Paleolithic - 200 kya to 50 kya.

Upper Paleolithic - 50 kya to 20 kya

Epipaleolithic - 20 kya to10 kya

Holocene - 10 kya to present day

Epochs are slightly different in as much as they are global divisions of time, quite well defined.

The Pleistocene is a geological epoch that spans the world’s most recent period of repeated glaciations and extends from about 2.4 mya to 11.7 kya. It is further subdivided as follows:

Lower Pleistocene - 2.4 mya to 700 kya

Middle Pleistocene - 700 kya to 100 kya

Upper Pleistocene - 100 kya to 11.7 kya

Within the Upper Pleistocene there are the following periods:

Bolling -14.8 kya to 14.7 kya. A period of rapid warming that raised sea levels by up to 35 metres due to glacial melt.

Allerod - 14.7 kya to 13.2 kya. An oscillating period of cooling that took temperatures back to pre Bolling levels.

Younger Dryas - 13.2 kya to 11.7 kya. A period of generally rising temperatures and finally a rapid rise in temperatures signalling the end of the Pleistocene

In addition, you may come across the following terms:

Terminal Pleistocene Hunter Gatherers - Hunter gatherers to the end of the Younger Dryas

Mesolithic - Hunter Gatherers who lived after the Younger Dryas to about 5000 ya (In Iberia)

Neolithic - Beginning of agriculture about 7.5 kya (In Iberia)

The Mesolithic and Neolithic occurred at different times in different parts of the world, even in different parts of the Iberian Peninsula. Hunting and gathering was the predominant way of existing until the Neolithic people arrived in Andalucia about 6500 BC. However, hunting and gathering did not cease. As a method of obtaining food it diminished in importance, but it still goes on to this day, only the methods have changed. In fact, hunting is enjoying a revival in Andalucia as more and more people take up crossbows, bows and arrows and rifles to kill wild animals for food, wild boar, deer, rabbits and birds. Fishing and gathering molluscs have been primary methods of providing sustenance for coastal communities since before modern man arrived in the Iberian Peninsula.

‘Cultures’ and ‘traditions’ are words used when studying prehistory that often give the wrong impression. For instance, the term ‘Argar culture’. The Argar, and any other culture, is a collection of practices, rituals and social engagement, often expressed or identified by the use or manufacture of physical objects. It is sometimes the case that the finder of an artefact, a piece of pottery for instance, automatically but falsely, assumes the presence of an entire culture.

Each element of the ‘culture’ may have been introduced at a different time and in a different way and, most importantly, to different degrees in any given area. So, to say or imply that the Argar culture became embedded in what is now Almeria, parts of Granada and Jaen provinces and was in place between two dates, may give the wrong impression. The full suite of components that make up the culture known as Argar may have existed in a core area or areas with elements of that culture identifiable in other areas before, during or after the accepted period of existence of the culture.

The various toolmaking traditions that appeared and have been identified as occurring in the Iberian Peninsula, the Aurignacian, Gravettian, Solutrean and Magdalenian, are just convenient labels to describe a succession of tools and implements that gradually improved. These became more efficient and were more suited to the climate at any given time. They were developed to deal with a specific opportunity, or enhanced chances of survival or, incredibly, quality of life. Elements of the earlier traditions appear in the later.

Andalucia is large enough in area, and diverse enough in geography, that two or more ‘cultures’ or ‘traditions’ could, and often did, exist at the same time. Those cultures affected each other, ideas were transmitted between groups, so the ‘cultures’ blurred at the edges.

Finally, as with the Ages and Eras. Cultures did not spring, fully formed, into existence at a given time. They developed. Unlike the Ages and Eras, cultures often did end quickly and often suddenly whilst others developed into other manifestations and therefore earned another ‘cultural label’.

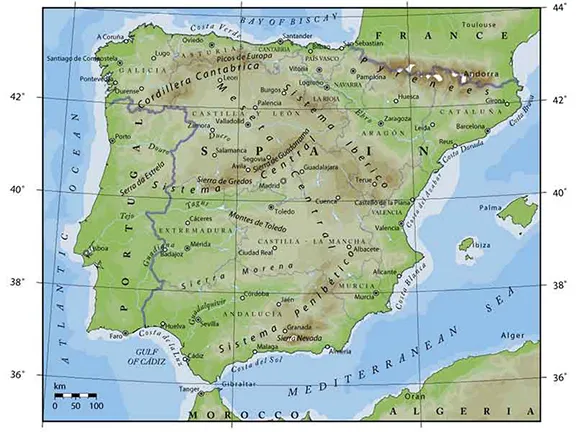

Illustration by Paul Mazza . The Mediterranean during the peak of the Last Glacial Maximum (approximately 18 kya). The dotted line represents the present-day coastline.