The Almoravids soon succumbed to a pleasure loving lifestyle and found it difficult to resist Christian incursions into al-Andalus. They called upon the Almohads to rescue them.

By Nick Nutter | Updated 11 Apr 2023 | Andalucia | History |

Login to add to YOUR Favourites or Read Later

Templar Castle Tomar

In 1147, the last Almoravid king, Ishaq ibn Ali, was killed in Marrakesh by the forces of the Almohad Caliphate who thereby replaced the Almoravids as the ruling dynasty in North Africa and al-Andalus. Two years prior to that event, in 1145, the clerics in al-Andalus had invited the Almohads into al-Andalus to help them oppose the Christian advances and counter the pleasure loving lifestyle to which the Almoravid kings of the taifas had succumbed. History was repeating itself after only sixty years.

Order of Santiago

The Almohad forces arrived in 1145 and immediately set about re-uniting the taifas into one entity. The Almohads, like their Almoravid predecessors in 1086, disapproved of the life-style of the Andalusis, and followed an even stricter and more orthodox interpretation of the Qur’an and were more militant in rejecting material pleasures. They were also more jihadist and far more intolerant of Christians and Jews than were the Almoravids and demanded conversion to Islam as the price for remaining in al-Andalus. Predictably many Christians and Jews abandoned al-Andalus for the Christian kingdoms to the north and, after 1149, to a new Muslim kingdom carved out by an aristocratic Mozarab, Muhammad ibn Mardanís.

The Almohads met little opposition to their take over of al-Andalus apart from in Murcia and Valencia where Muhammad ibn Mardanís, better known by his Christian nickname of ‘El Rey Lobo’ (King Wolf), established a kingdom for himself from about 1149 until his death in 1172 AD.

Order of Calatrava

El Rey Lobo hated the Almohads. Being from a Mozarab family he was a Christian first and Muslim second. He spoke both Arabic and the Spanish of the time, wore Christian clothes, often used Christian soldiers alongside his Muslim troops, and encouraged Christians to settle in the lands he controlled. He was not averse to paying tributes to Ramón Berenguer IV and his son Alfonso II of Aragon to ally himself with them and guarantee peace on his frontier with the Christian states whilst he made inroads into the Almohad territories.

Lobo made Murcia his capital city. From there, with the support of his father-in-law Ibrahim ibn Hamushk of Jaén, Lobo extended his domains to Jaén, Baza and Guadix (1159), conquered Écija and Carmona (1158-1160), threatened Córdoba and encircled Seville , wreaking havoc on the Almohad dynasty. After the conquest of Jaén, ibn Hamushk was put in charge of their government, as well as those of Baza and Úbeda. In 1160, while they surrounded Córdoba, El Rey Lobo and his father-in-law managed to kill the Almohad governor. They were at the height of their power. An Almohad counterattack in 1161 lost them Carmona but then there was a four year hiatus whilst the Almohads developed a strategy.

Over the next few years, Murcia became a rich and prosperous city, its currency, the ‘lupine morebetinos’, was a benchmark throughout Europe. Prosperity was based on agriculture and ceramics. The extensive hydrological network of dams, water wheels, ditches and aqueducts that powered the grain mills in Murcia are still evident in that city alongside the River Segura.

Such impertinence could not be allowed to continue. In 1165, the Almohads assembled a large army with conscripts from North Africa. Over the next seven years until his death in 1172, El Rey Lobo lost all the territories he had gained and was betrayed first by his father in law, then a cousin, followed by a brother in law, who all controlled towns within the mini empire, and finally, his own son Hilal, who pledged allegiance to the Almohads in return for governorship of Murcia.

To partially reassure the Andalusi that they were not to be considered vassals of Marrakesh, the Almohads made Seville a co-capital. This move also made it easier to deal with the Christian forces and rebels such as El Rey Lobo since decisions could now be made in al-Andalus rather than having them passed along to Marrakesh and the consequent delay whilst waiting for a response.

Order of Alcantara

In the north, the Christians occupied five kingdoms, Castile, León, Navarre, Portugal and Aragón but they were far from united. Any thought of unity was undermined by territorial disputes, mutual suspicion and open hostilities between the five kingdoms. Hostility between Castile, León and Navarre was particularly intense.

In 1195, Alfonso VIII of Castile was severely beaten by the Almohads at the Battle of Alarcos (about halfway between Granada and Madrid). Following the defeat, the kings of León and Navarre attacked Castilian lands in revenge for perceived affronts. Even personal slights could cause defection. A Castilian noble, Pedro Fernández de Castro, fought for the Almohads in the battle of Alarcos following a quarrel with Alfonso VIII.

His defeat at Alarcos only seems to have made Alfonso more determined to rid the Iberian Peninsula of the Almohads, his efforts only frustrated by the disunity of the Christian kingdoms. In 1197, help once again came from over the Pyrenees, as it had a century before.

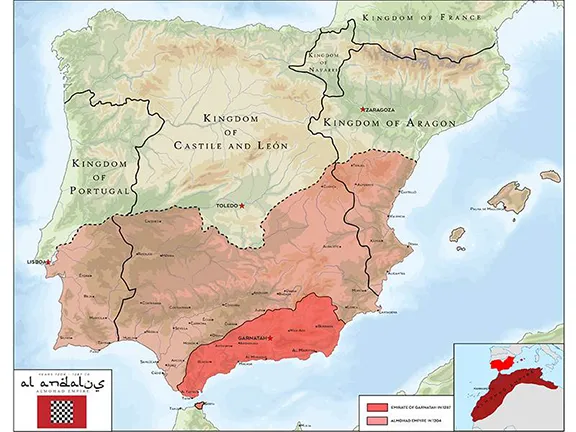

Territory controlled by El Rey Lobo

Pope Celestine III issued a call for a crusade in the Iberian Peninsula. His call was repeated by his successor, Pope Innocent III in 1206 AD.

Celestine’s motivation for such an action was the loss of Jerusalem in 1187 to the Muslim forces of Saladin and the failure of the 3rd crusade in 1189, to retake the city. Defeat at the eastern end of the Mediterranean had to be made good at the western end.

Celestine also threatened the various kings in the Christian north of the Iberian Peninsula with excommunication unless they forgot their differences. The Mediaeval equivalent of banging their heads together. One result of this proclamation was the marriage of the Leónese king, Alfonso IX, to the Castilian princess, Berenguela in 1197.

Almohad Decline

In response to the call for a crusade, soldiers arrived from France and Italy as well as Aragón and Navarre to help the Castilians. Portugal and León were still in dispute and did not participate in the battle of Las Navas de Tolosa led by Alfonso VIII of Castile that, in 1212 AD, turned the tide for the Christian side,. The French contingent decided to withdraw prior to the main battle, disgusted at the lenient treatment meted out on vanquished Muslims by the triumphant Christians during the many minor skirmishes that preluded the battle. Five hundred years of contact between Muslims and Christian had altered the perspective of the belligerents.

During the Almohad period, from being primarily a political power struggle with religious differences ignored or of little consequence, the Reconquista became first and foremost a battle of ideologies with the acquisition of land, power and money a reward. And that led to the founding of religious orders in the Iberian Peninsula.

The most famous Christian military order was the Knight’s Templar, formed to defend Jerusalem in 1119 AD. They also received endowments in the Iberian Peninsula, especially Aragón, and Portugal. The Templar castle and church at Tomar is a magnificent example of Knights Templar sponsored building of this time.

The Templars in the Iberian Peninsula were soon eclipsed by home grown religious brotherhoods. The three most important orders were; the Order of Calatrava (founded in 1158), the Order of Alcántara (founded in 1165) and the Order of Santiago founded in 1170 AD. These monks of war were not only knights, they had also taken the monastic vows of poverty, chastity and obedience. With no political axe to grind and a mission to defend Christianity against Islam, they were viewed as the ideal embodiment of the crusading spirit. The Knights of the Orders played an increasingly important role in defending the frontiers of Christendom and were rewarded with lands and castles that became a source of economic and political power.

Contrary to popular belief, the Order of Santiago was not set up to protect pilgrims on the road to Santiago de Compostela. It was founded in Cásares in Extremadura and takes its name from the archbishop of Santiago who funded the first knights. The archbishop was made an honorary member of the order and provided a standard of the saint. The Order’s motto reads, Rubet ensis sanguine Arabum: “The sword runs red with the blood of the Arab”, clearly indicating the purpose of the Order.

Tolosa is in the present day province of Jaén, just south of the Sierra Morena mountain chain that runs from west to east and acts as a natural defensive barrier between the central massif and the fertile lowlands of the Guadalquivir valley. Once breached there were no natural obstacles facing the Christians. The defeat of the Muslims at the battle of Las Navas de Tolosa also created a power vacuum in al-Andalus that once again broke apart into several taifas, each competing with the other. The two predominant taifas had radically different policies.

Muhammad ibn Hud of Murcia (1228–38) emphasized resistance on the part of the Muslims against the Christians whilst Muhammad I ibn al-Ahmar, who ruled in Granada from 1238 – 1273 AD acknowledged himself to be a vassal of the king of Castile.

The Christian advance was rapid. Córdoba fell to Ferdinand III of Castile-León in 1236, Valencia was taken by the Aragonese in 1238 and the Algarve went to the Portuguese in the 1240s. (The border between Spain and Portugal has remained essentially unchanged since this time making it the oldest frontier in Europe, and the longest). In 1243, Murcia was taken by the Castilians and in 1248 Ferdinand III rode into Seville. Only the kingdom of Granada remained in Muslim hands.

The final irony of this period of the Reconquista is that Ferdinand III was helped in his sieges and conquests of both Córdoba and Seville by Muslim troops from Granada. Politics again triumphing over religion. As a reward, Muhammad I ibn al-Ahmar was allowed to retain the kingdom of Granada that extended over the modern day provinces of Málaga, Granada and Almeria.

The Nasrid dynasty, founded by Muhammad ibn al-Ahmar in Granada, endured for two and a half centuries.

The Emirate of Granada coalesced from the break up of the taifas and the compression of al-Andalus into a much smaller area.

Abu Abdullah Muhammad ibn Yusuf ibn Nasr took power in his native Arjona in 1232 when he rebelled against the de facto leader of al-Andalus, Ibn Hud. During this rebellion, he was able to take control of Córdoba and Seville briefly, before he lost both cities to Ibn Hud. Forced to acknowledge Ibn Hud's suzerainty, Muhammad was able to retain Arjona and Jaén. In 1236, he betrayed Ibn Hud by helping Ferdinand III of Castile take Córdoba. In the years that followed, Muhammad was able to gain control over the southern cities, including Granada (1237), Almería (1238) and Málaga (1239). In 1244, he lost Arjona to Castile. Two years later, in 1246, he agreed to surrender Jaén and accept Ferdinand's overlordship in exchange for a 20-year truce.

Further reading and references

Dodds, Jerrilynn, Menocal Maria Rosa, Balbale Abigail K The Arts of Intimacy: Christians, Jews, and Muslims in the Making of Castilian Literature New Haven, London 2008.

Fletcher, Richards Moorish Spain London 1992

Hindley, Geoffrey The Crusades: Islam and Christianity in the Struggle for World Supremacy London 2003

Lomax, Derek The Reconquest of Spain London & New York 1978

Lowney, Chris A Vanished World: Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Medieval Spain Oxford 2006

O’Shea, Stephen Sea of Faith: Islam and Christianity in the Medieval Mediterranean World Vancouver, Toronto 2006

Smith, Colin Christians and Moors in Spain, II, 1195-1614 Warminster, England 1989.