The Spanish Civil War was the first war fought in Europe in which civilians became targets en masse, through bombing raids on towns and cities.

By Nick Nutter | Updated 24 Apr 2023 | Andalucia | History |

Login to add to YOUR Favourites or Read Later

Spain Divided September 1936 Nationalists - Pink Republicans - Blue

From the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War on the 17th July 1936, until its conclusion on the 1st April 1939, the population of Andalucia was divided in its loyalties between the rebel Nationalists and the legitimate Republican government.

In the decades before 1936, Spanish life and politics had become increasingly polarised. On one side were the Nationalists who comprised most Roman Catholics, about half of the military, the majority of the landowners who were mainly nobles and from high-ranking families, and many businessmen. On the other side were the Republicans who were blue collar workers, agricultural labourers and, surprisingly, many of the educated middle class who saw themselves as badly represented.

On a political level, there were extreme parties on the far right including the Fascist-oriented Falange and the far-left militant anarchists. Other parties fell somewhere between the extremes, from monarchism and conservatism through liberalism to socialism, including a small communist movement divided among followers of the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin and his arch-rival, Leon Trotsky.

A succession of governmental crises culminated in the elections of February 16, 1936, which brought to power a Popular Front government supported by most of the parties of the left and opposed by the parties of the right and what remained of the centre – a Republican Government.

Shortly after the Popular Front's victory, various groups of officers began discussing the prospect of a coup. It would only be by the end of April 1936 that General Emilio Mola would emerge as the leader of a national conspiracy network. The Republican government acted to remove suspect generals from influential posts. Franco was sacked as chief of staff and transferred to command of the Canary Islands. Manuel Goded Llopis was removed as inspector general and was made general of the Balearic Islands. Emilio Mola was moved from head of the Army of Africa to military commander of Pamplona in Navarre. General José Sanjurjo, in exile in Portugal, became the figurehead of the operation.

The well-planned military uprising began on the 17th July 1936, in Morocco and in garrison towns throughout Spain. The uprising was mainly planned by the three generals, Emilio Mola y Vidal, 1st Duke of Mola, Grandee of Spain, José Sanjurjo y Sacanell and Manuel Goded Llopis.

The original plan was for a swift coup d’état with the military taking over control of the major cities in Spain. The coup was supported by military units in Morocco, Pamplona, Burgos, Zaragoza, Valladolid, Cádiz, Córdoba, and Seville. However, rebelling units in some of the most important cities—such as Madrid, Barcelona, Valencia, Bilbao, Huelva, Málaga, Jaén and Almería —did not gain control, and those cities remained under the control of the government.

General Francisco Franco and soldiers loyal to him, the Army of Africa, seized a Spanish Army outpost in Morocco. In Spain, other Nationalist troops seized other garrisons. By the 21st July, the Nationalist rebels had achieved control in Spanish Morocco, the Canary Islands, and the Balearic Islands (except Minorca) and in the part of Spain north of the Guadarrama mountains and the Ebro River, except for Asturias, Santander, and the Basque provinces along the north coast and the region of Catalonia in the northeast.

By the end of July 1936, in Andalucia, the Republicans retained control of Huelva, Málaga, Jaén and Almería whilst the Nationalists had taken Cádiz, Seville, Granada, and Córdoba.

The coup had failed to achieve its objectives, the country was split and the uprising became a civil war. The Nationalist generals declared themselves the legal government with support in the Republican government in Madrid from a number of conservative groups, including CEDA, monarchists, including both the opposing Alfonsists and the religious conservative Carlists, and the Falange Española de las JONS, a fascist political party.

General Francisco Paulino Hermenegildo Teódulo Franco Bahamonde

The initial few weeks of the civil war were not kind to the generals leading the original coup.

José Sanjurjo y Sacanell began the coup of 1936 from a self-imposed exile in Portugal. He had already led a coup attempt in August 1932 for which he had been sentenced to death, later commuted to life imprisonment and pardoned in 1934. Sanjuro expected to be appointed commander-in-chief of the Nationalist faction and, on the third day of the war, flew in a small plane from Portugal back to Spain. He was killed when the plane crashed on the 20th July 1936.

Mola assumed command of the Nationalist forces in the north of Spain and appointed Franco commander of the southern forces.

Goded meanwhile, was busy taking the Mediterranean islands of Mallorca and Ibiza before turning his attention to Catalonia, one of the most industrialised regions in Spain and staunch supporters of the parties of the left in the Republican government. His insurrection in Barcelona failed and Manuel Goded Llopis was captured on the 11th August 1936 and executed by the Republican government the following day. Goded’s death removed one of the key personal and political rivals to the movement's eventual leader, Franco.

Republican forces also killed several of Franco’s other potential rivals, including monarchist politician José Calvo Sotelo and the fascist politician José Antonio Primo de Rivera.

On October 1, 1936, Franco was named commander in chief of the armed forces and head of the rebel Nationalist government and set up a government in Burgos.

When he was promoted to the rank of Brigadier General in 1926, at 33 years of age, Franco became the second ever, youngest General, only Napolean was promoted to this rank at a younger age (24). By the time his dictatorship ended, in 1975, Franco was the longest ever ruling dictator.

Mola died on 3 June 1937, when the aircraft in which he was travelling flew into the side of a mountain in bad weather. The deaths of Sanjurjo, Mola, and Goded left Franco as the pre-eminent leader of the Nationalist cause.

Fiat CR 32 - Nationalist Airforce

The Nationalists received aid from Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, despite a non-intervention agreement signed in August 1936 between France, Britain, the Soviet Union, Germany, and Italy.

Benito Mussolini in Italy was quick to support Franco and sent Spain more than 700 airplanes, including the Fiat CR.32 biplane, and troops during the conflict. But it was Germany that was most instrumental in the war. Only days after the war erupted, Franco had sent a request for help to Adolph Hitler.

For Germany, the Spanish Civil War came at an opportune time. The nation was initiating a rearmament program, in violation of the World War I peace treaty. A war in Spain would distract the world’s governments from this transgression. Plus, Spain had raw materials that Germany could use. Hitler also liked the idea of threatening France with a Fascist government to its south. But most importantly, Spain would provide an opportunity to test equipment and train troops. Although Hitler was careful not to send enough troops to make the world perceive them as a combatant nation, 19,000 German "volunteers" gained valuable combat experience in Spain. Because the Nationalists already had strong army support, Germany mostly sent over aviators from the Luftwaffe.

Messerschmitt Bf 109 - Condor Legion

The Germans were organized into the Condor Legion that was equipped with the most modern airplanes and a specially trained staff. Many of the newest airplanes were tested in real combat situations, among them the Heinkel He.111, and the Messerschmitt Bf.109. The Legion was divided into bomber, fighter, reconnaissance, seaplane, communication, medical, and anti-aircraft battalions, and included an experimental flight group. The chief of staff was Colonel Wolfram von Richthofen, a cousin of "The Red Baron."

Only a handful of Americans actually fought for the Nationalist side but one of Franco’s staunchest allies was Texaco’s chief executive officer, Torkild Rieber.

Rieber admired Hitler and said he preferred doing business with autocrats. From his office in New York, Rieber blatantly violated United States neutrality acts and illegally sold the Nationalists discounted oil on credit and transported the fuel in his company’s own tankers. His worldwide network of employees passed along the whereabouts of Republican-bound oil shipments, thereby leaving them open to attack.

Juan Negrín

The Republican government, after September 1936, was headed by the socialist leader Francisco Largo Caballero. He was followed in May 1937 by Juan Negrín, also a socialist, who remained premier throughout the remainder of the war and served as premier in exile until 1945. The president of the Spanish Republic until nearly the end of the war was Manuel Azaña, an anticlerical liberal.

The Republicans suffered from internecine conflict from the outset. On one side were the anarchists and militant socialists, who viewed the war as a revolutionary struggle and spearheaded widespread collectivization of agriculture, industry, and services; on the other were the more moderate socialists and republicans, whose objective was the preservation of the Republic. These disputes between the parties severely compromised the Republican effort.

Seeking allies against the threat of Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union had embraced a Popular Front strategy, and, as a result, the Comintern directed Spanish communists to support the Republicans.

The Comintern stands for the Communist International, also known as the Third International. It was a Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism, took its orders from Moscow and took an active role in promoting communism by legal and illegal means and by peaceful and armed actions in any country deemed vulnerable.

The Republicans received aid from the Soviet Union as well as from the International Brigades, composed of volunteers from Europe and the United States. About 40,000 foreigners fought on the Republican side in the International Brigades largely under the command of the Comintern, and 20,000 others served in medical or auxiliary units.

About 2,800 Americans—many of whom had never fired a gun—volunteered for the Republican cause. The so-called Abraham Lincoln Battalion was a diverse group and included a vaudeville acrobat, a rabbi and the first African American ever to lead white troops into battle. The Republican leaders treated the Abraham Lincoln Brigade as cannon fodder. “We are shock troops,” a wounded American reportedly said from his hospital bed. “The Republic had to push some meat out there in front, and we were elected.” By the time the Lincolns departed Spain in October 1938, more than a quarter of them had perished.

Polikarpo I-5 - Patrolla Americana

A group of three Americans pilots formed the Patrolla Americana, which eventually grew into a unit of 20 pilots. They flew Russian biplanes, sturdy I-15s designed by the Soviet Union’s “King of Fighters,” Nikolai Polikarpov. Painted red bands on the wings and fuselage marked these craft as belonging to the Spanish Republic air force.

The Soviet Union, recognizing a potential Communist nation threatened by fascism, was quick to offer aid, including equipment, soldiers, and senior advisors. Many of their planes, including the Polikarpov I-15 and I-16, formed the backbone of the Republican Air Force. These sturdy, but obsolete, biplanes were totally outclassed by the Messerschmitt Bf 109 flown by the Condor Legion.

As a gesture to protect itself from being surrounded on three sides by Fascist nations, France provided some aircraft and artillery.

The Spanish Republican Navy comprised some 20,000 men and about 80 warships including two battleships, seven cruisers, seventeen destroyers, five gunboats, nine coastguard vessels, eleven torpedo boats and about a dozen submarines. It was based at El Ferrol, covering the Cantabrian Sea, Cádiz to cover the Atlantic coast of Spain and Cartagena to cover the Mediterranean.

There is no indication that the navy took part in planning the army led coup. However, the navy was as split politically as was the general population. Many of the officers, particularly those of higher rank, favoured the Nationalists whilst the majority of the lower ranking officers and other ranks were loyal to the Republican government.

On the 14th July 1936, a message had been transmitted from the Ministry of Marine in Madrid to the heads of the three naval bases warning them to ‘prevent extremists of one side or other from spreading propaganda among personnel under your command.’ They were ordered to signal back to Madrid whether ‘personnel of all classes can be trusted to obey your orders’. Naval officers who were thought to be of dubious loyalty to the Republican government were asked to resign.

The loyalty of officers and men was soon tested. On the 18th July, two days after the attempted army coup, a signal was sent from the Minister of Marine to the commanding officers of the four Spanish destroyers and a gunboat based at Ceuta and Melilla, ordering them to stop any ships bringing Franco’s troops across the Gibraltar Strait from Africa. In addition, the signal ordered them to open fire on Nationalist camps, barracks or gatherings.

At Melilla, Captain Fernando Bastarreche, a staunch supporter of Franco, tried to persuade his crew that they should not follow the orders. The crew were not responsive to his arguments but neither did they relish firing on their own countrymen. In the end the two destroyers at Melilla sailed to the Republican port of Cartagena.

At Ceuta, it was a different story. The destroyer Churruca embarked four hundred soldiers from Franco’s Army of Africa and, together with the passenger ship Ciudad de Algeciras, set off for Cádiz whilst the mail steam-packet, Cabo Espartel, carrying a battalion of Regulars, headed for Algeciras.

The Spanish Republican Navy was in turmoil. Officers rebelling against the Republican state they had vowed to serve, provoked mutiny amongst the crews who were determined to follow the orders of the Republican government. Republicans and Nationalists fought for control of ships and bases. The Nationalists took the naval bases at El Ferrol, La Coruna, San Fernando near Cádiz and Palma de Mallorca. The Mediterranean bases from Málaga to Barcelona and those on the northern Biscay coast remained in the hands of the Republicans.

Republican crew members seized the cruisers Libertad and Miguel de Cervantes from officers who wanted to go over to the Nationalist cause. On the Cervantes, the officers resisted to the last man and were either shot whilst resisting or executed later at Cartagena. Overall, more than a third of Spanish naval officers were murdered or executed depending on your point of view.

On the 19th July, just off the coast of Portugal, sailors loyal to the Republic stormed the bridge of the España class battleship, ‘Jaime I’. They shot and killed the Nationalist Captain Aguilar and Lieutenant Cañas and took over the ship.

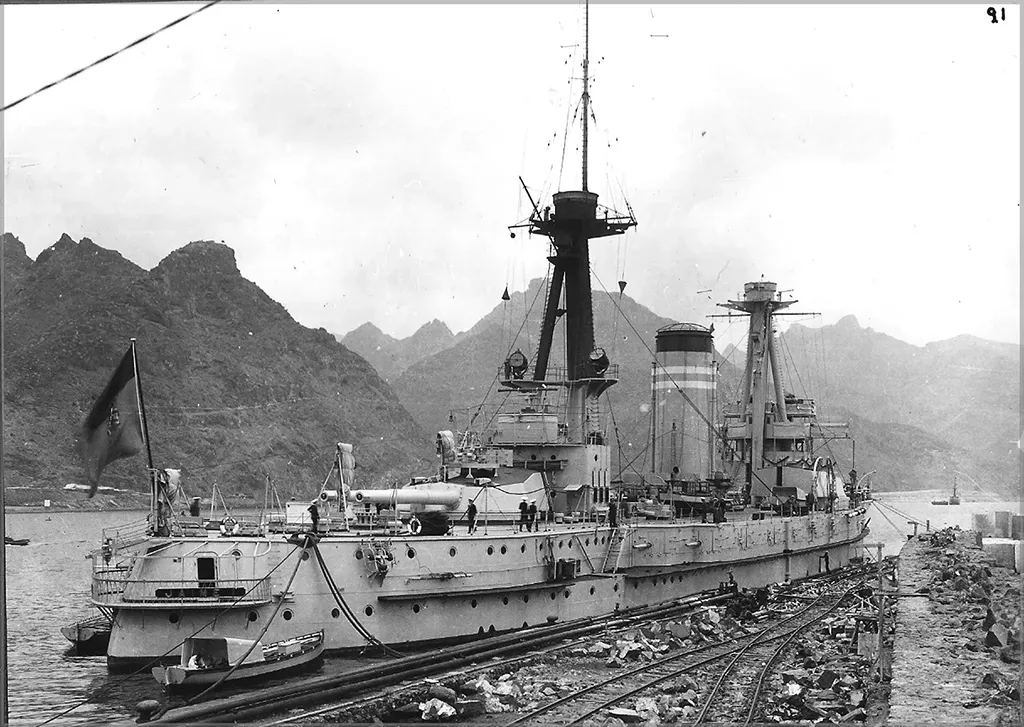

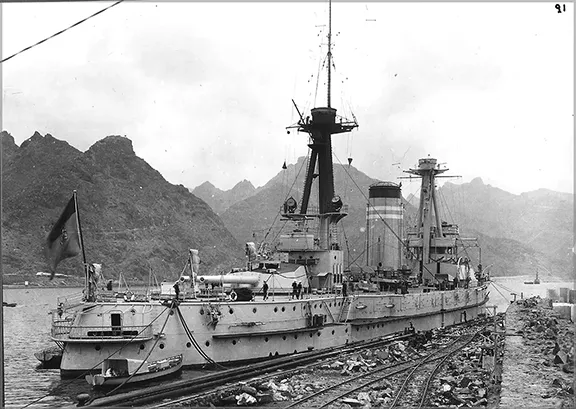

Battleship Jaime I

When the dust settled, the Republic boasted a large fleet with the dreadnought battleship ‘Jaime I’, cruisers ‘Libertad’, ‘Cervantes’ and ‘Méndez Núñez’, 12 destroyers, all the submarines from the bases of Cartagena and Mahon and most torpedo and auxiliary boats.

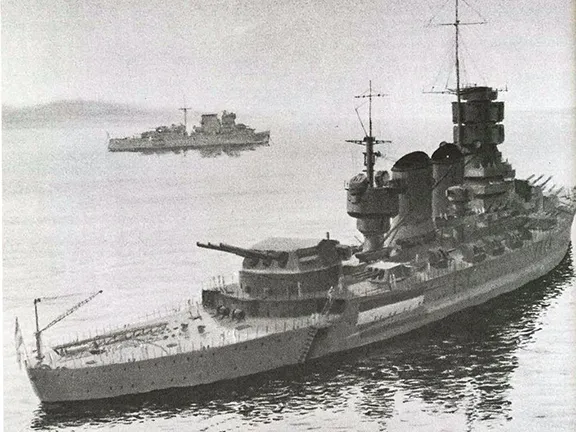

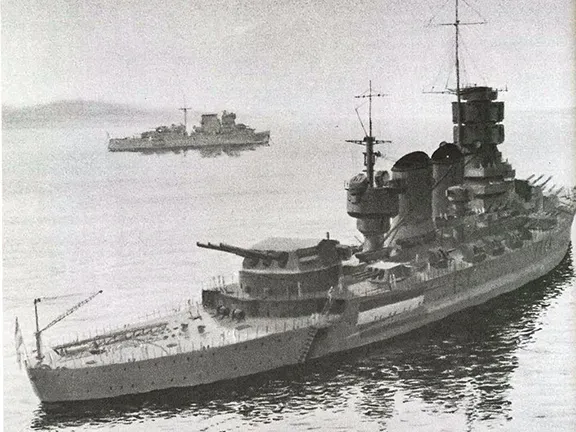

Battleship Espana

The Nationalist fleet had only one cruiser, the ‘Almirante Cervera’, the old battleship ‘España’, the destroyer ‘Velasco’ and the cruiser ‘República’ that was immediately renamed ‘Navarra’. The modern cruisers ‘Canarias’ and ‘Baleares’ were hurriedly commissioned at the beginning of the war.

In the first days of the war, the Republican fleet controlled the Mediterranean and the Gibraltar Strait while the Nationalist ships ruled in the Cantabrian Sea.

At the outbreak of the war, the armed forces were fairly evenly matched with about 87,000 troops remaining loyal to the Republic and 77,000 joining the Nationalist cause. The Nationalist forces included the most disciplined and battle-hardened unit within Spain and its territories, the 8,000 strong Army of Africa led by General Franco.

The stage was set for one of the most vicious civil wars of the 20th century and Andalucia was to be the stage for some of its bloodiest battles and most heinous atrocities.