Every year, on the 28th February, the citizens of Andalucia celebrate el Dia de Andalucia, Andalucia Day.

By Nick Nutter | Updated 5 Mar 2022 | Andalucia | Events |

Login to add to YOUR Favourites or Read Later

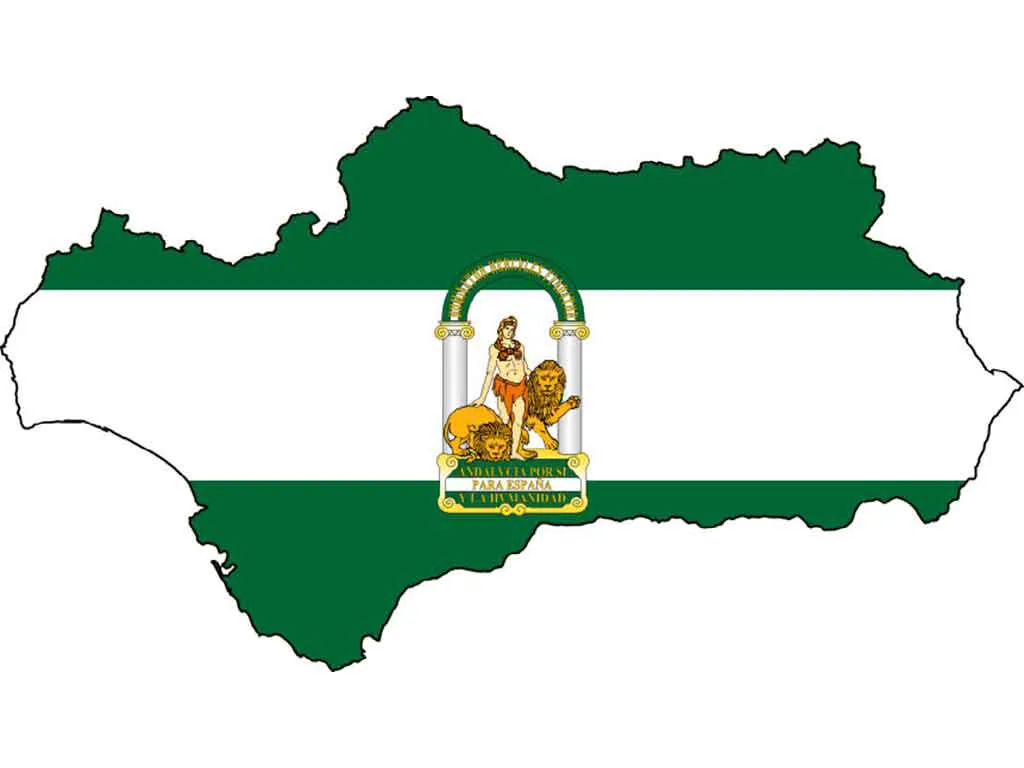

Dia del Andalucia Flag and Emblem

Every year, on the 28th February, the citizens of Andalucia celebrate el Dia de Andalucia, Andalucia Day. Green and white flags appear on public buildings and adorning houses and apartments. Parades and street parties are held in towns and villages throughout the region to commemorate the referendum on the Statute of Autonomy of Andalusia, in which the Andalusian electorate, on the 28th February 1980, voted for the statute that made Andalusia an autonomous community of Spain. The fiercely proud Andalucians, although not quite as fierce as the Catalonians or Basque people, eventually gained a degree of autonomy from the central government in Madrid. Gaining autonomy was a long, hard road that started in 1479 when the entire Spanish territory was only nominally united under one crown.

Although supposedly united in 1479, the Spanish territory consisted of a hodgepodge of crowns, kingdoms, principalities and dominions, each with its own legislative, judicial and fiscal authority. They all had their own customs, laws and currencies. Many had their own language. One territory, the Balearic Islands, was even forgotten entirely until 1588 when the islands were captured by the Turkish Admiral Piyate Pasha and the islanders petitioned King Philip II of Spain to help them defend themselves against repeated attacks by pirates. The petition brought the islands to the notice of the crown who realised that a source of taxes was being lost and the previously independent, if only by neglect, islands became part of Spain.

The land-owning oligarchy in Spain were naturally reluctant to relinquish their power and income and, until the 19th century, neither the crown nor any central government, were powerful enough to take on the establishment that consisted of noble families, the Catholic church and elements of the armed forces. It was not until 1833 that Spain was divided into 49 provinces (there are 50 today) and, even then, it was a legislative measure designed to transmit policies formulated in Madrid to the nation. In other words, an effort to impose some centralisation on the country. The measure was a contributing factor to the outbreak of the First Carlist War (1833 – 1840) that, according to historian Bradley Smith, ‘…was fought not so much on the basis of the legal claim of Don Carlos, [who claimed the throne of Spain after the death of his older brother King Ferdinand VII in 1833] but because a passionate, dedicated section of the Spanish people favoured a return to a kind of absolute monarchy that they felt would protect their individual freedoms (fueros), their regional individuality and their religious conservatism’.

Over the following eighty years, the political scene in Spain remained volatile with political parties from the far left to the far right competing for power. Most times they were hindered in their attempts to impose order on Spain by a hereditary monarch that was at times absolute and at others liberal and a nobility clinging to their power and privileges in what was still to all intents, a feudal society. In the meantime, in northern Europe, the industrial revolution was underway. Abroad, Spain was losing her colonial territories, and the income from them, at a faster rate than any other Empire before or since. Economically, Spain slipped further behind other European countries.

In the years leading up to the First World War, Spain saw two further civil wars, the Second Carlist War between 1846 and 1849, and the Third Carlist War between 1872 and 1876. Her monarchy swung between the absolute reign of Ferdinand VII to the constitutional monarchy of Isabella II, an elected monarchy under Amadeo I, no monarch at all during the republican period 1873 – 74, then back to a constitutional monarchy ruled by the House of Bourbon.

But the concept of autonomous regions persisted.

In 1913, Blas Infante Pérez de Vargas, a politician born in Casares, Malaga province, later to become known as Padre de la Patria Andaluza’, ‘Father of Andalucia’, initiated an assembly at Ronda. The assembly adopted a charter based on the autonomist ‘Constitución Federal de Antequera’ written in 1883 during the First Spanish Republic. Infante introduced the distinctive Andalucian flag, and an emblem for Andalucia that includes the Pillars of Hercules, designed by himself.

During the Second Spanish Republic (1931 – 39), the Andalucismo was represented by the Junta Liberalista, a federalist political party led by Infante.

Meanwhile, in 1914, limited autonomy was granted to the Commonwealth of Catalonia. It was abolished in 1925 and granted again during the Second Republic in 1932. The Constitution of 1931 laid the foundations for Spain to be divided into ‘autonomous regions’. By 1936, when the Spanish Civil War erupted, only Catalonia, Galicia and the Basque Country had approved ‘Statutes of Autonomy’.

Blas Infante, along with several other political figures, was executed in 1936 when Franco’s forces took Seville.

Franco instigated Martial Law until the end of the Civil War in 1939 and then a dictatorial regime until his death in 1975. Under Franco, centralism was vigorously enforced as a way of preserving the "unity of the Spanish nation". The Generalitat of Catalonia was abolished in 1939 and the president Lluís Companys, was tortured and executed on 15 October 1940 for the crime of 'military rebellion'.

Franco died in 1975 and Spain entered into a phase known as ‘transition towards democracy’. In 1977, a democratically elected government, the Cortes Generales, acting as a Constituent Assembly, set about transitioning Spain from a unitary centralized state into a decentralized state. The result was the Constitution of 1978 that led to the Referendum of the Andalucian people in 1980. Andalucia became an autonomous community under the 1981 Statute of Autonomy known as the ‘Estatuto de Carmona’.

Article 1 of the 1981 Statute of Autonomy justifies autonomy based on the region's "historical identity, on the self-government that the Constitution permits every nationality, on outright equality to the rest of the nationalities and regions that compose Spain, and with a power that emanates from the Andalusian Constitution and people, reflected in its Statute of Autonomy".

Even then it was a close run thing. On the 28th February 1981, exactly one year after the referendum in Andalucia, Lieutenant-Colonel Antonio Tejero led 200 armed Civil Guard officers into the Congress of Deputies during the vote to elect a President of the Government. This was the attempted coup d’etat of 1981 when seditious elements of the army and far right tried to impose a government committed to once again centralising Spain. Only the intervention of King Juan Carlos, who believed, rightly, that his military leaders were loyal to himself and the Constitution, prevented the coup from succeeding and thereby causing the autonomous community of Andalucia to be stillborn.

In 1982, article 3 of the 1982 Statute of Autonomy for Andalucia stated: ‘Andalucia will have its own emblem, approved de jure by its Parliament, in which the following legend shall appear: "ANDALUCÍA POR SÍ, PARA ESPAÑA Y LA HUMANIDAD" (Andalusia by herself, for Spain and for Humankind), taking into account the agreement adopted by the Assembly of Ronda of 1918.’

It took Spain nearly 500 years to progress from a decentralised feudal state, ruled by various nobles, some loyal to the crown, others not so loyal, via a period of chaos to the centralised government of Franco and finally to the decentralised autonomous communities we have today. With the implementation of the Autonomous Communities, Spain went from being one of the most centralized countries in the world to being one of the most decentralized. Little wonder the event is celebrated in Andalucia.