Huelva is a port on the Atlantic coast of Andalucia, Spain. Known to the Tartessians, Phoenicians and Romans as an outlet for the metal ores from the Rio Tinto region

By Nick Nutter | Updated 21 Sep 2022 | Huelva | Cities |

Login to add to YOUR Favourites or Read Later

Rio Tinto - red like blood

At the confluence of the Rivers Odiel and Tinto, Huelva is first and foremost a port and it has been a port for over 3,000 years. When the Phoenicians arrived, about 1000 BC, they noticed two things. First the copper, rusty colour of the water entering the estuary from what is now the Rio Tinto; a sure sign that metallic minerals were present further upstream, and secondly the presence of a people, the Tartessians, who were already exploiting the metals. The Tartessians were the southernmost point of a network that went via Portugal and Brittany to Cornwall for tin, the metal that, when combined with copper, produces bronze. A hoard of bronze age swords found in the river at Huelva attests to the importance of this trade.

Muelle de Tinto

The Tartessians seemed to be willing to trade with the Phoenicians and eager to embrace eastern Mediterranean architecture, decorations, ceramics, glassware, style of dress and the Phoenician alphabet, with a few modifications that generated a language that is now recognised as uniquely Tartessian.

Huelva became an important trade centre for the Phoenicians who called the place Onoba and it may have been the location of Tartessus, the fabled, fabulously wealthy capital of the Tartessian tribe. Modern citizens are still called Onubenses in Spanish.

Bronze Swords Huelva Hoard

Refined metallic ores from the Rio Tinto region, initially copper and gold, were exported from Onuba to the emerging civilisations in the eastern Mediterranean along with cereals grown in the fertile Guadalquivir valley. In exchange, the Phoenicians introduced the grapevine to the area and wine was soon on its way east in the distinctive amphorae, along with olive oil. It is unclear at the moment whether the olive tree was brought to southern Spain from the Middle East during the Neolithic period or whether it was brought 5000 years later by the Phoenicians. The process of cupellation, a method of extracting silver from lead ores, had long been known in the Levant. The process was introduced to the Tartessians and small amounts of silver joined the list of exports. The Tartessians did not necessarily exclude other trading partners. A Corinthian helmet, found in the river in 1930, may indicate Greek traders or at least contact via other traders with Greece.<

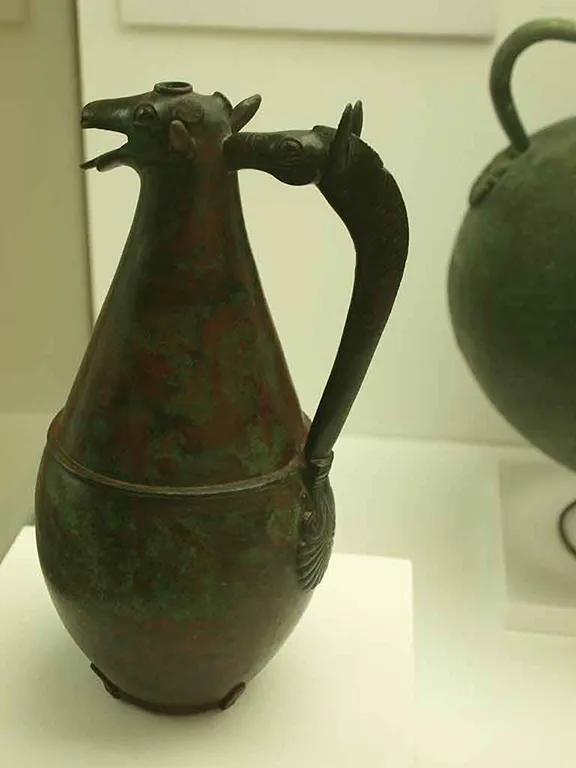

Turdetani Jug

Following the decline of Phoenician trade and the subsequent demise of the Tartessians in the 6th or 7th Century BC the area was taken over by the Turdetani tribe who held it when the Romans arrived. They issued silver coins, minted at Onoba that bore Iberian legends.

Human water wheel - Roman mining

The Romans called the town Onoba Aestuaria and continued to use the place as a port for the metals from Rio Tinto. In the 19th Century a large wooden wheel used by slaves in Roman times as part of the mine drainage system was excavated from a mine at Rio Tinto, then owned by the British Rio Tinto Company Ltd, and donated to the British Museum in 1889. It was returned to Huelva recently and now takes pride of place as you enter the Huelva Archaeological Museum. The influence of the British in the area can be clearly seen in an area of town known as Barrio Reina Victoria, Queen Victoria district where you will find very English style houses.

The connection between Huelva and the Rio Tinto mining area was to last 3000 years, to the modern-day. In 1876 a railway line was built by the Rio Tinto Company Ltd to take the ores directly to the ships moored at the quay in the Rio Odiel. It was last used in 1975. The trackbed, the Muelle del Tinto, was restored as a walkway in 2003 and is now a popular promenade for locals and visitors.

Christopher Columbus Statue Huelva

Just south of the city is Palos de la Frontera, a small port on the Rio Tinto. It was from here that Columbus set off on his first voyage of discovery. Columbus rates a few mentions in Huelva itself. The tourist board have produced a leaflet called Columbian Sites that takes you to places in or near Huelva connected in some way with Columbus.

The Fiestas Columbinas in Huelva is a week long celebration of Columbus and his discovery of the Americas, normally held at the end of July.

The British influence in the area even impacted on sport. Huelva’s football team, Recreativo, is the oldest in Spain and it was founded by the Brits. Alexander Mackay and Robert Russell Ross, workers at the Rio Tinto mine, founded Huelva Recreation Club in 1889 to provide their employees with physical recreation. The first interregional game of football was played in 1890, in Seville, against a team from the Seville Water Works. Only two members of either team were Spanish and they played on the Huelva side. The result, Seville won 2 – 0.

During the Second World War, Huelva was a centre of espionage. German agents monitored the movement of ships in and out of the Mediterranean and British agents were instrumental in Operation Mincemeat. The operation was a subterfuge to persuade the Germans that the imminent landings on the Mediterranean coast of occupied Europe were to take place in Greece and Sardinia rather than Sicily. A body carrying false information was allowed to wash ashore to be found by German agents. The misinformation carries on to this day. In the cemetery of Nuestro Senora is a headstone that reads,

‘William Martin, born 29 March 1907, died 24 April 1943, beloved son of John Glyndwyr and the late Antonia Martin of Cardiff, Wales, DULCE ET DECORUM EST PRO PATRIA MORI, R.I.P’. In 1998 the Commonwealth War Graves Commission added an inscription, ‘Glyndwr Michael served as Major William Martin.’

Huelva today is a modern city. During the earthquake of 1755 (known as the Lisbon earthquake) many buildings were damaged in Huelva so many of those you see today are late 18th, 19th and 20th Century, the later building financed by the mining boom of the 19th Century. The centre is a broad, tree-lined pedestrian area, very clean, with restaurants and bars beneath cloisters. The Tourist Information office in the central square, Plaza Las Monjas, is an excellent source of further information.